Some Chicagoans still remember the record-breaking blizzard of 1967. Public transportation halted, power was out across the city and people had to dig their vehicles out from under twenty-three inches of snow. Even O’Hare International Airport—at the time the busiest in the world—shut down for two days.

Chicagoans emptied supermarket shelves citywide, and in some parts of the city residents reportedly broke into stores. Sixty deaths were attributed to the snowstorm. At least one of them, ten-year-old Delores Miller, was killed by a member of the Chicago Police Department.

News reports accepted the police account that Delores was killed in a “shootout” with “looters,” implicating the ten-year-old by association. Of the seven news articles that mentioned Delores, all of them called her a “looter” or emphasized that she was with a group that was looting when she was killed. One Tribune article, titled “Police, Firemen Find Hard Jobs Harder,” was openly sympathetic to the police for having the difficult job of policing during a blizzard. The article, which relied solely on police sources, did not name Delores or say how old she was, and reported that police said she was “among the looters.” None of the articles about her death talked to Delores’s family or friends.

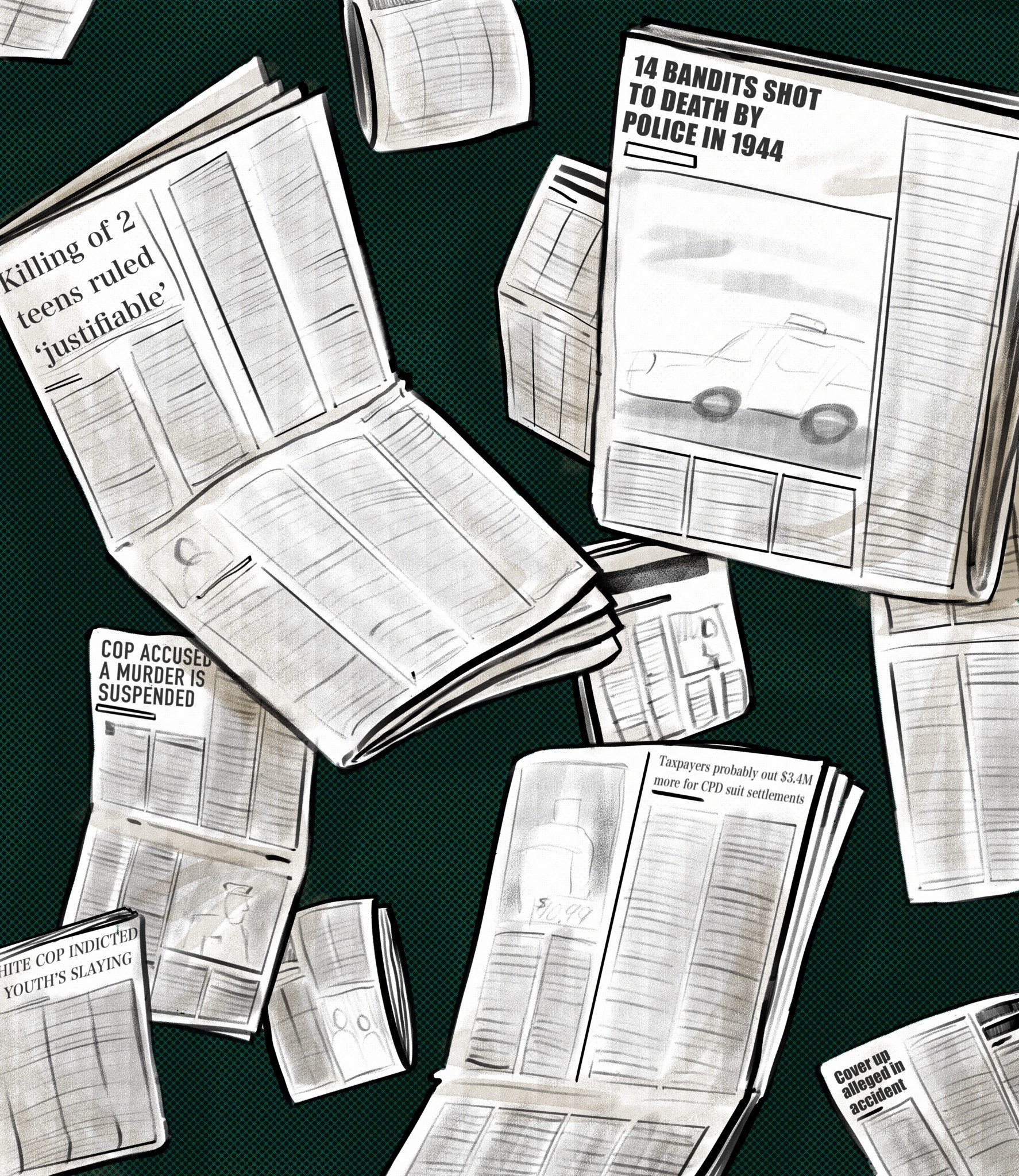

Newspaper coverage has relied heavily on department accounts of police killings at least since 1945, when James Gavin, police reporter for the Chicago Daily Tribune, wrote a breathless roundup of the fourteen “bandits and burglars” killed by CPD “protectors and defenders of the home front” in 1944—a year that saw the Chicago police kill two children under eighteen.

CPD has a long history of killing children. From 2013 to today, Chicago police officers have killed more people under the age of eighteen than any law enforcement agency in the United States, according to data from Mapping Police Violence, a research group collecting comprehensive data on police killings nationwide. The CPD’s grim total is greater than those of the next two police departments combined—the Columbus, Ohio PD, where a police officer shot and killed sixteen-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant on April 20, and the New York City PD.

In the wake of thirteen-year-old Adam Toledo’s March 29 death in Little Village, the Weekly analyzed eight decades of children dying in encounters with Chicago police. We compiled the data for that analysis from local newspapers and the Fatal Encounters database, a continuously updated record of all U.S. deaths resulting from interactions with the police since January 1, 2010.

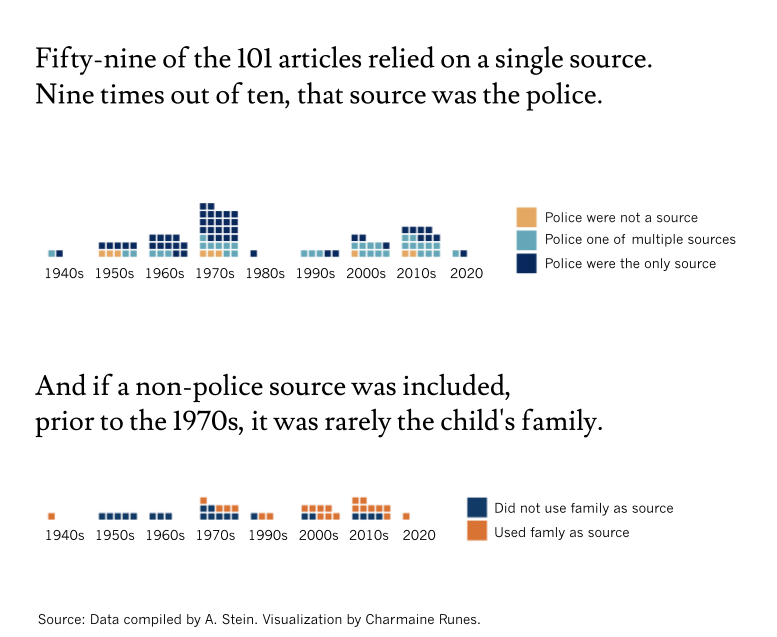

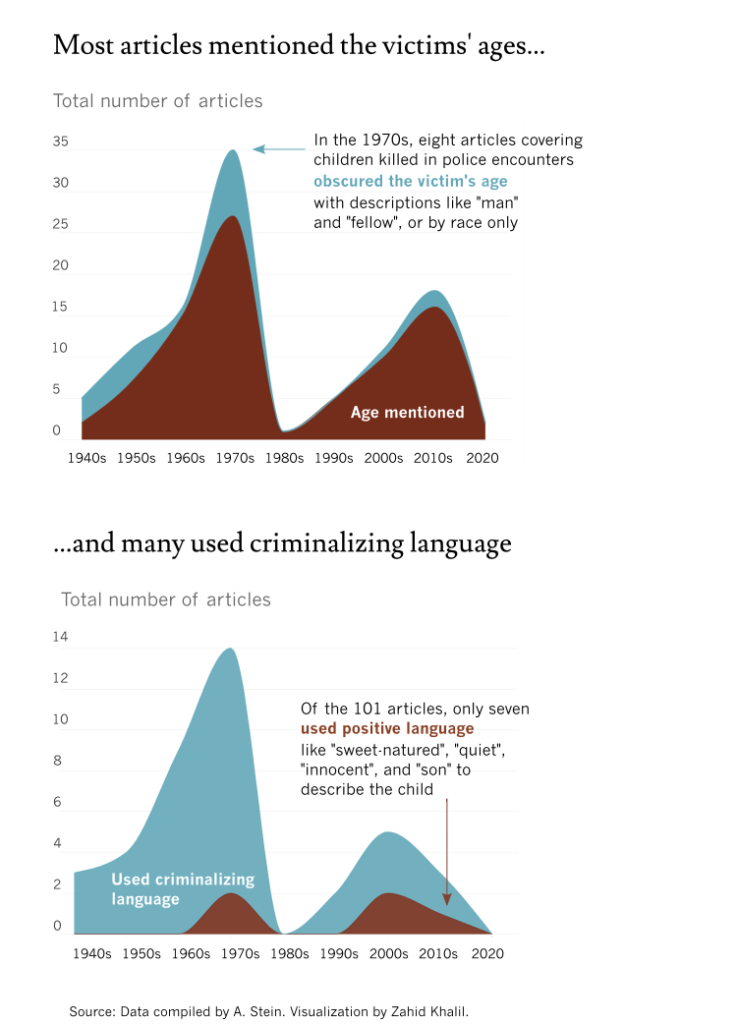

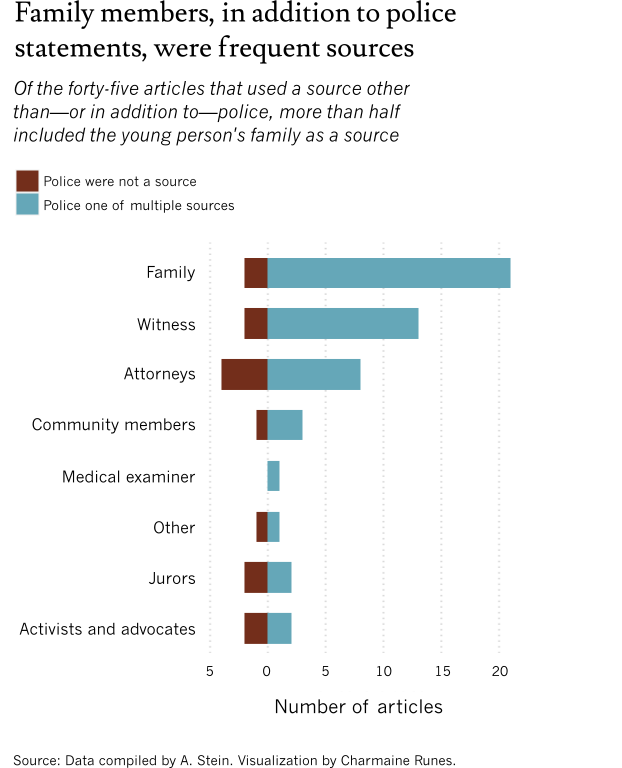

Next, we reviewed 101 newspaper articles about those deaths to see how the media’s portrayal of the victims changed over time. We analyzed the adjectives used to describe the children, the number of articles citing police or other sources when discussing the incident and people involved, and whether the media narrative describing the murder changed as new evidence emerged after initial reports. Of the 101 articles we included, police were cited as a source in eighty-eight, and victims’’ families were sources in twenty-three.

Fifty-nine articles included only one source, and nine times out of ten that source was the police. Of the articles that did include the young person’s family as a source, only two did not also report the police’s narrative. For more than half of the victims, the first article about the killing used only the police as a source, even if the media eventually incorporated other sources in later articles.

As video footage has repeatedly contradicted official police accounts of recent killings, the press has begun to question the reliability of police narratives in cities across the nation. Chicago is no exception. Last month, CPD reported that Toledo was killed during an “armed confrontation” with police. Officials including Mayor Lightfoot and an Assistant State’s Attorney repeated that narrative to the press for two weeks before the Civilian Office of Police Accountability released body-worn camera footage showing the officer shot the thirteen-year-old while he had his arms raised above his head—no weapon in hand.

The case of Adam Toledo is only the latest in which incident reports and public statements from CPD have later proven to be incorrect or false. When then-police officer Jason Van Dyke killed sixteen-year-old Laquan McDonald in 2014, police said he was behaving erratically and “lunged” at officers with a knife. Thirteen months later, when dashcam footage from responding police vehicles was released, that account was disproven.

For decades, Chicago newspapers have relied on CPD as either the primary or sole source of information about the circumstances surrounding the deaths of children in encounters with police. In the articles the Weekly reviewed, police were the sole source of information more than half the time from the 1940s through the 1980s. While the percentage of articles citing police remained relatively constant over time—at or near ninety percent—after 1990, newspaper reports became six times more likely to include a member of the victim’s family as a source than in previous decades. Despite that, local media still rely heavily on police reports when reporting on crime as well as deaths at the hands of the CPD.

The 101 newspaper reports the Weekly reviewed noted the victims’ youth eighty-two percent of the time. Nineteen articles omitted references to the child’s youth or inflated their maturity with descriptors like man or fellow. Twenty-one articles painted the dead child as a criminal with adjectives such as runaway, dropout, suspect, or attacker, or linked them to crime, as in articles describing Dolores Miller as a looter, or Adam Toledo, who police and news reports hinted at being associated with a gang. For victims’ families, such characterizations can be as frustrating as they are heartbreaking.

The media “definitely demonizes your child,” said Gloria Pinex, whose son Darius was killed by CPD during a traffic stop in 2011. “They make it seem like they was the one that was in the wrong. It’s sad.”

Darius was twenty-seven when the police killed him, but to Gloria, he is still her “baby.” When Gloria went to the crime scene after her son was shot, police refused to talk to her or give her any information. But when a news anchor from WGN-9 approached police, she had a story instantly.

Initial news reports repeated police claims that Pinex, who was Black, was fleeing from officers and refused to pull over. But police video footage that was hidden from the Independent Police Review Authority (COPA’s predecessor agency) for five and a half years showed otherwise: Pinex pulled over within seconds of officers turning their lights on.

Gloria held her own press conferences, protested with other moms who lost children to CPD, and did everything she could to tell her son’s story, but she said the media focused on his number of prior arrests and repeated characterizations, such as “reckless driver,” from the police reports. Even when reporters did interview her, Gloria felt they turned her words around.

“It’s hard to maintain a regular life and to deal with, the way I feel it, a whole other game, because I was ganged up on to make a story fly,” Gloria said.

In September 2020, the Weekly spoke to Erik Vega, whose older brother Miguel was killed by CPD that August. He too expressed disappointment with media portrayals of Miguel as belonging to a gang.

Arionne Nettles, a journalist and professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, recently wrote about this persistent narrative of “victim wrongdoing” common in major media publications.

“A police officer or wannabe vigilante kills a Black or Brown child, major media publications look for victim wrongdoing, and a debate ensues as the journalists who write about said wrongdoing argue that digging into the lives of these victims is warranted, a way to tell ‘both sides,’ ” she wrote.

Speaking to the Weekly, Nettles explained that people are often unaware of the biases they carry when reporting. Those biases extend beyond race to where reporters live in the city and their understanding of the dynamics in different neighborhoods.

But whether intentional or not, she explains that it’s paramount to understand how reporting on victims of police violence holds the potential to harm communities and families.

“It’s really about how can we all work together to better serve the audiences we have signed on to serve,” Nettles said. “If people are so hurt by the work that we do that they stop listening, stop reading it doesn’t help our cause. It doesn’t help all the hard work we’re doing.”

Nettles noted that there are newsrooms and journalists in Chicago who have been working diligently to change and build relationships with communities that have historically been disregarded. But she said it’s going to be a team effort in order to remediate harm and do better going forward.

“It’s never just one story, one article, one journalist. If we can’t hold each other accountable as peers and colleagues, then nobody else can.”

If you are interested in engaging in conversations about media coverage of police and police violence, both the civic journalism lab City Bureau (citybureau.org) and the Chicago Headline Club (headlineclub.org) are hosting online panels on the topic on Thursday, April 29.

Madison Muller is a graduate student of social justice journalism at Northwestern University. She last reported on disparities in media coverage of mass shootings. Alex Stein is a lawyer and researcher who lives in Chicago. He last reported on forty children who died in police encounters since 1944. Ed Vogel lives in Back of the Yards. This is his first piece for the Weekly.

Really thoughtfully written. Thank you. ????