Turning onto 47th street from the Dan Ryan, Kate Zanetti feels like she is entering a haze of dust and emissions as she commutes to her job at Back of the Yards College Prep. As she passes truckyards, stockyards, and factories, she watches her students walk to school through heavy thickets of dust kicked up by the large trucks that cruise by. These particles will inevitably enter their small respiratory systems as they inhale and exhale on their way to class.

“When I first started working here, I was shocked at how many students had asthma until I really sat down and realized that it is extremely likely [their conditions were] due to the air pollution in the area they grew up in,” Zanetti said. “It frustrates me because this environmental injustice was most likely the cause for my kids having lifelong ailments. The City officials continue to disparage certain communities.”

A new environmental justice tool aims to equip community members, organizers, and policymakers to combat these disparities.

The Midwest Comprehensive Visualization Dashboards (MCVD) is a series of interactive maps that show emissions burdens for Chicago Public Schools (CPS) students. The three-part preliminary study—conducted by the UIC School of Public Health (UIC-SPH) Emergency Management and Resiliency Planning (EMRP) program—found environmental hazards in Chicagoland are more likely to be concentrated in neighborhoods with CPS schools containing higher Latinx enrollment.

The study, which aims to give community members access to data to educate others and substantiate their own environmental justice claims, was initially created four years ago when a group of grassroots organizations and local residents from the Southwest Side approached the UIC researchers in search of a way to bring issues of environmental justice to light. Specifically, they were concerned with the development of a potentially hazardous asphalt plant in McKinley Park, MAT Asphalt.

Adopting a community-based participatory design (CBPD), the researchers implemented an input approach to engage local stakeholders. During this time frame, they collaborated with the Southwest Environmental Alliance (SEA) to hold focus group meetings and organize presentations with various policy decision-making entities, including 25th Ward stakeholders, the Latino Caucus of Chicago, the Committee on Environmental Protection & Energy, and the larger City Council.

“This is a grassroots movement. These are just regular people working amazingly,” said UIC-SPH-EMRP researcher Michael Cailas. “[They organized] two meetings with the U.S. EPA Region Five director—that doesn’t happen. So it’s because of them that the official agencies’ servers are responding.”

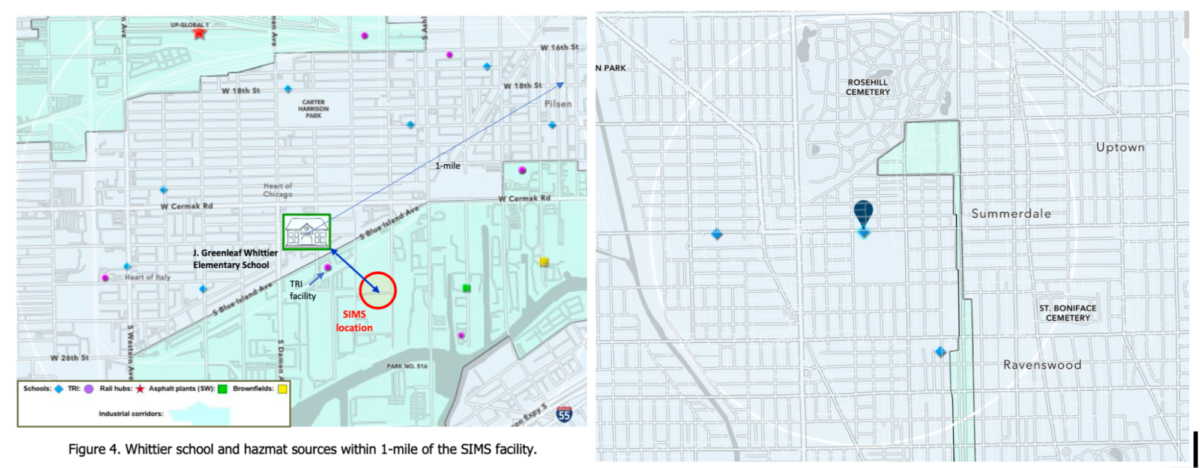

The result of these talks was the creation of an interactive electronic story map that shows the distribution of select hazard sources deemed to pose a threat to Chicago communities, including toxic release inventory (TRI) facilities, rail hubs, asphalt plants, and brownfields, which are properties “the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant,” according to the EPA.

Users can input a specific address and set the proximity radius from 0.5 to 2 km to determine the quantity and type of hazards near their location of interest, including Chicago Public Schools. The map shows many of these industrial sites clustered near schools in Back of the Yards and La Villita.

Cailas said it was important to focus on schools mainly due to the duration of exposure. It is important to note that hazards (things that can cause harm) are not synonymous with risk (the likelihood that a hazard will cause harm). Their research does not attempt to find a direct link between hazards and health outcomes, he said; their study only makes claims about people’s exposure to hazards.

“You have environmental contamination in the area where they live and where they’re walking to and from and where they’re spending half their week,” said UIC researcher Apostolis Sambanis. “And so there’s this contamination and potential that they can be exposed to, [which] needs to be considered.”

While this study does not have any bearings on health outcomes, its importance lies in its ability to visualize the effect of cumulative hazardous emissions from multiple potential sources in the same area. When granting permits to potential facilities, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) and City of Chicago only take into account the risk of that singular facility to the nearby community—they do not not consider the cumulative impact of many facilities within close proximity to one another.

The researchers behind the MCVD are hoping it will be used as a tool for community members and organizers to document their status in terms of environmental pollutants, identify community health disparities, and validate their environmental justice claims. Though this is only a decision support tool, said Cailas, the map can be instrumentalized to help policymakers with influence make more informed decisions on issues relating to sustainable urban development and the environment.

“We’re trying to give [community members] a voice to articulate themselves,” said Sambanis. “When they originally approached us, it was one asphalt plant [permit] that they were concerned about, whereas this now gives them the 30,000 foot overview of the bigger picture, and that’s what we’re trying to have them see.”

In recent years, Southsiders have united to battle myriad environmental injustices. They organized to fight against the demolition of the Hilco smokestacks; protested against the permit that would grant access to Sims Metal Management to operate in the area; pushed back against the shady establishment of the MAT Asphalt plant; and most recently, won against General Iron to deny the permit that would have allowed the company to relocate their scrap metal facility to the South Side.

Using this tool, community organizers and activists will have more visible evidence to tackle issues of climate justice and address the larger problem of structural discrimination in Chicago.

Sacrifice zones” refer to land, air, water, and soil that have been compromised by heavy polluting industries, who thrive economically—but at the cost of low-income people of color, said Citlalli Trujillo, a member of the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization (PERRO).

Environmental climate justice is about informing the community about the injustices by bringing them to the forefront, she said on an Earth Month Celebration panel presented by the UIC Latino Cultural Center on April 21.

Recently, many Chicago-based activists have spoken up to do just this.

Theresa McNamara has been involved in community organizing for most of her life. As a child growing up in Pilsen, she followed her mother and sister, who participated in creating Fiesta del Sol and later, were active in the 1974 construction of what is now Benito Juarez High School. Since then, she and her family moved to McKinley Park, where she first heard about MAT Asphalt coming to the community. Not knowing anything about the environment, she sought out to learn more.

When her husband came back from work one day, they began knocking on all the doors on their block. Of the ten doors that opened, McNamara was shocked to hear that eight of them housed people that had some form of cancer.

“That was totally eye-opening, because you see your neighbors every morning while you’re going to your car and you just say ‘Hello,’ you never say ‘Hey, what’s your sickness? What do you have?’” she said.

After asking if they would talk further, seven of her neighbors reconvened at McNamara’s home to discuss their issues. In private, one neighbor shared that she had taken her daughter to the hospital a year and half prior for a brain damage operation. The neighbor said that while she was there, she had met another person on their block, whose child was getting a shunt implanted for an upper respiratory condition related to cancer. At that moment, McNamara recalled the neighbor’s daughter came running to the door with a baseball cap on and a cotton ball on the inside, covering up the indentation on her skull.

McNamara decided to take issues into her own hands and arranged a group meeting with 12th Ward Alderperson George Cardenas, who assured them that they were installing two air monitors, one on Ashland Avenue and one on Western Avenue. At the meeting, one woman shared how every morning, when she would go to her backyard to drink her cup of coffee, she would have to clear off her table and chair because it was covered with dust.

“It started me thinking there has to be a bigger picture. And as I started pulling back the map of McKinley Park, I realized that we are surrounded by industrial corridors,” she said. “And so I even went so far as taking people into MAT Asphalt as [a] tour guide; I wanted them to see, because how can you fight something you don’t know nothing about?”

Normally, an asphalt company has to go through a formal process to notify their neighbors and send out letters to the community alerting them of their presence. However, McNamara noticed that MAT had done this all in a suspicious three weeks. When she called Mayor Lori Lightfoot—who had run on a platform of supporting the Latinx community and had personally told McNamara she was going to restart the environmental committee—Lightfoot ignored the calls.

Frustrated, McNamara started a petition in 2020 and began organizing regular meetings with neighbors and community members to inform them of pertinent environmental issues. Thus, SEA was born to fight environmental racism through direct action. Currently, it’s working with UIC and the EPA to distribute air quality monitors to Bridgeport and Brighton Park. They also collaborated with UIC on the MCVD study in the CBPD phase.

While McNamara is fortunate enough in her daily life to afford an air filter and a water filter to prevent lead exposure, she recognizes that not everyone can do the same.

With lead still in the pipes and MAT Asphalt bringing in 200 trucks a day—despite the hundreds of complaints about it that have been filed with the IEPA and the City’s health department—McNamara continues to call for justice and encourages her community to do the same.

Mather High School student Gianna Guiffra is from the Chicago Lawn neighborhood and started noticing how certain areas of Chicago were being polluted more than others. In her sophomore year, she got involved with the Sunrise Movement to uplift her beloved neighborhood and help enact green policies.

“It just makes me upset that our City isn’t really prioritizing the health of our community and the environment,” she said. “Instead, they’re continuously polluting our neighborhoods, [despite] increasing climate change. But knowing this, it motivates you to get involved and see what we can do as a city—either in CPS or in our neighborhoods—to allow our community to breathe cleaner air.”

Since joining the Chicago Hub of the Sunrise Movement, Guiffra worked to engage more youth by recruiting highschoolers for a Chicago Climate Summit that took place on Earth Day.

In the future, the young activist hopes to get more neighbors and CPS students involved with environmental curriculums. She also continues to fight for greater regulations on polluting companies as well as the creation of more green jobs to provide renewable energy to the city.

Though issues of environmental justice affect people of all ages, one population is especially vulnerable: children. Kindergartners through eighth graders are especially susceptible to the negative effects of pollution.

According to a 2018 World Health Organization report, “air pollution can impact neurodevelopment and cognitive ability and can trigger asthma and childhood cancer,” and children are especially vulnerable because they breathe more rapidly than adults and live closer to the ground where some pollutants are most concentrated.

In addition to disrupting brain development, environmental hazards can affect students’ academic performance. A 2016 study found that children in Florida who were conceived within two miles of a toxic waste site were 7.4 percentage points more likely to repeat a grade and 6.6 percentage points more likely to have a disciplinary infraction, versus a sibling who had been born once the site was cleaned. Black and low-income children in this study were more likely to be exposed.

2019 research by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) also revealed when students attend schools with higher levels of traffic pollution, they tend to show declining test scores, more behavioral incidences, and increased absenteeism.

“Here on the South Side, you see [kids] sitting there playing with something, and you take a closer look, it’s actually their inhaler that they’re playing with,” said McNamara. “You’ll see their mom say ‘put it in your pocket,’ but the shame of it all is to see so many of them. And it’s because of the neglect of the City and the government [for] dropping all these companies here in one area,” she said.

Founding member of Neighbors for Environmental Justice (N4EJ) Anthony Moser has been using public records to monitor air quality in Chicago for years, paying special attention to the health impacts on youth.

“[Air pollution] is a magnifier for COVID; it both increases the risk of getting it and also the risk that if you do get it, it will be more severe,” he said.

One study linked the impact of air pollution on mental health. According to the review, an increase of ten micrograms per cubic meter in the level of particulate matter was correlated to a ten percent higher risk of getting depression.

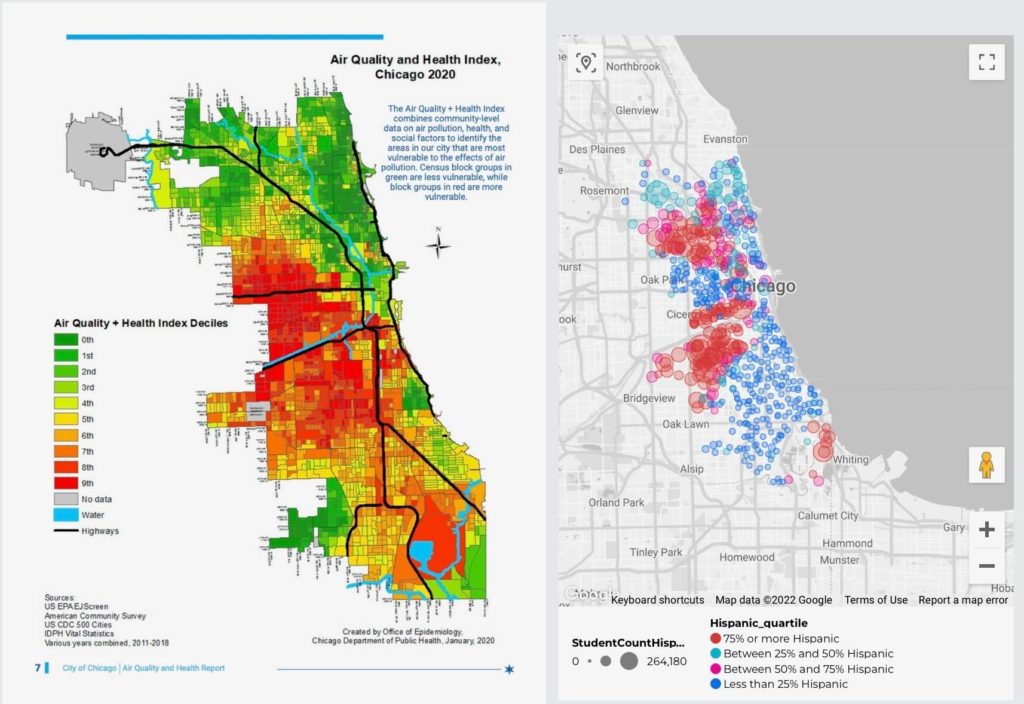

To demonstrate the disparity in who experiences poor air quality, Moser created a data visualization map that compares air quality to where CPS schools are located. Users can filter the schools by various demographic ranges to observe who is most at risk. The map helps to show how issues of environmental justice stem from systemic, citywide segregation and racist zoning practices that situate industrial facilities and polluters in neighborhoods with more Black, Brown, and low-income people who don’t speak English, said Moser.

“It makes me angry, but it’s also completely unsurprising. They say that every map of Chicago is a map of segregation. These are long standing patterns [where] the City chooses to put these kinds of facilities in these places, right. And MAT Asphalt is a great example of it. When you consider that they’re running essentially on City contracts, it’s not just that they’re being approved–the City is actively funding this,” said Moser.

Though there are regulations in place to protect children, schools have not been heavily regulated. The 1997 Executive Order (EO) 13045 calls for federal agencies to prioritize mitigating environmental health risks that disproportionately affect children. The EO also led to the creation of the Office of Children’s Health Protection (OCHP) to ensure EPA actions address children’s unique vulnerabilities.

And yet environmental hazards have existed within CPS for years and remain a large concern for the Chicago Teachers’ Union (CTU).

Science teacher at Northside College Prep and doctoral student at UIC College of Education Ayesha Qazi-Lampert has been a member of the CTU Climate Justice Committee for nearly two years. With the help of the committee and CTU education policy researcher Sarah Rothschild, the group used CPS’s 2020 school facility assessment reports to compile data on asbestos, lead, and air quality from eight schools, including George Washington High School, George Washington Elementary School, Chopin Elementary, Lincoln Park High School, Bridge Elementary, Barton Elementary, and Harlan High School.

According to their findings, CPS’s reports show myriad areas of concern. For example, there was asbestos material in 224 areas of George Washington High School, and the school’s ventilation system was over sixty years old. In Barton, there was water damage and cracks within the plaster walls and ceilings and thirty rooms did not have functional windows. In Harlan, the main electrical service of fifty years was “substantially corroded” and they found unsafe levels of lead in the faucets—as deemed by the CDC—with the greatest amount of 103 parts per billion of lead in the drinking fountain in the girls’ gym.

Furthermore, CPS’s air quality tests were conducted in empty rooms, which is against industry standard since the test must evaluate the level of carbon dioxide and total air exchanges per hour. Thus, the group concluded that community members cannot trust CPS’s air quality assessment, which deemed the schools safe for occupancy.

CTU Director of Communications Chris Geovanis believes that a substantial part of the problem when it comes to understanding what the conditions are truly like in school is CPS’s inability to make the information available.

“They have really fallen down on the job in terms of producing the kind of state mandated regular facilities updates and reviews. It’s just been an area of chronic neglect for decades. They have a $2 billion backlog, and they need to do better,” said Geovanis.

These health hazards are amplified when looking at the surrounding environments of schools on the North Side versus the South Side.

The MCVD study reveals that children on the South and West Sides of Chicago face greater exposure to environmental hazards.

“The issue is not a specific facility; the issue is how the facilities are distributed within the city. This is the core of the distributive environmental justice principle,” said Cailas.

According to data from the 2016-2017 Chicago Public Schools Database, Whittier had 299 students enrolled, 92.1 percent of whom were low-income and 99.1 percent of whom were Latinx.

Another stark example of this disparity is seen in Back of the Yards College Preparatory High School (BOYCP), which is located in an area that scored sixteen times above the city average for its proximity to toxic facilities. According to the map, the school is situated within a one-mile radius of a brownfield, asphalt plant, and ten TRIs emitting various chemicals: trimethylbenzene, toluene, zinc fume and dust, glycol ethers, lead, xylene, and hydrochloric acid. Within the same bubble, there are also four other schools that are affected by the same pollutants.

Zanetti has been teaching physics, biology, and anatomy and physiology at BOYCP for three years. In their last unit, she had her junior and senior anatomy students explore the respiratory system by completing a lab that mimicked respiratory distress. At this time, students who had respiratory disorders, mostly asthma, shared their own experiences of what distress felt like to them.

The class then observed the air quality index both seasonally and over longer periods of time in Chicago in order to make claims about how the quality of air affects respiratory function. All of the students brought up the facilities as well as the large trucks and eighteen-wheelers that constantly go up and down 47th street, said Zanetti.

“I did this mini project so they could not only see the effects of this pollution on their own individual health but also so students could question why this is happening so abundantly in their neighborhood, but not all neighborhoods,” said Zanetti. “I wanted students to see the environmental injustice, want to stand up for their community, and provide push back to City officials, because this is not fair for them to have to deal with.”

Since moving to the North Side in 2019 and commuting to work on the Southwest Side, Zanetti said the racial and socioeconomic disparities within the city are abundantly evident.

“It is very clear to me that City officials want to maintain this clear divide between the North and South Side neighborhoods, and the environmental racism that takes place in these communities is an unfortunate side effect of that injustice,” she said.

Mateo Curiel, a twelfth-grader at BOYCP stated his concern for their budding gardening club, and how the air quality would affect the plants’ ability to grow.

“Honestly, that’s really a shame because we’d like to have more opportunities for our students here. And so to hear that, it’s quite disheartening,” he said.

The disparity is apparent to BOYCP twelfth-grader Lorena Espinoza. “We live in a place where we’re surrounded by factories. Like you could walk North, East, West, South–you’re going to see a factory. And I feel like it definitely has to do with the fact that we don’t see any factories on the North Side. It’s more a general problem, and not just [of] Back of the Yards,” she said.

Guiffra believes students should not have to worry about their health. “Students should have a clean [learning] environment. It’s their education; it’s their future.”

On a small scale, installing air filters in classrooms has been shown to effect substantial improvements in student achievement, found assistant professor of economics at New York University Michael Gilraine. At the municipal level, Sambanis believes improved urban planning will ensure that schools are not placed between industrial zones with heavy traffic and equipment.

Furthermore, at the state level, there is a new bill (HB4093) that would invoke an “environmental impact review evaluating the direct, indirect, and cumulative environmental impacts to the environmental justice community that are associated with the proposed project.” This would entail a qualitative and quantitative assessment of emissions-related impacts to the area as well as an assessment of the health-based indicators for inhalation exposure.

Though these interventions will certainly alleviate the problem, it is imperative to ensure these issues are widely known in the first place.

A large part of Qazi-Lampert’s work focuses on making South and West Side residents aware of the environmental hazards that affect them. While some communities have the resources to be aware of what is happening in their environment, she said, there are others that just need more access to that information.

“A lot of folks may or may not be aware of what materials are put into the foundation of their schools and what the water quality [is like]. We tend to be very reactive when we see photos of dirty water or we see mold, like those are noticeable things. But it’s all about how do you make the invisible visible?” she said.

Furthering the discussion outside of school hours, Qazi-Lampert and the Climate Justice Committee are currently working with schools on the Southwest Side and beyond to win school renovations. Through speaking to teachers and initiating the Climate Justice Education Project, she and her team have been able to teach about eighty educators and community members on the concept of climate justice and climate awareness.

“Environmental justice is not just about the environment, it’s health justice, mental health justice, social justice, economic justice, and education justice,” she said. “And when we think about students and their learning environment, if their needs are not being met, then that learning experience is going to be quite challenging. So we want to make sure as a community that everyone creates an environment that’s safe. And our committee is doing the work to make sure this happens as soon as possible.”

Though the MCVD study can aid as a powerful decision support tool, it will be up to the public, community organizers, and politicians to change the policies surrounding Chicago’s greatest pollutants. According to Sambanis, this research will allow activists to initiate conversations in an intellectual way.

“Everyone cares about well-being, especially [that] of loved ones. And if we don’t do something or we don’t act, it’s only going to continue to get worse over time. It’s not fair, and it’s not right. No one deserves to be exposed,” he said.

Lily Levine grew up in Los Angeles and is a current student at the University of Chicago studying global studies and health and society. She last wrote about CPS layoffs.