History teaches us about important lessons, people, and events. It shapes a nation. It tells us who we are and where we came from. It tells us about our past evils and also about our good deeds. As we conclude Black History Month, I want to tell you an important part of history, a movement that took place in Chicago, in our own backyard, but that gets neglected and lost in history. I want to tell you about a movement that inspired many people and changed a city forever: the Chicago Freedom Movement.

The Chicago Freedom Movement was a coalition led by radical Black organizers in the 1960s who raised awareness and pressured city officials to address racist housing discrimination. The seeds of why and how the movement came about can be traced back to the Great Migration, in which some seven million African-American people left the racist repression of the Jim Crow South to look for work and safety in northern cities, and its legacy is the creation of the Fair Housing Act.

More than half a million came to Chicago between 1916 and 1970. “Before this migration, African Americans constituted two percent of Chicago’s population; by 1970, they were thirty-three percent,” according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Yet Black people continued to face discrimination in the north, as Chicago was segregated along ethnic and racial lines. Irish, Polish, German, Italian, and Black people lived in their own segregated communities. At first there was discrimination against Irish, Polish, and Italian immigrants, but eventually, they were integrated into American society, accepted, and treated as equals.

Through policy and force, Black Americans were kept isolated and not allowed to live in large swaths of Chicago. The Chicago Freedom Movement Program would later state, “Racism, slums, and ghettos have been the essentials of [Black] existence in Chicago. While the city permitted its earlier ethnic groups to enter the mainstream of American life, it has locked [Black people] into the lower rungs of the social and economic ladder.”

For many years, U.S. cities relied on racial zoning ordinances that legally barred African-American residents from living in certain neighborhoods under the guise of “separate but equal.” But after these laws were struck down as unconstitutional in the 1917 Supreme Court case Buchanan vs. Warley, cities, homeowners, and developers began relying on other segregation tactics like restrictive covenants and redlining.

Racially restrictive covenants were agreements between property owners that they would keep the neighborhood white. If an owner decided to sell his property, they could not sell to Black Americans—only to white Americans. There were hundreds of covenants in neighborhoods across Chicago, in neighborhoods like South Shore, Hyde Park, and Humboldt Park. A 2001 article in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society found that in 1939, Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) vice-chairman Robert Taylor estimated that eighty percent of Chicago’s land area was covered by racial restrictive covenants.

Redlining was another tactic used, developed by Homer Hoyt, the chief economist for the Federal Housing Administration in the 1930s. With America in an economic depression, President Franklin Roosevelt wanted banks to give out low-interest loans to people so they could build homes and rejuvenate the economy. This policy of subsidizing homeownership helped the country emerge from the depression and create suburbs, mainly benefitting white Americans.

But these loans were not given out equally. Mortgage lenders and banks across the country designated some neighborhoods as desirable and safe for loans, and others as undesirable, commonly using a red color to outline these neighborhoods on maps. People living in so-called redlined neighborhoods, who were predominantly Black, were denied mortgages and loans. The practice allowed white people to build homes and create wealth while Black people were forced to keep renting in segregated communities. In 2017, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago concluded that redlining “had meaningful and lasting effects on the development of urban neighborhoods through reduced credit access and subsequent disinvestment.”

As a result of redlining and racially restrictive covenants, Chicago was one of the most segregated cities in America by the 1960s. In 1960, sixty-nine percent of the city’s 813,000 Black [people] lived in eleven of the city’s seventy-six community areas. These confined pockets where Black people could live became overpopulated and the quality of life and housing deteriorated over time. Many Black residents were forced to live in dingy, unsanitary apartments, which lacked heat and hot water, and were often rat-infested, according to a 2008 law review article.

Throughout the twentieth century, Black activists fought these practices and called for change. One such activist was Albert Raby. Al Raby was born in Chicago in 1933 into a poor family. He dropped out of school in eighth grade to support his family and became involved in union activity before joining the army. After coming back, he attended day and night school to earn his high school diploma, and then his teaching degree in 1960. He taught seventh grade at an all-Black school on the West Side and helped create the Teachers for Integrated Schools, a national network of educators and civil rights groups that was based in Chicago.

Raby was picked as the delegate to the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), which was an organization that wanted to end segregation in public schools across Chicago. In his role, he organized protests, marches, boycotts and was the spokesperson for the organization. By 1965, he knew that he needed help. To create real change, he needed to place national pressure on Chicago politicians. So he called upon Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to bring his Southern Christian Leadership Conference to Chicago and hold demonstrations like those held in Selma and Montgomery. In the South, the SCLC would host sit-ins, nonviolent protests, and marches to demand action from the federal government.

By January 1966, King and his family had moved to 1550 South Hamlin Avenue in North Lawndale. The SCLC and CCCO formed a coalition to bring awareness to housing segregation. This was the birth of the Chicago Freedom Movement, in which Raby played a crucial role. As the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who was involved in Operation Breadbasket, would later say that Raby’s contribution “was probably the single biggest reason that Dr. King came to Chicago [in 1966].”

King hoped that the SCLC could have the same success in Chicago as it did in Selma and Montgomery, which inspired the passage of the Voting Rights Act. He hoped Chicago could achieve a system of fair and open housing. King also wanted to use Chicago as a model for other cities. At a summit of community organizations in 1965, he said, “If we can break the system in Chicago, it can be broken in any place in the country.”

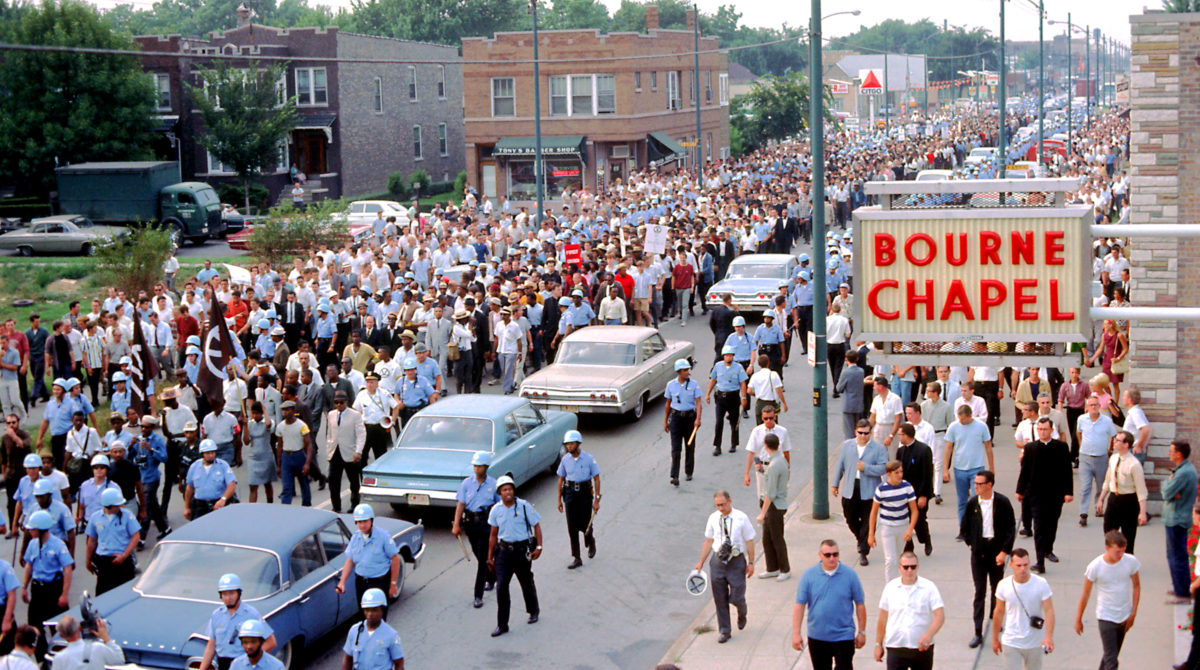

The movement started to gain traction across Chicago because of its demonstrations and marches that culminated in July 1966, with a march to Soldier Field. Around 30,000 people gathered to listen to King speak on housing discrimination and the “slums” that Black Chicagoans were left to live in. King proclaimed, “We are here today because we are tired. We are tired of paying more for less. We are tired of living in rat-infested slums…We are tired of having to pay a median rent of ninety-seven dollars a month in Lawndale for four rooms while whites living in South Deering pay seventy-three dollars a month for five rooms. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God’s children.”

After the speech, King led a march to City Hall. There he placed his demands on the door of the building, asking then-Mayor Richard J. Daley to make changes that would ensure fair and open housing to all Chicagoans, such as “Public statements that all [housing] listings will be available on a nondiscriminatory basis” and “Public statements of a nondiscriminatory mortgage policy so that loans will be available to any qualified borrower without regard to the racial composition of the area.”

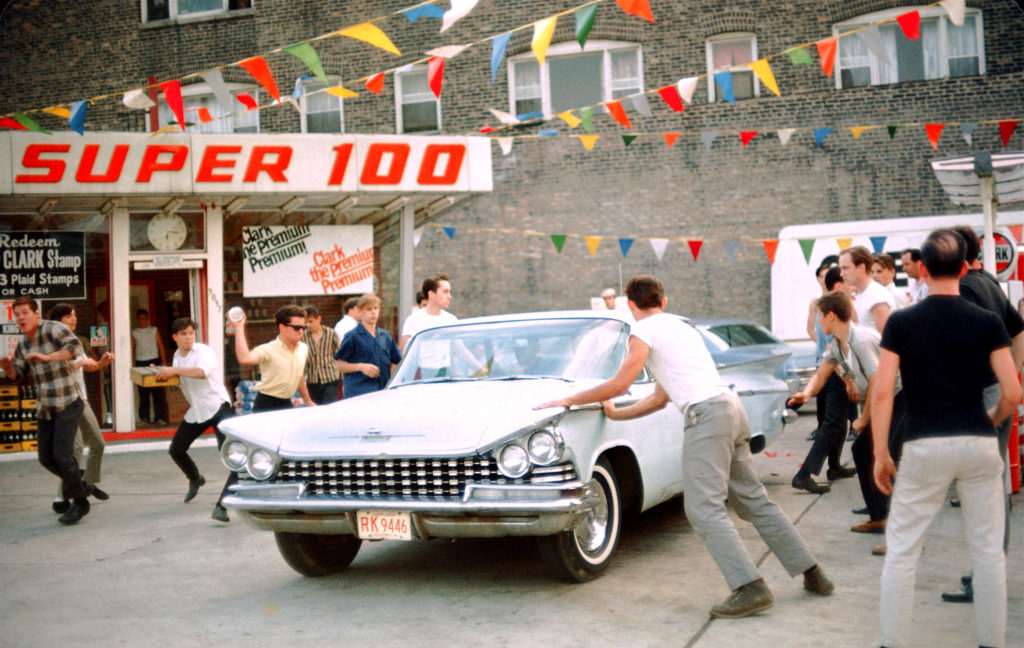

The movement energized Chicagoans to march in the streets demanding change and equality, but it also inspired counter-protests from those who did not want an integrated city. They attacked marchers led by King by throwing bricks, bottles, and rocks at marchers while screaming racist profanity and waving Nazi and Confederate flags. King was disappointed but not deterred. He was going to continue calling for change using non-violent demonstrations.

Daley faced pressure from King, who threatened to take demonstrations across white neighborhoods in Chicago if something was not done. Not wanting his city engulfed with violence, he agreed to host a summit with King, the CHA, and other business leaders. An agreement was reached on August 26, 1966, when the CHA promised to build public housing and the Mortgage Banks Association promised to not partake in redlining and denying loans on the basis of race. King knew it was going to be an uphill battle and this was only the “first step.”

After the agreement, the movement started to fizzle out. Raby decided to go back to school and study history at the University of Chicago. By January 1967, King had left Chicago to continue his efforts in other parts of the country.

The city continued to be segregated and Black Chicagoans still faced housing discrimination despite the promises made. Because of this, some critics believed the movement was a failure. Others counter that it was not a failure, because it inspired the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. “If out of [the Chicago Freedom Movement] came a fair housing bill, just as we got a public accommodations bill out of Birmingham and a right to vote out of Selma, the Chicago movement was a success, and a documented success,” said Jackson.

The act was a step toward fair and open housing across American cities. The Housing and Urban Development Department explains that the Fair Housing Act protects people from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home, getting a mortgage, seeking housing assistance, or engaging in other housing-related activities. The FHA provided people with a legal roadmap to fighting housing discrimination through the courts by instituting fines and other consequences for discriminatory practices.

Chicago, and cities across the country, continue to be segregated. Black Chicagoans still face discrimination when seeking mortgages and many struggle with high rents, evictions, and poor housing conditions. As today’s activists seek to tackle these issues, we’d do well to see these fights as a continuation of the efforts of groups like the Chicago Freedom Movement and organizers like Raby and King.

Igli Velcani is a second-year law student at UIC Law and a student attorney at the Fair Housing Legal Clinic. He was born in Albania and immigrated to the United States in 2000. He grew up in Mount Prospect. This is his first piece for the Weekly.