A Small Space on the South Side

The space is in a city house building in Englewood,” said Cindy Eigler, co-executive director of the Chicago Torture Justice Center (CTJC). Right off of 63rd and Halsted, the entrance to CTJC is a little inconspicuous, but, since May 2017, CTJC has managed to create a home for survivors of police torture to meet and heal. “It’s accessible by train, it’s accessible by bus, it’s on the South Side. Those are all great things.”

When you enter CTJC, you are immediately greeted by decorations and photos created by the survivors themselves, and often survivors are working the front desk.

Moving further into the building, there are rooms for individual and group therapy, conference rooms, and a fully stocked kitchen. Eigler says the space doubles as a place for meetings and for community building. “We have a lot of people come and just sit with us or hang out with us and just do their own thing.”

But the center has its drawbacks. “[It’s] a small space, and it’s a mostly windowless space,” Eigler said. CTJC is in its last year of funding from the city, but Eigler said that with a promise from Mayor Lori Lightfoot to continue supporting the center, the chances of securing a better location are looking up.

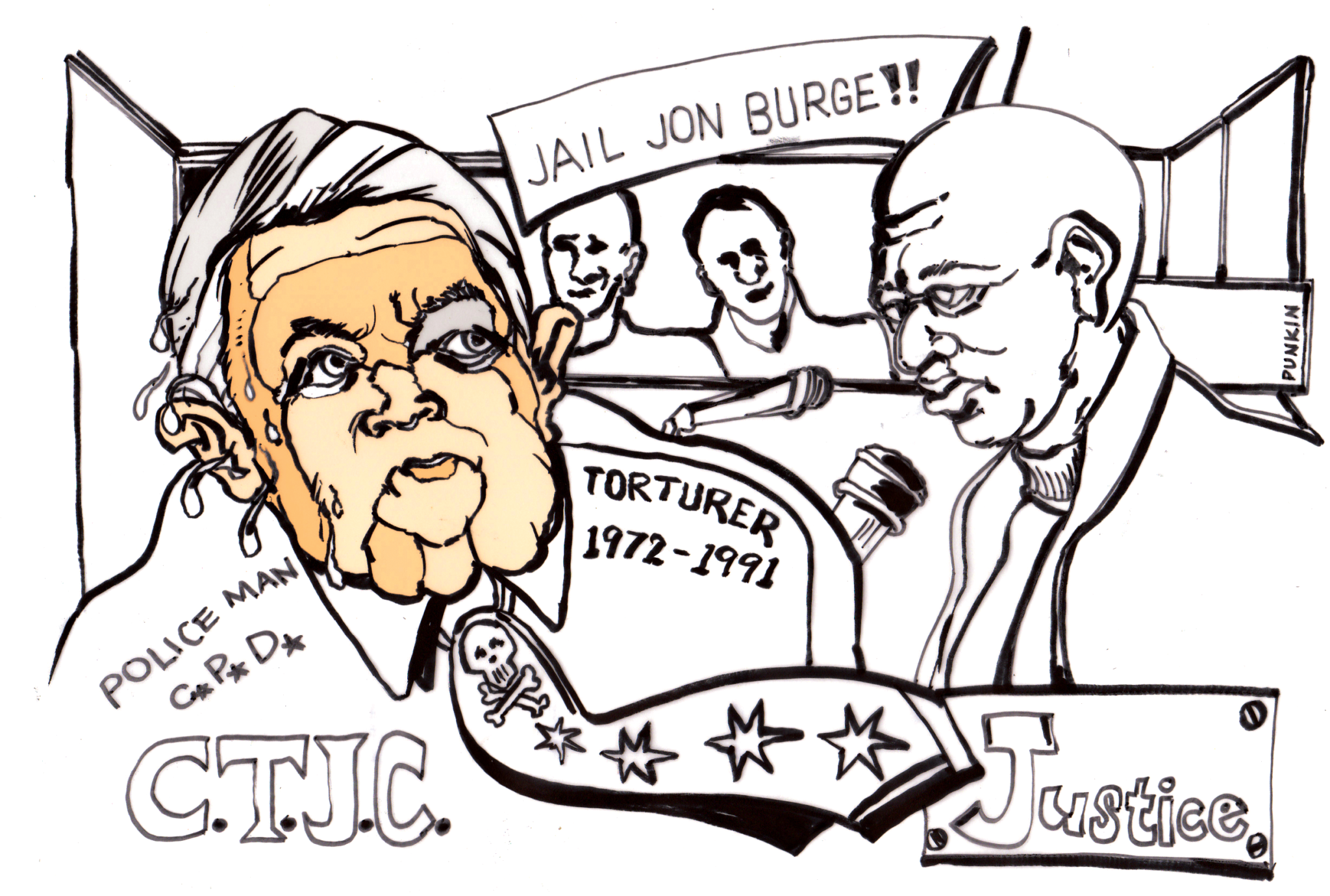

CTJC is a sister organization of the Chicago Torture Justice Memorial—both organizations are working to cement the memory of the Burge torture scandal, during which former Chicago Police Department detective and commander Jon Burge and his crew of officers and detectives tortured police suspects for nearly thirty years without any public or private repercussions, and, importantly, without any acknowledgement.

Around the center are portraits and photos created by torture survivors, along with captions on how they define resilience. One survivor wrote, “It is the ability to renew ourselves after something traumatic.”

Part of that renewal begins with remembrance. For decades, survivors of the Burge torture scandal tried to make their harm known, to no avail. Now, activist organizations in Chicago, families of torture survivors, and torture survivors themselves are working to enact truly meaningful reparations and to ensure that these stories are never forgotten.

The Long Road to Reparations

In 1975, Andrew Wilson and his brother Jackie Wilson were pulled over by Officers O’Brian and Fahey. Andrew shot and killed the two officers, and the brothers went into hiding for five days until Jon Burge, a Chicago Police Department detective and commander, and his “midnight crew” (the other detectives associated with him) found them.

The two were taken to CPD headquarters at 11th and State. There, Andrew Wilson was tortured for fifteen hours by as many as eleven officers until he confessed. The Wilson brothers were convicted of murder and Andrew was sentenced to death.

Andrew was the first survivor of Burge’s torture to come forward, filing a civil suit in 1983. Wilson testified six times under oath about what had happened to him (each time sobbing) and endured trial after trial for thirteen years while sitting in prison. He finally prevailed in 1996, when the Illinois Supreme Court judged, based on hospital documents, that the State had not demonstrated that Andrew’s confession was not coerced. Though he won his trial, Wilson received no money in damages and died in 2007 while serving a life sentence. Burge was fired from the police force in 1993, but the extent of the torture went largely unacknowledged in the decades afterward.

Wilson’s lawsuit was a crucial first step in bringing Burge’s crimes into the public consciousness. During a period officially recognized as extending from 1972 to 1991, but actually longer, Burge and his “midnight crew” tortured hundreds of men—mostly Black, but also Latinx—across the South and West Sides of Chicago. (The exact number is difficult to calculate—some survivors and relatives say it is around 500, while official counts usually place it at 120.)

Along with this work came Jon Burge’s indictment, largely a consequence of the testimony of survivors Melvin Jones and Anthony Holmes. A federal grand jury indicted Burge in October 2008 for lying about whether he tortured Black suspects. Ultimately, in late June 2010, Burge was convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice—not numerous counts of torture—and sentenced to four and a half years in 2011. He was released nearly a year short of that and died last year in Florida, a few miles from his retirement home in a suburb of Tampa.

Informed by all of this work, CJTM drafted the original Reparations Ordinance, intended to acknowledge the pain endured by survivors and go beyond the indictment of Burge. Activists intentionally identified what they sought as “reparations,” directly linking the racist brutality of Chicago police torture to the racist brutality of slavery. Once in negotiations with CJTM, City Council members dragged their feet for months. Finally, on May 6, 2015, then-1st Ward Alderman Proco Joe Moreno introduced a revised reparations package. After it passed through City Council, then-Mayor Emanuel took the stage and officially apologized on behalf of the city.

Holes in the Package

The reparations package was a way to hold politicians and the police accountable, and to finally offer meaningful redress to victims. It includes financial compensation, tuition-free access to City Colleges of Chicago, a public memorial to survivors, the establishment of the CTJC, and a curriculum implemented in CPS about the scandal and fight for reparations.

Alice Kim, one of the co-founders of CTJM and a leading advocate for the Reparations Ordinance, noted that the ordinance’s passage was a miracle in itself. “Given that for decades, it had been so difficult to obtain any form of justice, it felt in some ways like a pipe dream to actually achieve anything,” she said. The reparations package was the first of its kind: Chicago was the first city in the country to provide reparations to survivors of police torture.

Burge’s conviction also came as a surprise, but for activists and survivors the celebration couldn’t start there. “On the one hand, it was remarkable because no one had been convicted prior to Burge’s prosecution and conviction,” Kim said. “[But] even with Burge’s conviction, the survivors were still suffering from the trauma of police torture.”

Most notably, the package fails to provide reparations to all survivors of Burge’s torture, victims and relatives say.

One of the mothers, Bertha, noted that her son Nick Escamilla was not included in the package and received no reparations. “You first had to be a Burge victim…and it had to be from a certain year to a certain year, and a certain police station.” To receive reparations, victims had to have been tortured in Area 2 or Area 3, which together cover the South Side and downtown. “My son was in Area 1,” Bertha said.

While the package doesn’t fulfill all of survivors’ needs and doesn’t extend to all survivors of police torture, those who designed the package say that the Burge scandal was the best shot they had at meaningful reparations. “We picked the Burge torture cases because there has been so much work to document and unearth the evidence that there was this racist pattern of torture,” Joey Mogul, a partner at the People’s Law Office, the law firm that negotiated the reparations package, said.

“What we did was establish a precedent for giving reparations to people, and people should use our precedent and try to get reparations for others.”

While the package offers tuition-free access to city community colleges, it does not fund any other institution of higher education. Additionally, while the package requires that the city prioritize giving survivors and their families access to healthcare, it fails to cover expenses or ensure that survivors’ medical needs are accounted for. The vast majority of these shortcomings are due to a lack of funding, but some survivors criticize the design of the package for missing these key components.

Vincent Robinson, a torture survivor who now works as an artist, was frustrated by the lack of access to higher education beyond community college, and the failure to provide affordable housing and entry-level jobs for survivors. “The center is supposed to provide employment,” he said. “A lot of it is in stagnation, and the money that we had allotted for certain areas, I don’t see it being allocated. To me, I see it as a slap in the face to all of us.”

Mark Clements, another torture survivor, critiqued the city for not being open to a package that would truly acknowledge the value of the lives of the Black and brown people who lost so many years behind bars. “$100,000 to an individual who has served decades inside a prison is almost like a joke,” he said. “In reality, the problem is so big you need fifty centers to [solve] them.”

Clements also noted in particular the number of survivors that were left out of the package. Survivors of Burge’s torture regime that were tortured in the wrong location or the wrong year received no reparations.“And what about those guys that are still in prison?” Clements said.

CTJC is in its early years and has plenty of room—and plans—for growth. But it has encountered challenges in finding the funds to do so, since the city had originally only promised to fund the center for three years after the ordinance was passed. Eigler is hopeful, though: she said that in a meeting between then-candidate Lori Lightfoot and the Survivor Family Advisory Council, Lightfoot committed to continue supporting the center. Following her election, Lightfoot’s administration has said that they will welcome funding proposals, but Eigler says that they are still waiting to see if Lightfoot will follow through on that commitment.

Clements said that around one hundred potential torture victims are still incarcerated. Although activists in CTJC and CTJM are actively fighting for the release of these survivors, their reach can only extend so far with a small staff and limited funds. Still, Eigler said that they see this as a key component of reparations.

CTJC and CTJM, along with other partner organizations and nonprofits, are working hard to advocate for the importance of the package and elicit support from different sources, collaborating in their mission and their fundraising efforts to ensure that the movement is able to move forward.

“They Can Get It From the Horse’s Mouth”

It’s hard when somebody don’t believe you when you’re telling the truth,” said Anthony Holmes, whose early testimony played a large part in Burge’s conviction.

For survivors, one of the most important aspects of reparations is ensuring a public memory and receiving acknowledgement of the torture that they suffered, as well as the torture that all victims of police violence and their families have been put through. There was no public acknowledgement of Burge’s torture for more than thirty years. When survivors and their families tried to speak out, the vast majority did not believe them.

Mary L. Johnson, one of the first mothers of a torture survivor to come forward with a complaint against Burge in the 1970s (her son, Michael Johnson, is still incarcerated), also faced significant backlash, and she said that all of the other victims’ family members who filed complaints with her—forty-six in all—dropped theirs due to threats from Burge and his crew. “I’ve been out here a long time,” she said. “And I don’t want this to die down.”

The “Reparations Won” curriculum was established by the ordinance and requires all Chicago Public Schools to educate students about the Burge torture scandal and the path to reparations. The curriculum has been established successfully in majority Black and Latinx communities but largely delayed in majority white communities where parents are extremely resistant.

At Wildwood Elementary on the Far Northwest Side, which is sixty-two percent white, parents were especially upset. Parents called the curriculum “insane” and complained that it was not telling the whole truth. “And then all the mugs that supposedly were ‘victims,’ are they gonna have their rap sheets, which are probably longer than this table? Are they gonna show these kids that? That’s what I wanna know,” said one parent.

The principal and other staff members tried hard to educate parents about the importance of the curriculum, but with little success. Principal Mary Beth Cunat faced outrage from parents at the school due to the curriculum, in addition to an instance where she invited police abolitionist Ethan “Ethos” Viets-VanLear of We Charge Genocide to speak at the school. She eventually received personal threats from parents.

On June 6, 2018, two weeks before the end of class, Cunat resigned.

“The good thing about it is, we’re not dead,” Holmes said. “They can get it from the horse’s mouth.” Holmes is a member of the CTJM advisory board and actively advocates for a public memorial as well as for more funding to be given to CTJC, so that services can be provided to survivors that acknowledge the widespread effects of police violence on entire communities.

CTJC and CTJM have recently begun a committee that they call the Spokes Council to more specifically address different aspects of reparations, and they have partnered with the Chicago Teachers Union, CPS, and the Invisible Institute (an editorial partner of the Weekly). CTJM also released a Report Card on Reparations in the primary stages of the mayoral election to evaluate different candidates on their dedication to honoring the reparations package and to acknowledging Chicago’s history, and the present effects, of police torture.

Holmes and other survivors hope that with the memorial and the CPS curriculum, it will become more difficult for further erasure of police violence to occur. “We’re here. And therefore we speak what we feel and what happened to us. It wasn’t just Burge, it was the whole crew, they were going on a city rampage and torturing people and getting away with it. That’s pure history, you can’t deny that, it’s going to always be there, and we’re trying to get something to go along with that.”

Building A Public Memorial

One of the biggest undertakings of the reparations package has been the creation of a public memorial. In May, a design—created by Patricia Nguyen and John Lee—was finally picked for the memorial after a month-long exhibit at the Arts Incubator that showcased different ideas.

A self-contained, spiraling grey building, Nguyen and Lee’s memorial bears the name of everyone who has been tortured, and contains a space for visitors to leave written reflections. In a statement, the artists said, “We envisioned a monumental anti-monument, where time does not stand still within the memorial to commemorate a history as past, but a past that is still present.”

Ultimately, however, Eigler said that even the building of the memorial won’t close the book on the fight for reparations. “I think the message that we’ve gotten is that the memorial won’t ever end up being just one thing,” she said, mentioning ideas for having archives at CTJC and further exhibits.

There isn’t currently a designated site for the memorial, and CTJM is still in the process of negotiating with Mayor Lightfoot’s administration regarding funding. But survivors and activists have said, again and again, that this is just the beginning of their work. Robinson made it clear that the sacrifice of survivors’ lives that had been made could never be fully repaid: “Us, as survivors, we refuse to just let it go away. Because never can you compensate nobody for their life or their time that you’ve taken away. No monetary amount can be given to compensate.”

Ashvini Kartik-Narayan is an education editor at the Weekly and a student at the University of Chicago majoring in public policy. She last wrote for the Weekly about spoken word poetry’s roots in Chicago.

Maddie Anderson is a contributor to the Weekly. She recently graduated from the University of Chicago where she wrote her thesis entitled “What Makes An Ideal Reparations Package?: A Typological Examination of Reparations for Jon Burge Torture Survivors,” forthcoming in the Chicago Studies Annual Journal, which parts of this article are based on. She is now a teacher at Mt. Pleasant High School in San José, California, and pursuing her masters in education.

This story was so touching.

We will have our day in court we ain’t going away