The Parents

A conversation with Saeri Geller & Brent Warren

Saeri Geller and Brent Warren’s son Ian was fifteen months old when his doctor found that he had high blood lead levels. Since then, Ian has gone through two rounds of drug therapy and his parents are working to clear their house of lead.

Geller: In November 2015, we moved into my husband’s grandmother’s house in Park Manor. I got a home lead test and I tried testing the windows and they came back negative. But they only test the top layer of paint, and I didn’t really test where it was chipping because I didn’t know if it would work properly on chipping paint.

When my son, Ian, was nine months old, the doctor did a blood lead test and they told me it was normal. I found out later that it was four micrograms per deciliter and I was really upset. The city deems a zero-to-four blood lead level as normal, which it shouldn’t, because there’s no safe lead level in children. And they don’t tell parents that.

Shortly before his fifteen-month appointment, I saw him putting paint chips in his mouth. I requested another blood lead test from the doctor and that’s when it came back elevated, at sixty-three micrograms per deciliter. We went to the emergency room and stayed overnight, and they gave him chelation therapy. They discharged us with the medication and that was the start of our adventure. The first round of medication was two and half weeks long, and the second was twenty-eight days.

Warren: In the meantime, we’ve been trying to make sure our house is safe, which has been a huge challenge. The government sent a housing inspector out, who said we would get the results back in a few weeks. We asked him to come back to test the water, but he wound up giving my mom the paperwork that stated all this work needs to be done by October 10 or else the city could take us court. But that was never explained to us.

So we’re here waiting for the city to get back to us, spinning our wheels and wasting time and money, because Saeri and Ian are living elsewhere. In the meantime, the inspector passed away and we couldn’t get a hold of anyone from his department.

The Tuesday after Columbus Day, his supervisors told us that our case has gone to court because we hadn’t completed the work on time. We still haven’t gotten a court date, but the work is in progress as of the beginning of December and we hope to be all living under one roof again as a family by the holidays.

Geller: This isn’t really something that you put behind you. And it’s not something that you can really forget about, because the lead isn’t really gone from the house. It’s painted over. It’s there, it’s around us.

My message to other parents is to educate yourselves. Be aware of what chipping lead paint looks like. Get your houses tested; it’s worth the money. I’ve been out of my house for four months now and it’s been awful. I’ve been so blessed and lucky to have friends and family who will support me and take me in, but not everyone does.

The Student

A conversation with Maya Orr

Maya, 14, is a freshman at Foundations College Prep in Roseland. Foundations is a charter school, so Chicago Public Schools did not test its water for lead. But Maya and her fellow students tested the water at school and at their homes as part of a community service project when she was in eighth grade.

The first time I heard about lead was from my parents. My cousin ate some paint with lead in it when he was four years old, and we think he got autism from it. He’s 12 now and he’s smart and all, but he can lose his temper. Sometimes he just zones out. And he doesn’t know how to read.

Having a cousin that grew up with lead poisoning made a big impression on me. I didn’t even know that something could be dangerous in paint until my parents told me about what happened to him.

The first I heard about lead in water was from my community service teacher last year in eighth grade. After what happened in Flint, Michigan, our class started talking about it. Our teacher told us that since you don’t know if lead is in your water, you have to be careful. I was scared, because you could be drinking a whole bunch of water and there might be lead in it.

Our teacher gave us two containers each to take and test the water in our homes. We had to make sure nobody used the water before us in the morning and then put the water straight into the containers.

I wasn’t sure if our water was going to have lead in it. I thought maybe it would, because when the city people were working on our block’s pipes, I turned the water on and a whole bunch of dirt came out. The city said you have to run your water for a long time so all the dirt and stuff will come out.

I don’t remember the exact number that our water came back at, but thankfully it was safe. The school also didn’t have lead. Now when I go to school, I feel safe because it’s been tested. Our teacher told us that we need to use less faucet water. I drink bottles of water now, because they go through a filtering machine. And if I do drink faucet water, I use the filter hooked up to my sink at home.

At the park, I don’t like drinking out of a fountain because people are putting their mouths on the faucet and there are germs. But then you never know if there is lead there, too.

I think people should check and see if they’re safe or not, especially if you have kids. My cousin was little when he ate the paint. Kids don’t know what they’re doing. I think if you have a baby on the way or you have kids in the house, it should be safe for them.

The Fighter

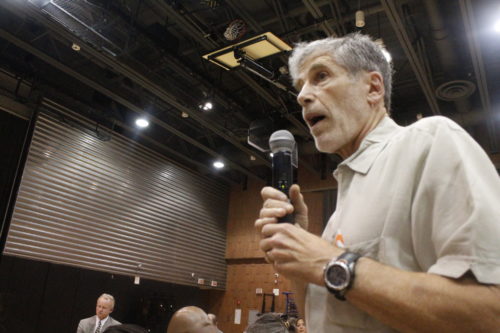

A conversation with Howard Ehrman

Dr. Howard Ehrman served as the director of primary care and assistant commissioner in the Chicago Department of Public Health from 1985 to 1991 and has taught public health and medicine at the University of Southern California, Cook County Hospital, and University of Illinois at Chicago. He is now retired and a full-time environmental justice organizer.

I’m a native-born Chicagoan. I grew up on the South Side until I went to high school, and I have lived in the city of Chicago probably fifty-five years of my sixty-nine years of life. I love Chicago. I love the people.

I started working on lead as an intern in the summer of 1968 with Dr. Henrietta Sachs at the Chicago Department of Public Health. People organized to put pressure on Mayor Richard J. Daley and the health department to fix the lead problem, especially people in Englewood and Pilsen. These were civil rights groups including Al Raby and a lot of community organizations and churches.

Children were dying regularly of lead poisoning in the 1960s, mostly black and brown kids who were poor. I worked with the city’s “lead mobile,” going door to door and putting the van in different places like churches and schools so kids could get tested.

Then in the late 1980s, a lot of white, middle- and upper-class parents, started buying older homes and renovating them by scraping or burning off paint while their kids were in the home. So there were a number of kids like that who got lead poisoning.

At that point President [George H.W.] Bush worked with the Congress to get more funding for lead poisoning, which was a good thing. So lead poisoning programs expanded and the blood lead level the government considered “normal” came down from forty to twenty-five to fifteen, to now, it’s five micrograms per deciliter.

It’s good that we’ve made real progress in terms of the number of kids who are lead poisoned. But the problem is that over the last fifteen years, the number of kids who have been poisoned hasn’t gone down. Almost all the lead poisoned kids now are poor kids that are black or brown or Native American. In the last fifteen years the federal state and local governments have actually significantly cut back on lead poisoning programs. During the Obama administration, the National Lead Prevention Task Force was eliminated. Chicago has significantly cut the lead budget for home lead inspectors, lead testing of children, and more.

The city must expand its lead program and force landlords to clean up lead-contaminated properties. The city must begin a program in 2017 to replace all water lead service pipes.

And organizations new and old like Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project, and the NAACP must once again organize to make this tragedy an issue that we will all work on together.

We’ve had a situation that was never that good go to very bad. And we have a cohort of kids with lead poisoning not making progress because we’re not doing what we need to do. We lack funds, lack people, and most of all we lack the political will to do it. So until this isn’t a problem anymore, I’ll be working on it.

This story was produced in partnership with City Bureau, a Chicago-based journalism lab.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.