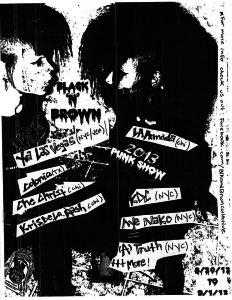

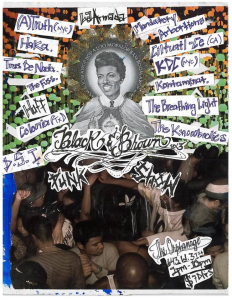

Monika Estrella Negra and Donté Smith started the Black and Brown Punk Collective in 2009 as a coalition of activists and musicians dedicated to building a more inclusive scene for Chicago’s underground shows. The collective operates under a DIY (“do it yourself”) organizing ethic, promoting solidarity between minority groups in a segregated city and carving out a space for queer, trans, and intersex people of color (QTIPOC) in a punk scene that is overwhelmingly white and male. Along with a near-annual summer festival, Black and Brown organizes a year-round series of workshops and fundraisers to benefit groups like Feed the People, a grassroots food bank based in Chatham, and The Anhelo Project, which awards college scholarships to undocumented students. The fifth Black and Brown Punk Show is set for the weekend of August 28. This year’s program will focus on the eradication of anti-black racism and hate crimes against black trans women, and it will benefit Sojourners Land, which organizes rural retreats for the QTIPOC community, and a New Orleans group with a similar project. Monika and Donté will also be presenting on DIY sustainability and how to make a mixtape in June at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit. The pair took an afternoon last week, Donté calling in from the middle of a New Orleans hailstorm, to talk to the Weekly about queer chosen families, punk gentrification, and salvaging the Chicago scene.

What was the need you saw in the Chicago punk scene when you started Black and Brown?

Donté Smith: It came from seeing black and brown kids who were at shows together and weren’t organizing events or making space for themselves. It’s all about representation, and seeing communities and groups of folks that aren’t connected. The Chicago punk scene definitely has some boys’ club dynamics, so I think it was wanting to address that and change it—to show folks that there can be an inclusive scene that isn’t oppressive or patriarchal.

Monika Estrella Negra: Even though there is a legacy of Latino punk, there’s still a lack of visibility for people who are othered. That goes for black punks, Asian punks, Southeast Asian punks—it transcends ethnic identity to include things like gender identity, sexual orientation, people who are differently abled.

How do you relate to Fed Up Fest, Chicago’s queercore festival?

MN: Fed Up Fest and Black and Brown have been doing cooperative fundraising, but one of the differences is that their participants are largely white queer and trans folks. A certain stigma that comes with being queer or being a person of color is that you can only be either/or, and it’s too complicated to jumble all these other identities into it. That’s always been a part of Black and Brown, saying, “We know you can be all of these things.” We’re reacting to a more homogenous queer scene.

Can you tell me more about how Black and Brown functions as a collective?

DS: The collective thing comes from our background as anarchists. I’ve been involved in leftist social justice movements—anti-war, anti-militarism, queer and trans liberation, labor rights, food justice—for the past ten years. We’re working together because we’re friends and we support each other. It’s not like some old-school anarchist place where we all sit in a room together and vote and reach consensus every time.

How do friendship and kinship work into what you’re trying to do?

MN: Because we both come from a pretty strong QTIPOC community, chosen family is very important. That means we get into arguments, but we’re all committed to each other and to trying to work it out. That’s very important. There will be constant ups and downs, but there will always be a strong line of solidarity and reliance on each other.

DS: Being queer folks, gender-variant folks, and folks of color, we get to create our families; we’re not bound by biological families. We get to choose what our relationships are to people, whether this person is my sibling or bestie or cousin or mama. We get to create that. It’s something we’ve had for such a long time, it’s part of our culture. You think about Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson [founders of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, which operated a home for queer homeless youth and sex workers in the 1970s]—STAR was a created family. It was also something born out of Stonewall [a series of demonstrations in 1969 in reaction to a police raid of the Stonewall Inn, commonly considered a turning point in the gay liberation movement]. These families have always been the way that we protect each other. It’s about creating our own intentional spaces, to protect ourselves against a world that wants to kill us.

This is obviously a political project as much as it is a musical one. Why punk? Why the punk scene?

DS: Punk music is an institution now. They show that shit at the Met [referring to the 2013 “PUNK: Chaos to Couture” show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art]. Designers use the punk aesthetic for worldwide appeal. As with almost all institutions on this planet, there are dudes in power who are making money off of artists, promotions, events, shows, off of their connections and the venues that they control. That continues into the way the scene exists in Chicago.

MN: Aesthetically speaking, punk has been whitewashed in so many ways. The word “punk” itself has a different definition for whatever scene you’re rolling with in this city. Black and Brown is constantly trying to redefine punk as being about survivalism and DIY culture, which are imperative if you’re a marginalized person in this country. It’s the stuff my mom and my grandmothers did. It wasn’t punk in the idea of that subcultural identity, but everything they did was DIY. And that to me is punk.

I grew up in a pretty poor family, and my mom worked three jobs. She was a single mother, and we didn’t necessarily have all the things that we needed. But because of a community taking care of each other, friends would babysit us when she had to work. That’s a survival skill: being able to support somebody who you don’t even know but who is in the same collective. Working with people in order to hold events, fundraising for something that will help something bigger—that’s always been Black and Brown’s impetus, even though we use the work “punk.” I love punk music, I hang out with other punks, but it’s always been about a way of life and not just my subcultural identity.

Is there a legacy of punk or underground in Chicago that you see yourselves as continuing?

MN: When I first came here, I started going to shows like ShyGirl Fest on the West Side. Martin [Sorrondeguy, vocalist for Los Crudos and Limp Wrist] was definitely influential to me in a lot of ways because of his identity as a queer man, but also as a brown man, growing up in Pilsen and having to go out and play punk shows with a lot of white kids who didn’t understand his identity.

DS: I was definitely inspired by the first bands I saw in Chicago, like Condenada, Bromance, and Sangre de Abajo—they’re all fronted by women and gender-variant folks of color, and the music is really political. That music inspired me to organize.

How does Chicago’s racial stratification affect the work Black and Brown is trying to do? How do you organize integrated shows in segregated communities?

MN: I believe that there needs to be sound solidarity between people of color in general. In Chicago there’s always been a major rift between black and brown people, but we have a common sense of struggle that traces back to the transatlantic slave trade, colonization, and imperialism. The way this oppressive system works is to pit minorities against each other; the distances between neighborhoods can be so large that sometimes the only times these kids interact is when they come to our shows.

DS: We play around with formats; we’ve done lots of versions of the punk show. We’ve done our shows in football arenas in Pilsen and youth arts centers in Uptown. Those are very different vibes. I’d also say that gentrification is an issue for us. A lot of the spaces are owned by white punks now who are opening their doors to us.

From your perspective, what’s the relationship between punk and gentrification?

MN: The whole process. The mainstream punk aesthetic is no different than any sort of subcultural group that has always and strategically been used as a buffer. Once that scene is created, it becomes a hotspot for realtors.

DS: You move the punks in because the punks are okay with being crusty and being in a neighborhood with black and brown people, so they move in first and then create a certain scene that brings in hipsters. And then boom: you’ve got a Forever 21 and a Starbucks in five years.

MN: The fact is, if you’re a white punk living in these gentrifying neighborhoods, you need to be proactive in giving back privileges and resources. One of the downsides of gentrification is that property values start to go up, things get more expensive, businesses start closing down, people start losing their homes. If you’re going to live in these communities, make sure you’re giving back one hundred and ten percent.

DS: I think it’s also about knowing the history of where you are and how your actions affect the neighborhood. You should know that the hip coffee place is actually shitty to their employees or calling the cops on neighborhood kids. Being in an area that’s being gentrified is being in a war zone, right? It’s a matter of understanding what the actual social war is like in that neighborhood, respecting that, and actively taking a role against being an accomplice in that war.

What does it mean to be a white ally in creating an integrated punk scene?

MN: I think I’ve pretty much gotten tired of trying to tell white people what they should do to not be fucked up. Just be observant. Pay attention, be receptive toward our blatant frustration and anger, and don’t write it off.

DS: Allyship is a verb. It’s about doing something. You don’t get to rest on your laurels and say, “Oh, I have five black friends, so I no longer have any anti-blackness that I have to deal with.” It’s a constant state of being. What does it mean to be in solidarity with someone and willing to stand with them? It’s that constant work that starts with the folks around you. Pay attention to the way your friends are frustrated by the scene, or the way they get treated at shows. Begin to ask why your friend’s band never gets booked. Are you paying attention to the dynamics of the scene? Which people are getting ostracized and mistreated?

Why do you think it’s worth reclaiming or repurposing punk, even after it’s been co-opted into a suburban white subculture?

MN: If you look at the history of rock and roll and punk, they came from a black style of music, and that’s the history of popular music in general. It was created by blacks, then re-recorded to play for a white audience. Some of the first punk bands to ever create the 1977 sound were all-black bands [referring to Detroit proto-punks Death and Pure Hell from Philadelphia]. That goes against the mainstream idea of what punk is, which is suburban kids rebelling against their parents while still having these privileges attached to them. There can’t just be one idea of what punk is, and we’re trying to create something that punk should be used for in order to help us support each other.

DS: It’s self-expression, right? It’s great, putting something magical together on a budget with some rags and pieces. It’s the anger and the emotion of the music.

What’s the role of anger in your work?

MN: I went to Ferguson last year, and it was a very collective moment of anger that I felt was very representative of all we’ve been expressing. We take all the violence and anger that’s directed toward us, and redirect it back into the faces of the oppressors. That was the whole ideology of punk: taking the frustration that you feel, all the pressures on your back from being born into this world, and thrusting it back in someone’s face. We’re saying, “We are black people. This is hundreds of years of transgenerational trauma and anger that has been building up.”

The Black and Brown Chicago Playlist

Picks from Monika Estrella Negra

1. La Armada – Negaciones

2. Bruised – Satisfying Texture

3. Boots – Amor de Lejos

4. Tensions – Snake Oil

5. Haki – Spliff

6. The Breathing Light – She Loved Everything

7. Ono – Albino

8. Crude Humor – Dancing Queen