Back in February, everyone at Project Onward’s studio shifted from their workstations and huddled for a group meeting to discuss the novel coronavirus possibly appearing in the United States. Then, the details of COVID-19 were highly unknown, but the disability arts organization’s artists and staff tried to address the uncertainty of what might come.

Some artists, wishing for the best, hoped that the Bridgeport studio, open for sixteen years, wouldn’t shut down, even if the artists had access to materials at home. Half a year later, the studio’s workstations have long been still, but its artistic capacity is far from that.

As a studio and gallery space, Project Onward’s mission is to support the emotional wellbeing and growth of professional artists with developmental disabilities and mental health needs, through free artist-in-residence and art entrepreneurship programs. Project Onward not only addresses professional barriers its often marginalized members face to work in artistic fields, but it also removes cost barriers for artists who are low income. Each member artist is given studio access with gallery space, art supplies to maintain their unique portfolios, and individualized mentorship. With what Project Onward describes as their “visual voice[s],” member artists are destigmatizing mental illness and developmental disabilities—and during a global pandemic, they are also building an online community by developing programming to approach and reflect with artists.

With a staff of five, this nonprofit has kept going to support its fifty artists. The studio has curated several online exhibitions, events, and weekly artist highlights while navigating the stress of keeping their virtual doors open. Project Onward transitioned from global uncertainty to micro-consistency by centering artists’ presence and the connections between art and life in virtual spaces.

In the introduction to its current “Cause and Affect” exhibition, the studio stated, “Project Onward has a distinct relationship to the events of 2020. The neurodiverse nature of our artist community greatly impacts their perceptions of and responses to national and global crises….Our artists have chosen to document and comment on both the extremity of what has passed this year and what they hope the rest of the year can bring.”

“[There is a] love to make artwork and the need to make artwork and to show people how talented these artists are….Their work is just as great as anything on the commercial level of art today or fine arts in Chicago,” said Robyn Jablonski, Project Onward’s studio manager for the past nine years.

When visiting the studio before COVID-19, you could see workstations or “cubbies” that mirrored each artist’s unique and contrasting styles, like Elizabeth Barren’s glamorous mixed media and Blake Lenoir’s zigzagged color pencils on their desks. There was Sereno Wilson pouring cascading amounts of green glitter, and Fernando Ramirez holding sharp eye contact with his ongoing piece, and Julius Bautista painting in an electric realist style. You might also have met Ryan Tepich in the kitchen; Safiya Hameed, known as the “Princess of Project Onward”; or Franklin Armstrong, described as “our news man” for his penchant for sharing the daily news, walking along the busy studio space. Together, the artists were tracing knowledge through artistic windows connecting their world to others. From the compassionate exchange of ideas between artists asking for advice from their studio neighbors to laughter from conversations, Project Onward’s not just facilitating the production of art—it’s also building a community.

Many of the artists are self-taught, and they have come to Project Onward from a multitude of lived experiences. Before joining Project Onward in 2008, Tony Davis sold drawings outside Union Station that interpreted “his own life” in the Chicago Housing Authority’s ABLA Homes development on the West Side. Some artists have known each other their entire lives, like the Juguilon brothers, or grammar school best friends David Holt and Jackie Cousins Oliva.

Many artists have also maintained a partnership/life journey with art that started in their youth, as a way of processing their experiences. “I started drawing because I didn’t know how to say what I thought. I was only three years old, and the blue ink pen was the only thing I could find after a traumatic event,” said Keturah Lynn in her artist bio.

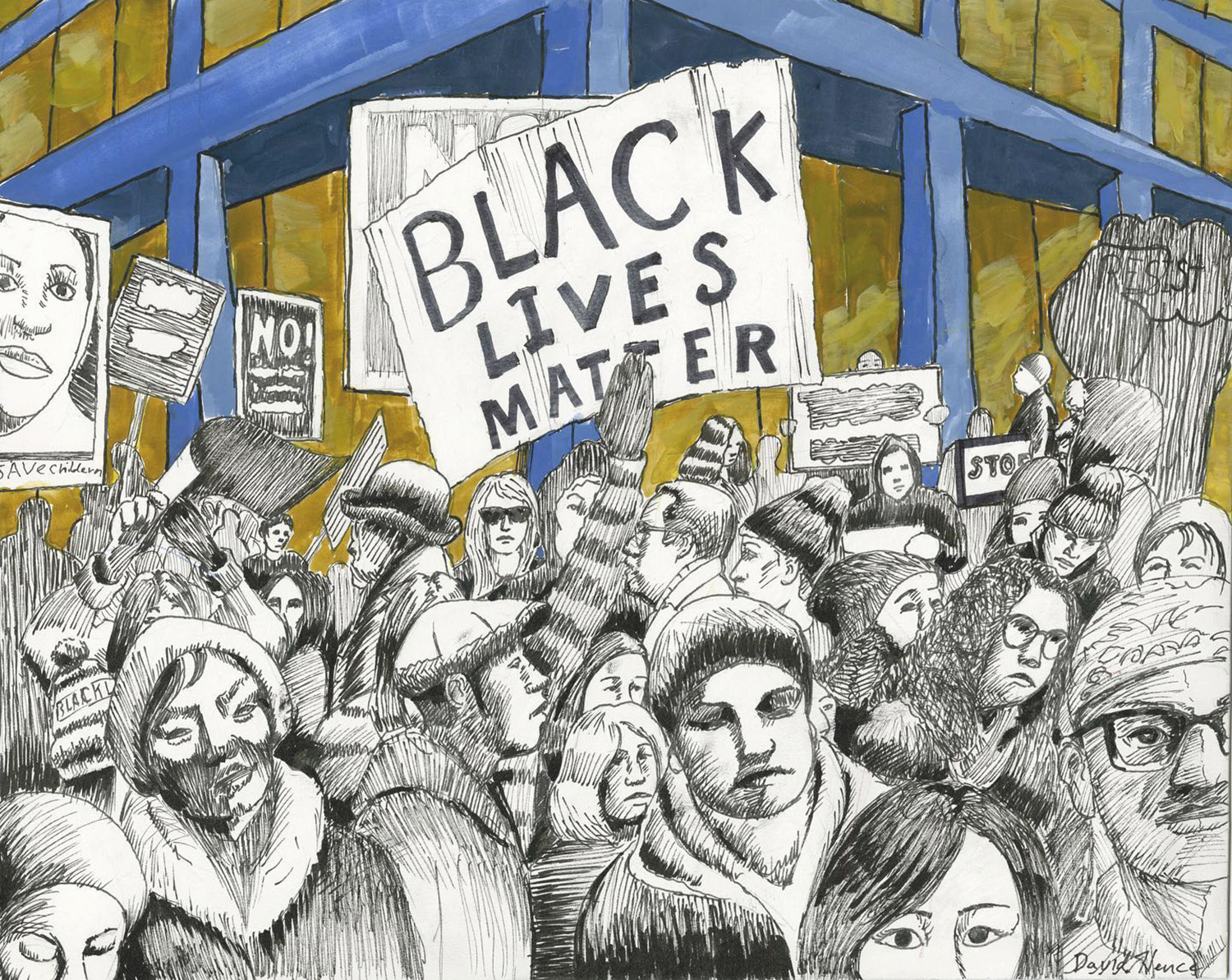

David Hence said, “I don’t mind sharing my sketchbook because I think it’s my way to express myself….It helps me be in the moment.”

Other artists, like Paul Kowalewski and Allen McNair, describe art as more like its own being, composed from their thoughts or dreams. “I’ll start something, and it won’t necessarily end up the way I was thinking. It takes on a life of its own,” said Kowalewski.

As a community, Project Onward reinforces an artist’s individual affinities and helps them have collective impact. The artists’ backgrounds and studio relationships work together to encourage passionate direction in affirming bold paths.

Art made by artists with minimal or no training is often labeled as “outsider art” due to its distance from the mainstream art world and its institutions. As a term, “outsider artist” is understood as positively reflecting an individual with multifaceted potential but without formal artistic training. But this term also risks marginalizing artists who lack institutional privilege. Project Onward artists navigate this tension as both an opportunity to address exclusion and to expand distinction.

“Project Onward looks to question, if not always answer, and challenge what the next step in this genre of art will be moving forward. We mean to open a visual dialogue with the viewer in hopes that more questions and curiosity about these forms of art emerge,” said Project Onward Executive Director Nancy Gomez at the nonprofit’s “Outsider Connections” virtual panel discussion in June.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

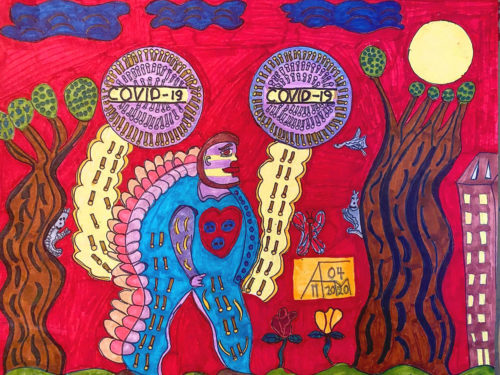

Artists are not waiting for an external answer. Many are leading their own outsider art narratives through their work—most envisioning possibilities by looking inward during the global pandemic. In Project Onward’s weekly “Artists at Home” interview program (started during the pandemic), many have talked about their individual perspectives. In his interview, Dijon Barrett described a current unfinished piece as imagining “what’s going to happen after the pandemic”; artist Luke Shemroske similarly talked about how his “Virus in the street” piece highlights how artists are uniquely witnessing the pandemic in their own lives.

“Sometimes, in some pieces, I’m just working things out, for myself…and to allow other people to have a glimpse into how some of those things feel for me and for people in similar situations,” said Cherylle Booker during her artist interview.

Project Onward artists like Barrett, Shemroske, and Booker are expanding artistic recognition for neurodiversity. They do so across artistic realms and through worlds that orbit each other to collectively shape a universe of meanings and possibilities.

In “Cause and Affect,” the artists provided a portal to cross virtual bridges to “still question, hope, believe and fight for a more just, peaceful, and healing nation and world.” Paintings range from “Christopher Columbus Takedown” by Janno Juguilon, to Molly McGrath’s self-portrait “Trying to Fight Covid-19” and Alfred Banks’s “Black Girls Rock,” reflecting struggles and transformations.

In this and earlier online exhibitions, one can see the extent of Project Onward’s engagement and creativity in these past months alone. “Repeat Repeat Repeat” explored the spectrum of responses to repetition as either a meditative process to create predictable outcomes or as an “act of compulsion”; “Wild and Beautiful” asked audiences sheltering at home to imagine “things beyond our four walls.”

“We should appreciate those other points of view or other visions of the world, especially as far as the aesthetic of the artwork. Nothing has to fit a particular mold,” said Jablonski.

Despite success and growth, challenges remain for Project Onward; a particular concern has been how to stay connected with artists during the pandemic despite the digital divide for communities with developmental disabilities. “No wifi. No Internet. No smartphone,” said artist Ricky Willis during a recent interview with NBC 5 Chicago. For Michael Hopkins, his difficulty is not simply missing tools but lacking the familiarity to use the ones he has. In the NBC story, when asked about his computer, he said, “I don’t know how to work it, no way.” Currently, Project Onward hopes to distribute technology to more of its artists through an arrangement with Apple.

As Project Onward works to support artists without access to technology, they are also addressing social isolation. In July, the team started weekly group calls where, as staff said in a Facebook post, “Everyone was so happy and excited to see each other’s face and catch up.”

The overnight switch to remote programming symbolically marks Project Onward’s second location change as an organization after moving out of its original location and into Bridgeport Art Center during 2013.

To prepare for this physical relocation, Jablonski joined Project Onward to support artists to adjust to this new environment and help artists who experienced additional challenges. Her background in behavioral health supported relationship building through mutual understanding and supportive environments for the past seven years. Now as then, as an organization, supportive relationships and a safe environment have kept Project Onward going during uncertainty.

“It’s funny because you’re not just in a straight path, going forward all the time, right?” Jablonski said in February. “It’s called Project Onward, but you’re not going in a straight path….it’s change you cannot predict.”

Now, in 2020, Project Onward is working with artists within their homes to craft a new beginning from years of strong foundations. And the participating artists continue to creatively interpret the overwhelming disorientation of the past six months to build their artistic worlds.

The full list of Project Onward’s artists and their biographies are available on Project Onward’s website. Artworks are also available to purchase to support artists and maintain high-quality art supplies. For more on Project Onward, such as donating, volunteering, or purchasing artwork, please visit projectonward.org

“Update 9/18/20: A previous version of this story misspelled the name of Cherylle Booker. The Weekly regrets the error.”

Jocelyn Vega is a first-generation Latina. She is a contributing editor at the Weekly and last wrote about the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless’s census advocacy.