Organizers from Chicago and around the country gathered at the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) Center Friday through Sunday, November 22–24, for a conference to re-found a historic civil rights group known as the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR), with the aim of forging links between grassroots movements for racial justice and police accountability nationwide.

The conference began with a rally that filled the union hall, featuring speakers from the city and across the country, including academic and activist Angela Davis.The following days were devoted to workshops that sought to build connections between local and national movements through topics like building community control of the police and fighting local law enforcement’s collaborations with federal authorities.

Chicago is no stranger to community organizing around these issues. The National Alliance’s Chicago chapter participated enthusiastically in grassroots campaigns around police violence and accountability. It led a citywide push for a Civilian Police Accountability Council (CPAC) and pursued reparations for the hundreds of mostly Black Chicagoans who were tortured and unjustly imprisoned by the Chicago Police Department, particularly under the infamous Commander Jon Burge.

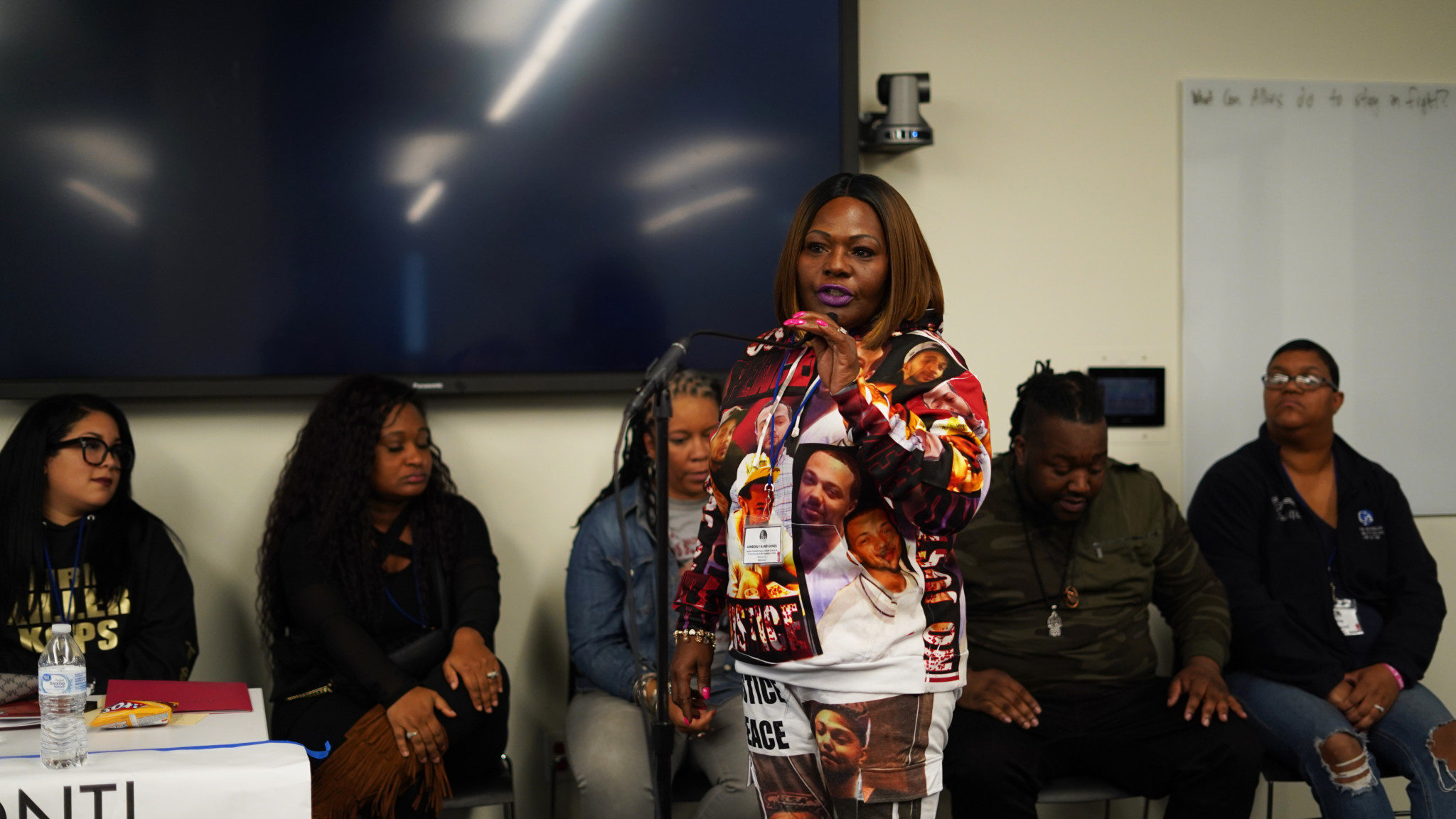

One such survivor is Gerald Reed. At the conference’s opening night rally, his mother, Armanda Shackelford, spoke about the Chicago Alliance’s role in his defense. Despite having his conviction overturned a year ago, Reed remains imprisoned as hearings for his release continue, and his physical well-being declines. He’s been imprisoned now for almost 30 years.

“They’re fighting every day to free my son. But it’s not just Gerald Reed, because Gerald is not in there by himself,” Shackelford said. “When my son was arrested in 1990, if we had CPAC, he would not be in jail. But it happened and it still happens.”

Grassroots efforts to hold the city accountable for police torture resulted in Burge’s conviction on June 28, 2010—not for torture, but for obstruction of justice and perjury, with a prison term of less than five years. This was almost forty years after the first known act of torture under his watch in 1973. The sentence pales in comparison to the decades that many of his targets spent in jail, often as a result of convictions based solely on confessions Burge and his detectives had tortured out of them.

It also resulted in the historic reparations ordinance passed by Chicago’s City Council in May 2015, one of the first reparations measures implemented by an American city. It guaranteed a pool of $5.5 million in monetary compensation for torture survivors, free education at any City College, and counselling for survivors and their families. In addition, it includes a curriculum about police torture in Chicago Public Schools, a public monument the city has yet to build, and the creation of a torture justice center on the city’s South Side.

Aislinn Pulley, co-director of the center and an organizer with Black Lives Matter Chicago, praised the Alliance’s efforts around police torture, saying that organizers from the Alliance were part of the torture justice movement from the beginning. Survivors of police torture in Chicago, both under Burge and after his tenure, were also at the conference to share their stories.

In Chicago, the Alliance extended support beyond Black movements to others in the city. The conference’s structure reflected these relationships through the visible presence of international movement leaders at the rally and throughout the weekend. When Palestinian-American organizer Rasmea Odeh faced the stripping of her American citizenship and deportation to Jordan in 2017, Chicago Alliance members joined Palestinians in supporting her. In a video message, Odeh spoke from her home in Jordan and personally thanked the Alliance, co-chair and educational director Frank Chapman, and Angela Davis.

Giving the rally’s keynote speech, Davis emphasized that, from its founding, the movement was dedicated to a multiracial and internationalist struggle against repression, telling the audience that the American Indian, Chicano, Puerto Rican nationalist and other movements were integral to its character. “We were very insistent on the multiracial character of the organization and recognized that we could not move forward in the struggle against racism without acknowledging the importance of white people learning to accept Black and Brown leadership,” she said. As the rally and conference continued, the diversity of the attendees and workshops themselves seemed to act as a blueprint for the intersectional, radical internationalist movement that NAARPR originally embodied, and that the refounded NAARPR seeks to recreate.

Palestinian-American organizer Hatem Abudayyeh took the stage on Friday to rustle up funds for the fledgling Alliance, and as he called out bids for donations like a leftist auctioneer, hands shot up across the packed hall to put up cash for the movement. Funds poured in from Chicago and national organizations and, as the internationalist rallying cry went that evening, “from Palestine to the Philippines.”

Bassem Kawar, an organizer with the Arab-American Action Network and the US Palestinian Community Network, spoke with the Weekly after the Friday rally about the internationalist dimension of the movement.

“We’re part of the Chicago Alliance’s steering committee and have organized shoulder to shoulder with them for a long time,” he said. “What you saw in there was a multinational, working-class room, and it’s hard to find rooms like that [anywhere else in] the country.”

“It all goes back to the historic ties between ours and the Black communities in Chicago. If we could date it back to the Washington days with the Rainbow Coalition, the Palestinian community played a major role,” Kawar said. “Most recently, in the movement for justice for Laquan McDonald, we were shoulder to shoulder with the Alliance since day one, at the Black Friday Boycott… and to be real the Alliance has always supported Palestinian liberation work here in Chicago. I was one of the lead organizers for Rasmea’s defense work, and the Alliance was with us since day one…Our solidarity isn’t transactional—we have the same ideology and the same aims.”

Intersections and discussions between these communities made the conference itself a generative space—one that in and of itself served as a model for the movement it was seeking to create. A workshop on civilian, democratic control of the police saw attendees break up into small groups to talk about how they’d push for and implement CPAC-like structures in their own communities. Attendees from around the country discussed how the Chicago model was being replicated in cities like Jacksonville, Florida, and Minneapolis, and ways to keep these movements connected. Another workshop on centering families in the movement for accountability for police violence gave the floor to family members themselves to speak out about what it was like to lose their loved ones to unjust violence.

Martinez Sutton, the brother of Rekia Boyd, was one of the speakers at this workshop. Alongside him was Rekia’s sister, Kenyatta Rosemond, who spoke publicly about Rekia for the first time there. She spoke, haltingly, of what Boyd’s killing had done to her mentally, emotionally, and even physically.

“I’ve been in anger management for four years,” Rosemond said. “I’m very upset, and I haven’t cried. I haven’t cried.”

“Rekia was my baby,” she said after a long pause. “She used to lay on my chest.”

“I was stopped by the police officer three weeks ago on Ashton Street going to the VA and I just freaked out. My cousin literally had to pull me out the car and hold me, ‘cause I wouldn’t raise my window down to police.”

“Police officers are the worst thing that triggers me… So I just wanted to see if I could get up and talk and I guess I can.”

Toshira Garraway, the fiancée of Justin Teigen, followed her. Teigen’s badly bruised dead body was found in a recycling facility in St. Paul ten years ago. Garraway says that the St. Paul police beat Teigen the night before and threw his body in a recycling bin, where it was picked up and taken all the way to the processing facility before being found. That was in 2009, four years before Black Lives Matter was founded, and she described the isolation of trying to push for accountability in the absence of a robust organizing community.

“[The police] want you to fade off into the background, and they want you to be silent….I was scared for my own life. [But]…I cannot continue to hear this stuff and, and just know that they’re doing this to our people and just be silent about it…. The reason that they’re able to continue these murders is because they’ve been able to isolate the families one by one.”

“But we’re able to come together ‘cause it’s like, ‘Oh that happened to your family. That happened to my family.’… There’s strength in numbers. So that’s why I’m glad we’re doing this, to come out with these stories so they cannot pick us off one by one,” Garraway said.

Martinez Sutton told me after the workshop that he felt the success or failure of a refounded National Alliance would depend largely on whether its movement can stay internally coherent, and whether it can decide on an effective organizational strategy. Part of the struggle, for him, was whether the movement could balance system-level demands with achievable, short-term results.

“For me, a lot of people here are advocating to take down the whole of CPD, but that’s so hard,” he said. “Why don’t we learn from how they target us? Why don’t we pick them off, one by one, remaining as much of a thorn in their side as possible? We can focus on one killer cop, get him convicted, force him out of CPD. Like that, bit by bit, once you chip away at the building, you’ll eventually get to that foundational stone that’s holding everything together.”

The idea Sutton was referencing—the eventual abolition of prisons and police departments—was a key focus of the conference. Discussing this tension between immediate, reform-minded measures like increasing community control of the police versus explicitly abolitionist ones, Chicago Alliance organizer Brian Ragsdale explained, “We often look at these two concepts as within a binary and…it doesn’t have to be either-or. We can advance the struggle for community control of the police while we then begin to develop ‘alternative ways of harm reduction,’ as Angela [Davis] described it.”

Ragsdale added that he didn’t believe the concept of abolition is immediately viable, but is part of a longer, transformative process—and argued that part of that process is making sure that police officers who have committed crimes under the present system would not be let off the hook. “I see almost no need for the police, but right now, we’re not at that place” Ragsdale said. “I’ve developed a lot of relationships with the family members, and I can’t go up to Armanda Shackelford and say, ‘Well, let’s have a conversation about what it looks like without the police,’ because that would be insulting…because we are living in a present moment where the reality is that their loved ones are in the prison system right now or have been tortured right now. So while part of me wants to vision a restorative justice place that I think we can get to, I want police who engage in these activities to be held accountable…they should not be outside the law at all.”

Jazmine Salas, the Chicago Alliance co-chair, described the progress she says allied movements have made in just a few years. “Refounding NAARPR is really…aligning for the first time the movements that are working on community control of the police. So when we started our campaign in 2012, there were … 150 people in a room. And since then we’ve grown to 60,000 supporters, and that’s just in Chicago. And we know that other cities are looking to us… And there are other cities who are launching campaigns using the CPAC model for community control of the police. So what NAARPR will do is it’ll give us the framework, especially a national framework for us to all synchronize and work together and learn from each other.”

The original National Alliance formed out of collective efforts to free Angela Davis after she’d been arrested and imprisoned on suspicion of involvement in a shooting at a Marin County, California courthouse in 1970.

As Davis explained in her keynote speech on Friday, “From the time I was first arrested in New York and held in the women’s house of detention in Greenwich Village, I could look around and see countless numbers of women who did not have the kind of support that I did. I felt that as long as the campaign focused exclusively on me, we would not be fulfilling our revolutionary mandate. And I could not myself feel comfortable being the sole beneficiary of this phenomenal campaign.”

After her input, the campaign changed its name from “The National United Committee to Free Angela Davis” to the same title, but with the addition of “And All Political Prisoners.”

True to its name, the movement, through a combination of nationwide and even international pressure, as well as funding from groups as disparate as trade unions and communist parties, the Presbyterian Church, and even college fraternities and sororities, pooled resources and succeeded in freeing Davis in 1972, when she was formally acquitted of all charges.

After achieving this and other initial victories, in 1973, the organizers turned the infrastructure they had created into NAARPR, an organization dedicated to protecting emerging minority-led, left-wing movements in the United States from law enforcement and federal targeting, as well as fighting for individual prisoners facing unjust detention.

According to Salas, at the old National Alliance’s height in the ’70s and ’80s, it boasted twenty-six chapters nationwide. She mentioned that this number dropped steadily as programs like the FBI’s COINTELPRO surveilled, divided, and violently targeted Black, Brown, and left-wing movements such as the Black Panthers.

The conditions that ultimately led to the decline of the movement, according to CAARPR organizers, are still active today. Salas listed the urgency of addressing police killings, the targeting of movements like Black Lives Matter by the FBI under the label of “Black identity extremism,” and a rise in nationalist violence worldwide as the stakes that inform the movement’s refounding.

Though the movement dwindled, it “didn’t die out,” Salas said. “Considering all of these things, it’s kind of the perfect time to really get it going again. Applying these lessons that we’ve learned as well as trying to basically protect people’s rights. Because we are losing our rights every single day.”

Back on opening night, Pulley referenced the idea that a newly refounded NAARPR could represent the alignment of local and national movements through the example of torture justice in Chicago, arguing that torture remains a part of Chicago police operations at places like its secretive Homan Square facility in North Lawndale.

“When they talk about the ‘Era of Burge,’ don’t let them use that language, because the torture continues to happen…The work we have to do is to end torture completely in this city and across this country,” she said. “And what that means is that we have to free all the prisoners, we have to open all the cages, and we have to defund all the police departments.”

Moving forward, on the conference’s last day, members voted to establish the foundational layers of the movement. At a closing rally, they elected longtime Chicago Alliance organizer Frank Chapman as interim Executive Director, and chose to establish a continuations committee to pave the way for the organization to start connecting movements nationwide.

Anna Luy Tan contributed reporting.

Ashish Valentine is a Chicago-based audio and print journalist. This is his first piece for the Weekly, but you can find his work at WBEZ, NPR, and subtitle magazine.

Hi, I’m a high school junior at Lane Tech. I’m interested in politics and creating better public policy so I’m looking to help an organization that deals with this through an unpaid internship or other work/projects. I enjoy writing and research. I’m a writing tutor at school. Tech is my other interest because CS can be applied to anything, but I would like to do something related to politics if possible. Thank you!