Another spring day begins at Bronzeville’s Mollison Elementary School. Two blocks away, a seventh grader yanks at the arm of his little sister. She’s insisting on picking a palmful of yellow flowers for a friend’s birthday, but her brother knows the consequences for arriving after nine o’clock. They scurry in, just in time.

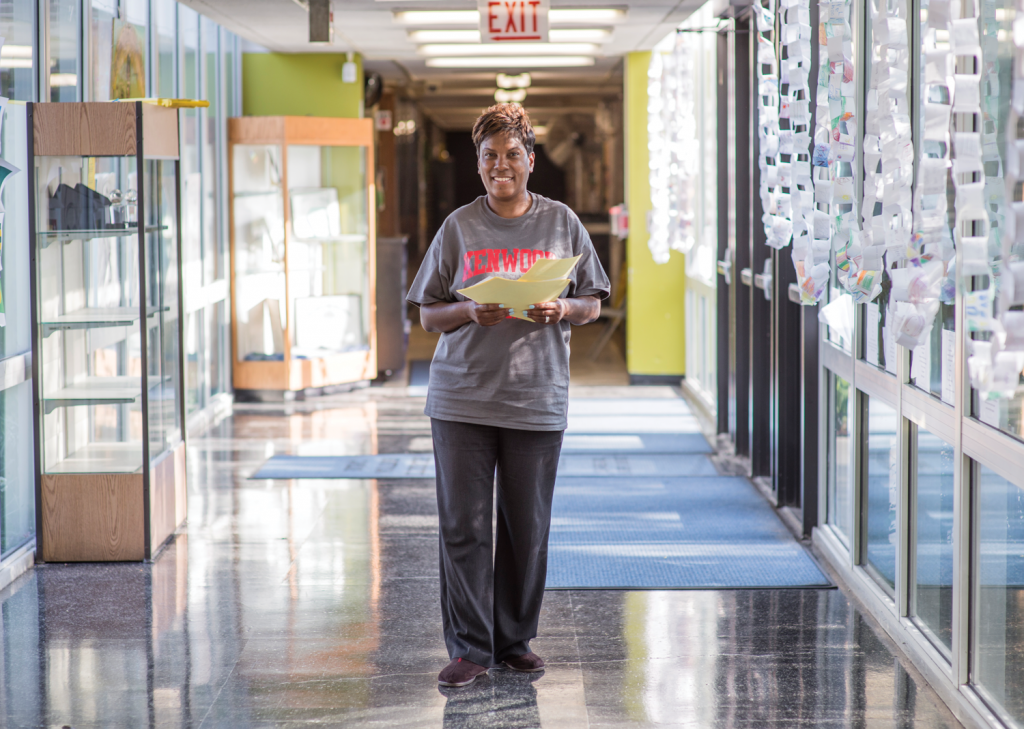

Inside, they’re greeted by Principal Kimberly Henderson, dressed down in a grey Mollison P.E. t-shirt. Squatting on her haunches for the kindergartners, she greets each of the children who passes through, then heads into her office to start the school day. As her cheery “Good morning, Team Mollison” over the P.A. system transitions into a drone of announcements about impending tests and visiting book fairs, Ms. Takyra Flowers instructs her eighth grade reading class to continue with their semester-long research projects, preparing them for the work they will see next year in high school. The girls scramble up from their seats, chattering as they make for the district-provided gray iPads by the side of the classroom.

In the arterial hallway that runs through the front of the school, Ms. Linda Thomas, one of two first grade teachers, gathers her charges. On this particular Friday, the first and second graders are going on a field trip to the Brookfield Zoo, located fifteen miles west of the city. The cul-de-sacs, wooden forests of Brookfield are a change of pace for these roughly 100 kids, most of whom will have spent their entire lives in the blocks immediately surrounding Mollison, a dense center of activity on what is otherwise a quiet stretch of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

But these kids are all seven or eight years old, and there are more immediate treats in store today. After all, there are monkeys at the zoo. “There are monkeys! I’m going to see monkeys! I LOVE monkeys!” one boy exclaims to a friend, now just as excited. “I love monkeys too!”

I’ve spent three months at Mollison Elementary, speaking to school leadership, teachers, and parents, and I have seen the Mollison community work tirelessly to maintain a sense of normality in the midst of a year of upheaval. Academic success, student safety, and cooperation between the principal and parents remain sacrosanct goals, even if the challenges of the past year have presented themselves on a scale Mollison has never seen before. On the first anniversary of the school closures, it’s time to ask: how exactly was an otherwise unremarkable school like Mollison impacted by this huge change?

In the past twelve months, Chicago has closed fifty elementary schools that it deemed “underutilized” and a drain on district finances. The closings have had a disproportionate impact on the city’s South and West Sides, which has led to accusations that Mayor Rahm Emanuel and his appointed school board have failed to adequately care for the plight of Chicago’s African-American population.

Overton Elementary, long a mainstay of the Oakland neighborhood and a ten-minute walk from Mollison, was one of those closed schools. Its 431 students were left to find alternative educational accommodation for the next school year. The vast majority of them made their way to Mollison, their designated welcoming school, whose population grew from 237 to 510.

The new and unpredictable challenges associated with the drastic increase in population are compounded by a litany of familiar worries. Money remains tight, given the district’s high-profile budget deficits, with the extra funds designated to ease the process of school consolidation due to expire after just one year. There’s also never enough space. One of the school’s proudest after-school programs is its association with the Joffrey Ballet Company. The room they had dedicated just for dance last year was turned into a classroom, so eighth graders must push the library tables to the side twice a week to make room for their dance lessons.

On the second floor of the school, thirty boys in the sixth grade have their heads bent in clusters of tables, working together on a word search centered on the themes and characters present in Brown vs. Board of Education. It’s not all quiet, and there’s a tension in the air. The two fastest groups of five are promised chocolate at the end, a prize tantalizing enough to focus most of these active twelve-year-olds. But some within the classroom still have bigger problems with group work, and need reprimanding or closer supervision from Ms. Amanda Hurst, a fresh college graduate in her first year in Mollison.

Each Wednesday morning, instructors from the citywide Umoja Student Development Corporation come to this sixth grade class to lead rigorous courses designed specifically to prepare these students for college. For most of the spring, the curriculum has been dominated by seminal events in black history. This week’s focus on educational equality and progress is timed especially well, coming just two weeks before the nation marks the sixtieth anniversary of the Supreme Court decision to outlaw segregation in the nation’s public schools.

“Did you find Earl Warren?” One boy’s voice rings through the chatter, reaching a crescendo as the groups inch closer to the end. The reply soon comes. “No, but this is the 14th Amendment right here in the corner!” The five closest to the door leap up in triumph, and those who missed the remaining clues (Topeka; equality) explode in minor recriminations.

The conversation meanders toward a lengthy discussion on the adverse psychological effects associated with school segregation. One shy boy hesitatingly reads aloud from a PBS overview of the landmark decision that struck down legalized segregation in the nation’s public schools, urged on by his teachers when he stumbles over the word “unconstitutional.” A classmate speaks glowingly of the progress made in this bygone era: “There were black schools and white schools, and then they stopped being unequal!”

Today, Mollison is ninety-nine percent black, and more than four-fifths of its students qualify for reduced price lunches. Most of Mollison’s sixth graders will go on to the nearby Wendell Phillips Academy High School. In 2013, about thirty-nine percent of Phillips’s students graduated from high school in four years, compared to a statewide rate of eighty-three percent. Of that pool of graduates from Phillips, just slightly over half will make it into college at all, and another half of those will graduate with a diploma. If those trends hold, only three of these boisterous boys are likely to make it into the working world armed with a college degree.

Principal Henderson has been at the school for two years, and she is acutely aware of the odds that her charges face. For one, the students she receives differ greatly in their individual aptitudes, and making sure that an education at Mollison works for each student is particularly difficult. Work that is designed to prepare a student for the rigors of college is unlikely to be well-received by students who struggle with the basics.

“My higher-performing students have not shown the growth we wanted them to show this year. What that says to me and my staff is that we have to differentiate our instruction, to challenge them,” Henderson says.

However, that desire to push students to a higher level is stymied by an acute lack of resources. There’s a hint of exasperation in her voice as she rattles off a series of hypotheticals: “Do I have the staff to challenge them? Do we have the resources to do that? Where do you get more challenging, more advanced work from?”

She insists that these are not problems unique to Mollison. Principals in cash-strapped schools around the city are also similarly bound by the opposing demands of providing advanced work and remediation within the same classroom.

But Principal Henderson is unfailingly optimistic. She smiles when she recounts the deep hope she holds in her sixth grade classes. The sixty-one boys and girls constitute what is currently the highest performing grade level in her school in both reading and math, as measured by the mid-year Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) assessments mandated by the state of Illinois’ move to a Common Core curriculum in 2010.

Thirty seventh and eighth graders participate in Spark Chicago, a national program that provides apprenticeships throughout the city. Principal Henderson explains that this early exposure to the workforce has untold benefits for her “sparklers,” both academically and socially.

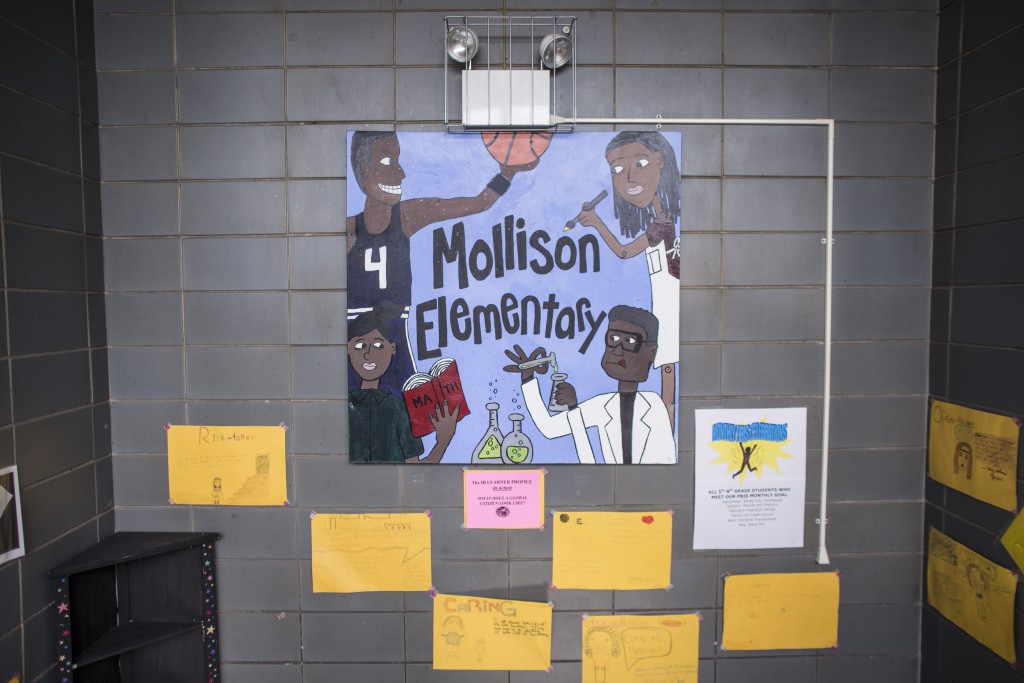

Despite the school’s strapped budget, Principal Henderson has tried to create a college-going culture in the school. It’s impossible to go two steps in Mollison’s hallways without seeing yet another university pennant, and there are college weeks, where teachers sign up to explain the benefits and attractions of going to their own alma maters.

The recent transformation of the school’s academic culture has had noticeable results. At the end of the 2012-2013 school year, one year into Principal Henderson’s tenure, Mollison gained a much-coveted Level 2 designation from CPS, an improvement from its long-held status as a Level 3 probationary school. Moving away from the lowest possible rating has provided a shot in the arm for the school, and both the principal and staff are fiercely determined to hold onto those signs of progress.

It’s March, just two weeks before spring break, and there are three inches of snow on the ground. Twenty parents and teachers pack into the school library for the monthly Local School Council (LSC) meeting. They unpack Subway sandwiches for an early dinner.

To some particularly vocal parents within the LSC, the influx of Overton students has been handled shamefully by those in power. They believe that the neglect of Mollison after the closing decision is part of the school board’s racist agenda against black families like theirs.

Irene Robinson, long a mother and now a grandmother of Mollison students, is especially piqued. Today, conflict erupts over the proposed summer addition of several mobile units to provide extra rooms for classes and extra-curricular activities in a school where space is now at a premium.

Raising her voice, Robinson situates the school’s current plight in the context of CPS failure. “The board does not care about our children. If they did, they wouldn’t have closed our schools!”

Jeanette Taylor-Smith, president of the LSC and the mother of two Mollison students, ups the ante further. She compares the proposed solution to Mollison’s lack of space to Chicago’s infamous Willis Wagons, referring to the 1961 decision to add portable classrooms to overcrowded black public schools instead of more systematically desegregating the wider public school system.

“This bullshit would not happen up north! I’m tired of being the only voice of reason that says our black kids deserve better.”

To parents like Taylor-Smith, the addition of Overton students to the settled and steadily improving Mollison Elementary has been a disaster. These changes have taken a physical toll on her.

“This year’s been chaotic. Hectic. Overwhelming. It’s ten times worse than I thought it was going to be.” Trembling and tired from the stresses of the year, Taylor-Smith explains why she continues to feel so strongly about a political fact that she realizes is unlikely to be reversed.

“There’s no connection between 125 S. Clark [CPS headquarters] and 4415 S. King Drive [Mollison’s address]. They don’t have a clue. They’re too busy looking at us on a spreadsheet.” She went even further than fingering bureaucratic neglect as the cause of what she sees as Mollison’s difficult year. To her, CPS under the leadership of CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett is actively undermining the efforts of parents like her in schools like Mollison.

“It’s sabotage. It’s like you’re throwing a grenade in the school, and the LSC are the people who are targeted and made to fix it.”

Taylor-Smith reserves her strongest emotions for the sense of cultural loss that has come with the closures. She was a Mollison student herself, and the closures meant the erosion of many things she held dear.

“The district isn’t taking into consideration that this is the only neighborhood school within a long range that people are bringing their kids to because of that reputation for being a family.” Her voice cracks, and she takes a deep breath. “But that reputation is ruined. It’s totally ruined. It is so ruined.”

Principal Henderson is sympathetic to the parents’ impression that this year has been a drastic departure from the way Mollison was run in the past. She lets on that this has not been an easy transition for her either.

“It really feels like I’m in my first year at this school again, because the two years have been so drastically different from each other,” she says. “As far as setting expectations, creating the learning environment that we want to have in our school, we had to really start almost all over again.”

But Henderson rejects the sense of doom prevalent in the LSC, and she explains that it is all too easy to exaggerate the scale of the challenges associated with combining the two schools.

“We’re not integrating earthlings and aliens. It wasn’t that severe. Their cultures were not very different from one another.”

Instead, in a peppy flourish, she focuses on the benefits of having more students attending the school. “We have kids now. We’re a vibrant school! We have to turn people away. I would much rather be in that position.”

First grade teacher Ms. Thomas is one of three teaching staff who came over from Overton and stayed the entire year. Having worked in both places affords her a perspective not available to many parents. To her, their criticisms are founded only on an incomplete picture of Mollison.

“The members of the LSC are here, but they’re not actually here every day. They understand just bits and pieces, parts of the puzzle. I know it’s hard. It was always going to be hard during the first year.”

Instead, she offers up unvarnished happiness at the way the school managed to include her within the larger Mollison family. “Overton was my home for twenty-one years. It was going to be hard for me,” she says. “At first, I felt like I was going to be the stepchild, like Cinderella. But when I came, everybody was welcoming, everybody just opened their arms.”

She credits the ease of that integration to Principal Henderson. Thomas refuses to accept the LSC’s vocal criticism of the way in which the school closures were handled. “As a teacher, I know what Mrs. Henderson does. She’s doing a fantastic job. She’s with us, she’s in the trenches with us. I don’t understand the LSC’s perspective of what’s going on in this school.”

Principal Henderson hopes that the day will soon arrive when everyone associated with Mollison stops thinking of it in relation to the school closures, a day when she can just focus on finding common ground with parents in pursuit of their shared goal of ensuring that their kids get the best education possible.

“I just want us to move away from the political argument, from whether we agree or disagree. It is done, and I’m here to do the best I can in my situation. These disagreements take up too much of our time and energy,” she says.

She ends her defense of the past year with an impassioned plea for cooperation in the future. “We all want to be focused on what we can do best for these kids. We’re just Mollison now, and these are all my babies too.”

In the past year, the biggest upset at Mollison did not come from any long-standing political disagreement.

On March 31, the school gained citywide attention after an eighth grader, Leon Bell, was arrested after he brought a loaded gun to school and sent pictures of himself with it to two friends. Charged as an adult because he had a previous record, Bell currently faces one count of unauthorized use of a weapon on school grounds.

Principal Henderson was the one who discovered the pictures, almost by accident, when she was checking another student’s cellphone for pictures for something else. Nearly a month later, she still found the unwanted publicity difficult to deal with. “It was devastating to me. It was a traumatic experience for me as a principal.”

Intent on making sure that her students understood the implication of Bell’s decision, Principal Henderson reached out to the Chicago Police Department to bring its Gang Resistance Education and Training (GREAT) program to Mollison.

At the end of April, a class of eighth grade girls lobbed question after question at Officer Beamon, a police officer in a baby blue uniform with tightly cropped hair, representing the GREAT program at Mollison for the first time. Beamon had never interacted with this class of twenty-eight girls before, but she quickly established a rapport with a group that was intimately familiar with the specter of violence in their communities.

Slowly searching through the recesses of her memory, a student told the class about a murder she had seen in Bronzeville in the recent past. “This girl, she was in the neighborhood,” she began. “She was up by the front door, she was smoking a cigarette. Some people just came up and started shooting at the house, and she got shot in the back. She died.”

The sympathy was unmistakable in Officer Beamon’s voice. “God bless her soul. That’s horrible.”

“You know what? I work with a lot of kids,” she said to the group. “I know y’all go through stuff that kids elsewhere don’t go through, that adults in their sixties and seventies never experience.”

She also took the opportunity to rail against the idiocy of bringing signs of violence into the school, gently informing a girl who thought of Leon as a friend that what he did was simply stupid.

“On bringing guns to school, I have a complete zero tolerance, because things could have gotten real bad, real fast with that one. Whatever is going on in his mind where he thought it was okay to bring a gun to school, he needs to be evaluated.”

Principal Henderson tries to paint this an isolated incident, not in keeping with the culture she has tried to build within the walls of her school. “It’s one child who made a mistake. It’s not indicative of our school. I shudder to think that a child in my building feels it necessary to have a gun, but no one was hurt.”

After all, a school can only do so much to tamp down the violence present in the wider communities of which it is a part. When Bell slipped a gun into his backpack that Mondaymorning, Taylor-Smith suspects it was likely in response to the gang territory he had to pass through to get to school rather than any threat he was going to face once within Mollison’s walls.

Principal Henderson beseechingly underlines the difference between the street and the school. “Our neighborhoods and the violence that happens is not about CPS, and people need to separate the two. People need to recognize that, instead of blaming everything on the school system, because that’s not fair.”

On this, Taylor-Smith finally concurs. “He’s just a kid. He made a mistake. His mother is scared. They’re just trying to make an example out of a kid, and they shouldn’t.” She sighs, and tells me that she and the members of the LSC will be there during his day in court to support his mother.

That spring Friday morning, Principal Henderson’s rundown of the day’s announcements goes on. It goes on above a tinny Solange song from the gymnasium, where the eighth grade girls have congregated in groups of three or four, twisting, dancing, smiling, and waiting for P.E. class to start.

It goes on above the quiet swish of a janitor’s mop, signaling the end of breakfast—egg and turkey sausage, stuffed into a breakfast burrito—for those who qualify and who arrive before nine.

“Attendance has been great this week. Ninety-seven percent of you came to school on Thursday. I am peacock proud!” Principal Henderson continues, over a girl’s grumbling at being caught with a too-short skirt. “Do you really need to call my grandmother?”

Three minutes pass. The first and second graders have stepped out in single file and loaded themselves onto three bright yellow school buses. Teachers have shepherded latecomers into classes, and now there is nothing but belated quiet in Mollison, nothing to disturb Principal Henderson as she speaks.

“There was a thunderstorm earlier, and I hope you all got into school safely.” It’s the end of the school’s spirit week, five days dedicated to celebrating their collective pride in Mollison Elementary. “But as we all know, after the rain comes the rainbow.”

I was a student at Mollison in the ’70’s. It was a very good school then also, we had that family feeling about the school, also. I think it’s not the school but the community that has changed. It would have been unheard of for a child to come to school with a gun in those days. The students are afraid to walk in certain areas, and maybe Leon felt he had no choice but to carry that gun. I loved Mollison and my friends, and I hope that things get better for the staff and students.