The Renaissance Society has been breaking boundaries since it opened in 1915. In keeping with this tradition, artist Mathias Poledna is helping the gallery celebrate its centennial by literally dismantling its structure, making room for the next century of transgression and innovation.

He has removed the gallery’s steel truss-grid ceiling, an emblem (and tool) of the space since 1967. Removing the low ceiling dramatically changes the atmosphere in the Renaissance Society. Now only glimpses of light from the installation, and back offices, illuminate the arching walls and vaulted, white ceilings. Poledna is the first artist to physically alter the gallery so dramatically, an act that asks viewers to consider both iconoclasm and the nature of material property.

A 35mm film installation will accompany the altered gallery space, creating a dialogue between the historical legacy of the Renaissance Society and the avant-garde artworks within it.

“I’ve been following Mathias Poledna’s practice for a number of years,” says curator Solveig Øvstebø. “It was interesting to work with Mathias here because I knew he would ‘attack’ the institution—go deep into the institutional memory, history, structures—and I was curious about what he would draw out in the new work.”

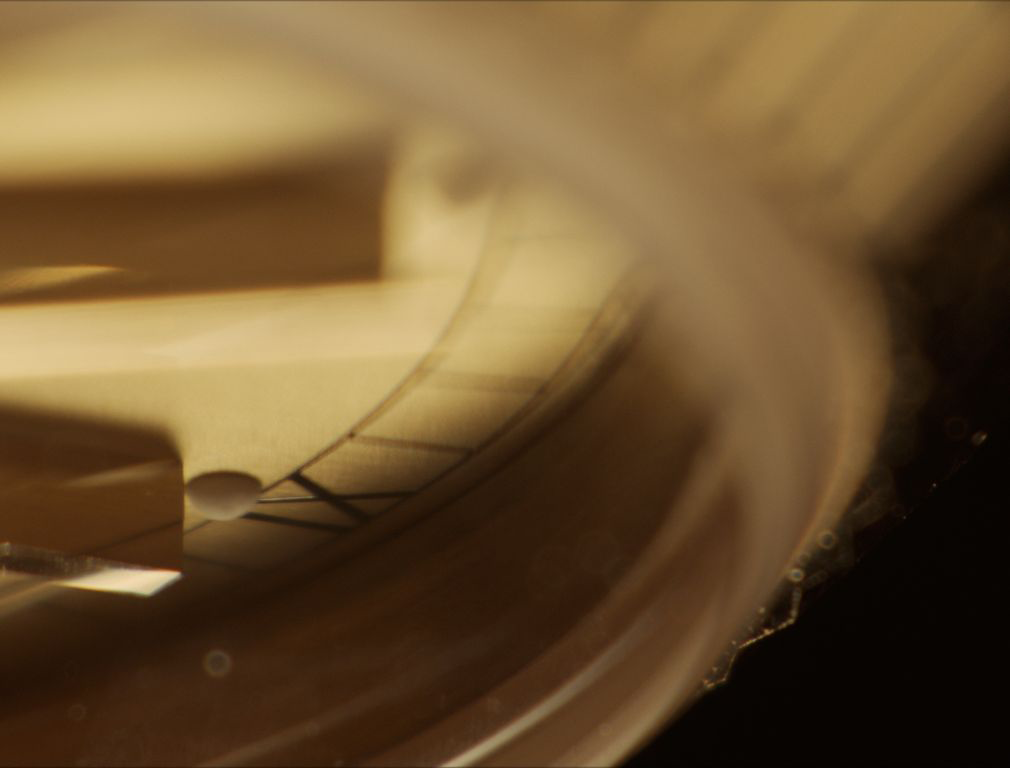

The grainy 35mm film focuses on the inner mechanisms of a Rolex watch, the analog film mirroring the analog workings of the watch. Without context, the video may feel a little like a Rolex commercial featuring artful shots of the watch’s face and a catchy instrumental soundtrack. However, the film is not all glamor shots. It zooms in on the miniscule cracks and dust on the watch’s face.

“Look at the dust on it, even though it’s this expensive piece of real estate on your body,” a visitor says to his friend. They are both students of photography at schools downtown. “I know, look at how much more complex it is as the video goes on, even the soundtrack builds up.” And it does. As more of the face of the watch was shown, I found myself leaning forward in interest, reeled in by the instrumental rhythms. Something about the score is reminiscent of ticking, building in volume and rhythmic depth as the intricacies of this luxury item are showcased.

The Renaissance Society sees Poledna’s dismantled overhanging grates and his film as a way to usher the space into its second century as a leading modern art gallery. Installed in the 1960s for student exhibitions, the grid has remained a feature that all artists must face—either by engaging or ignoring its imminent presence above their heads. Director of Communications Anna Searle Jones describes its removal as a “positive disruption,” as it frees up space, and allows for artists to engage with the Renaissance Society’s environment in new ways.

Jones discussed with me the Society’s ongoing mission to build an identity independent of the University while acknowledging the aims and accomplishments of their founding faculty. These founders secured big name shows like Picasso, Braque, and Miro back in the day, and Smithson, Gonzalez-Torres, and Kiefer in the latter half of the past century.

“We have a really free space,” Jones tells me. “We value our independence because we are one of few non-collecting museums in the country that allow artists to take large risks, and we’ll support their work. They know to come to [The Renaissance Society] with their uncertain ideas, and new questions to discover.”

The restructuring of the Renaissance Society is a timely transformation. With a new website going up, and a full program ready to fill the first quarter of their second century, the Renaissance Society is just as relevant as ever.