Turtle wax!” someone yells. A scraggly mustache twitches while reading aloud ads from Life Magazine. Snippets from a staticky radio intercut the hubbub. “You’re listening to Art and Artists with Harry Bouras—” begins the clipped voice, emanating in jagged lines from the radio.

“Harry who?” Karl Wirsum interrupts.

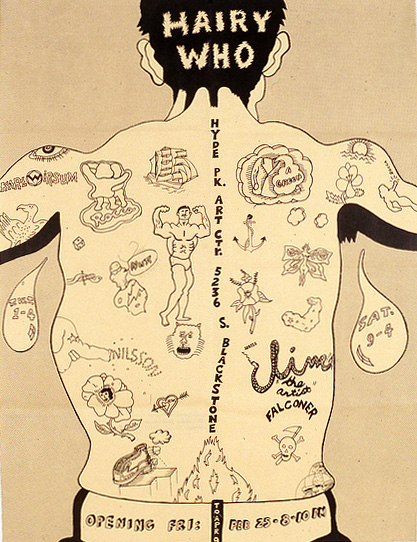

A sudden silence—a collective gasp from his fellow artists—and “HAIRY WHO,” drawn in a font that can only be described as fuzzy, bursts from the Chicago apartment buildings in a triumphant boom.

This black-and-white animated sequence from the documentary “Hairy Who & the Chicago Imagists,” screened last Friday at the Logan Center for the Arts, answers the question of where the Hairy Who name came from, but the question in the name itself remains: who are they? Or, as narrator Cheryl Lynn Bruce asks when discussing the Chicago Imagist movement’s fall from fame and favor: “Hairy Who?”

The question is valid. Sure, there are answers rife with word association: the sixties! The Second City’s version of Pop Art! Colorful, lewd, full of insanity and grotesquerie and sexuality! But beyond the confidence, simplification, and occasional falsity of these exclamations, no one seems able to truly answer the question, not even the artists. The documentary doesn’t even try. Bruce’s remark at the beginning—“a group of artists shared a moment in Chicago”—is as close as it gets, though, she adds, it’s “not a story about Chicago.” That nebulousness is part of what defines the Hairy Who and all the Chicago Imagists.

Appropriately, the documentary presents not one straightforward storyline but a web of influences, teachers, galleries, and people to explain these loosely affiliated, manifesto-less artists. We jump from the Maxwell Street flea market to cartoons, from gender to Surrealism. The viewer is invited to fill in the web’s latticework, but a solid web is ruined and stationary. The Imagists, if they were anything, were all about movement.

“Hairy Who & the Chicago Imagists” successfully captures that giddy energy. Archival footage abounds, old photographs and newspaper headlines vibrate, irrepressible animation creeps in at the frame. Even the art looks like it can’t stay still. “In those early cartoons, everything moved,” says Hairy Who artist Gladys Nilsson as the limbs of Popeye characters bounce, followed in the next shot by her paintings of intertwined limbs. She might as well be talking about herself and her compatriots.

Witness how another artist, Barbara Rossi, gives Olive Oyl a run for her money with the twists and turns she unleashes in just a few sentences: “I like the contradiction of using feathers and plexiglass…and hair. It was a new way of making line. I didn’t think it could only be defined as feminist art. I feel like I’ve gone through my life on my eyeballs. I just keep rolling along on my eyeballs, and I don’t know how else to do it.” She smiles, wide-eyed. She’s not sure where she’s going; she only cares that she goes.

Jim Falconer compliments the film’s constant motion at the post-screening panel discussion. He would know: he exhibited at the first Hairy Who show at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1966, as well as the third and last one in 1968.

“It has an energy of the time,” he says. “It’s almost in the editing, you know, the nervous twisted connections and disassociations, and things associate and disassociate again. There’s a kind of hesitancy to commit to what a thing is, what an Imagist is.”

Note the dropping of “Chicago” there: just Imagist. Hesitation to commit to the movement’s Chicago roots recurs throughout the film too, voiced by several interviewees and crystallized near the end by Art Institute Curator James Rondeau. “The Imagists should be and need to be contextualized within a much broader spectrum of Pop Art internationally,” he says. “The humor, the grotesque, the ribald, the caricature, the overt sexuality, the potency of that, transcends the limits of a Chicago story.”

But neither the panel nor the audience can stay away from Chicago. Moderator and University of Chicago professor Rebecca Zorach wonders what happens to the story of avant-garde art when Chicago is at the center instead of the periphery. Panelist Richard Born, the Smart Museum’s Chief Curator, remembers that when he moved to Hyde Park in the seventies, his landlord was Imagist Roger Brown. Falconer reminisces about the “great party house” in Kenwood that belonged to Don Baum, the Hyde Park Art Center curator who first brought together all the artists for those group exhibitions.

When a man in the front row with a bandage on his forehead turns out to be the printer of the Hairy Who comic books the artists made for their HPAC shows, it’s clear we’re stuck in this town. Falconer may have decamped to New York when he was twenty, but he’s the most excited he’s been yet. “People have been looking for you for years,” he interrupts. They try to figure out whether the printer—Tom Brand—sold several proofs to Falconer’s friends thirtyish years ago, and go backward from there. Was Falconer among the artists Brand trained in printing? Did they go to the same outsider art show on Clark Street—near the Century Theatre or the Ivanhoe? Once they begin haggling over the art’s pricing, Born switches the subject to rescue the discussion from hyper-locality.

You can’t escape Chicago that easily. Falconer liked Hyde Park because the people he met there expanded his perceptions, he tells me at the reception after the panel, mid-brownie-chew.

He’s just told me he moved to New York for the same reason, so he could learn even more instead of being defined by the Hairy Who and Chicago—“I had to make mistakes, make more mistakes, make bigger mistakes. My life’s been a continual mistake”—when Brand returns. They slip easily into the sort of conversation that involves name-dropping street corners.

Falconer may have moved to New York, but a few years ago he moved back to Chicago, and now here he was, anchored like the Imagists were years before by this city. In one of those Hairy Who comic books Brand printed, the final line of dialogue was, “I DON’T BELIEVE in Hairy Who! / Neither do I!” Believe in them: although the web has disintegrated, the artists are still here, and still moving.