If you lived in Pilsen in 2005 and wanted to get to the Loop, you might have walked to the 18th Street station and waited. And waited. And waited.

At the time, 18th Street was part of the Blue Line’s Cermak branch. Similarly to how the current-day Green Line splits at the Garfield Boulevard station, Blue Line trains coming into the city from O’Hare would turn west from downtown, and then hit a fork at Racine. Half would continue on in the median of the Eisenhower Expressway towards Forest Park, and half would turn south onto the elevated tracks towards 54th/Cermak.

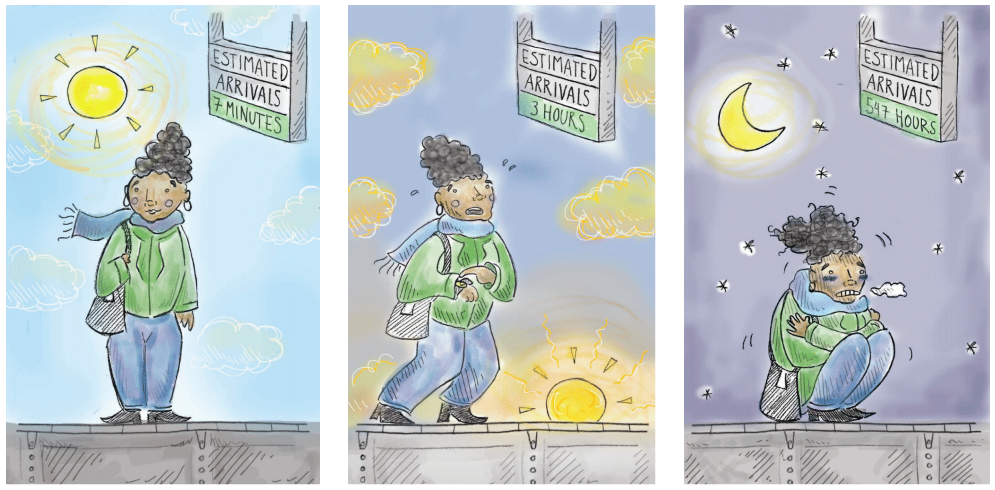

That meant that on each of the West Side branches, there were only half as many trains as on the O’Hare branch on the Northwest Side. And that meant waiting. A Blue Line commuter in Wicker Park in 2005 could expect a train to come every seven or eight minutes at rush hour. But in Pilsen or Little Village or Lawndale, schedules called for trains every twelve to fifteen minutes. And at less busy times—evenings or weekends—they might have been as much as twenty minutes apart.

In 2006, the CTA created the Pink Line from the Cermak branch, which allowed frequencies to increase dramatically. Today, rush hour trains are scheduled at 18th Street about as often as they came to Wicker Park in 2005. Unsurprisingly, riders have responded: while the eleven stations that made up the Cermak branch saw about 3.2 million people enter their turnstiles in 2005, that number was up to 5.2 million by 2016.

But on today’s South Side, the branching problem that used to haunt the West Side still exists. Heading South from Garfield Boulevard, the Green Line splits into two spurs that head east and west along 63rd Street. And that means residents of Woodlawn and Englewood are still playing a waiting game.

While headways (the time between trains) at rush hour are eight minutes on the Pink Line and as low as two minutes on the busy Red Line, passengers at the King Drive, Cottage Grove, Halsted, and Ashland Green Line stations must budget as much as fifteen minutes of waiting on their platform. And outside of rush hour, headways stretch up to twenty minutes.

As a consequence, all four stations on the Green Line branches have very low ridership—even though the neighborhoods around both branches have population densities at or above the citywide average, are close to major anchor institutions (the University of Chicago and Kennedy-King College), and offer transfers to some of the city’s most-used bus lines. Cottage Grove and Ashland/63rd, each at around 1,200 boardings a day, see fewer passengers than every other terminal in the system except for distant, suburban Linden on the Purple Line. Halsted and King Drive, for their part, rank 144th and 145th for ridership—out of the L’s 146 stations.

Nationally, transportation experts tend to agree that somewhere between twelve and fifteen minutes, a transit service ceases to be “show-up-and-go,” and forces riders to time the beginning of their trip according to a schedule. But many CTA riders—particularly on the South Side—use a bus to get to the train, meaning that they can’t plan for a short wait when they transfer.

The waits add substantial time to what is otherwise a quick trip. Once a train leaves the Ashland/63rd station in West Englewood, it takes barely half an hour to reach the Loop, creating an important link between a neighborhood that has suffered years of disinvestment and North America’s second-largest job center. But the long waits for a train mean that riders need to budget as much as fifty minutes, not thirty, to actually make the journey—turning a reasonable commute in a big city into much more of an ordeal.

The problem is so bad that it is sometimes faster for a person going downtown from the Ashland/63rd station to take the bus four miles north and transfer to the Orange Line than to wait for the next Green Line train.

In many ways, too, the wait time is worse than more frequent, but slower, trains: studies show that riders strongly prefer an extra minute of travel to an extra minute of waiting for a train or bus to show up. That preference is likely to be even stronger in Chicago, with above-ground stations open to often unpleasant weather.

This year, the City of Chicago has announced two major overhauls of two South Side Green Line stations: Garfield, the last stop before the tracks split; and Cottage Grove, the terminal of the Woodlawn branch. The renovations and reconstruction at the Garfield stop alone will cost $50 million. At the same time, a social media campaign has emerged aimed at restoring the last mile of the Woodlawn branch, which ran from Cottage Grove to Stony Island and was torn down as part of a complete overhaul of the Green Line in the mid-1990s. That extension would bring it within a block of the proposed Obama Presidential Center, a major activity and job center.

But without addressing the waiting problem, these projects miss an opportunity to address the biggest impediment to high-quality service on the Green Line’s 63rd Street branches—and will likely fail to attract significant new ridership.

So what can be done?

Since each branch has only two stations, it doesn’t make sense to create a whole new service, the way the CTA transformed the Cermak branch into the Pink Line. But the CTA could create a sort of shuttle service that would have a similar effect.

Here’s how it would work: Instead of switching off between the Englewood and Woodlawn branches, all regular Green Line trains would just use one branch, going either from the Loop to Woodlawn or from the Loop to Englewood. That would bring headways on that branch up to normal levels for the rest of the line—seven or eight minutes at rush hour, and ten minutes most of the rest of the day.

Meanwhile, the other branch would get a “shuttle” train that ran between the terminal and Garfield, where passengers could transfer to the regular Green Line. With identical headways on both branches, the shuttle could be timed to arrive at Garfield to allow transfers with minimal delay, and then head back to its southern terminal.

One impediment to this sort of service is that it may be difficult for the shuttle to turn around at Garfield without interfering with regular Green Line trains. But with the planned redesign of the Garfield station, officials could chose to solve this problem by rearranging the tracks to make such turnarounds possible.

Whether the city implements a shuttle service or some other arrangement, until they do so, the city is squandering a valuable resource in those four South Side Green Line stations by running infrequent service to them—and residents of Englewood, West Englewood, and Woodlawn, as well as neighborhoods with bus service that connect to those stations, are missing out on what could be first-class transit access to downtown and the rest of the city.

Daniel Kay Hertz writes about Chicago and urban policy. In addition to South Side Weekly, he has been published at the Chicago Reader, Chicago Magazine, The Atlantic and the Washington Post. He currently works for the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, though all the opinions in this piece are his alone.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Like a Skokie Swift but for Woodlawn/Engelwood! I like it.

Wasn’t the conversion of the green line’s Normal Park branch into a shuttle service part of the reason for its decline and eventual abandonment?

Restoring the 58th Street Station for the shuttle transfer would be easier. there are already trackswitches there, it is an island platform, and immediately adjacent the turnoff to Ashland. I strongly support restoration of the Jackson Park Branch to Stony Island, including intermodal transfer facilities to the MED. The long term plans ought to include extending the Ashland Branch to Midway making the airport far more accessible from the South Side both for travelers and ground services staff.

In the mean time, CTA could halve the headways on the Green Line south by through routing the Pink Line increasing service without adding Loop throughput.

If Red Line trains are running so frequently on the north side, couldn’t a few of them, rather than continuing to 95th/Dan Ryan, go to one of the 63rd Street terminals instead?