For the wide-eyed artists at Redmoon, an experimental theater based in Pilsen, taking bold ideas to extremes seemed to be a guiding principle, whether or not it was practical to do so.

But you would also be hard pressed to find an artistic institution in the city of Chicago more committed to the practice of geographic outreach—or, for that matter, more willing to make community engagement a centerpiece of its mission—than Redmoon. Not only was the company based on the South Side, but the performances, workshops, and opportunities it provided reached as far south as Calumet Park and as far west as Lawndale.

And so it came with sadness, though not a great deal of surprise, when Redmoon announced on December 21 that it would close after twenty-five years of operation, vacating the 57,000 square-foot warehouse and performance hall it had rented since 2013. Redmoon’s years of success under the leadership of artistic directors Jim Lasko and Frank Maugeri were made all the more miraculous by its lack of a consistent cash flow; in a goodbye letter posted to its website, the company lamented that there existed no reliable funding model “for this civic and social artistic vision.”

The outdoor spectacles that Redmoon put on—“spectacle” was the only word that could describe them—were a mix of the odd and the fantastical, employing technically deft stagecraft to tell imaginative stories infused with mysticism. But with the acquisition of a large new space in 2013, the company began to pull their spectacles indoors, too. Descriptions capturing the controlled chaos these indoor shows often produced regularly appeared in the Weekly’s pages.

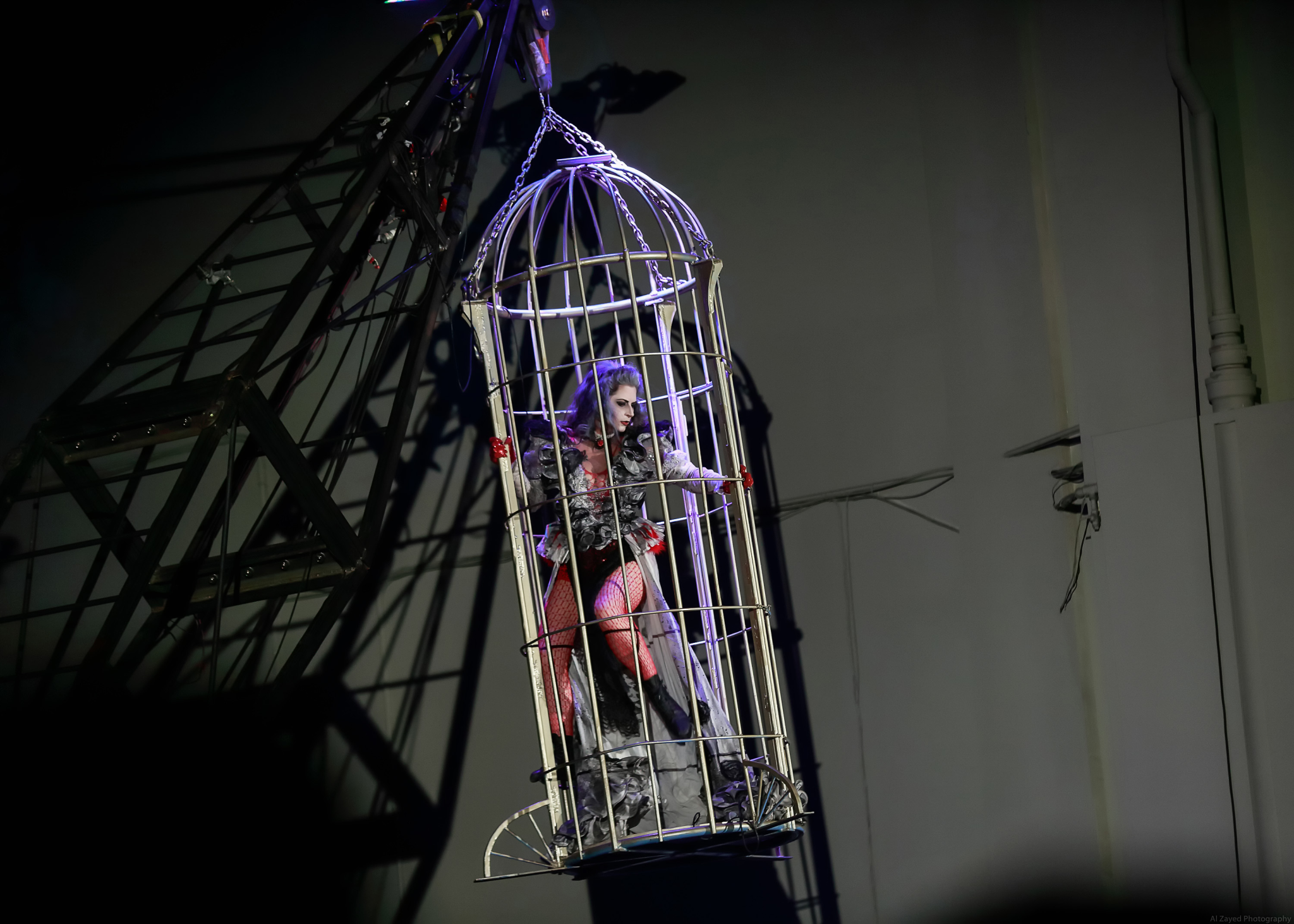

Redmoon’s offerings were diverse, showcasing performers and musicians from all over the city in performances at its space. Its annual Winter Pageant offered a strange, secular alternative to traditional mid-December celebrations. A Redmoon production this past spring, The Devil’s Cabaret, literally personified the seven deadly sins.

But taking its experimentation public, often in grandiose ways, was where Redmoon excelled. Lasko and Maugeri worked to bring their art to the public by physically moving it to the most public of spaces. The two were as conscious of space and place as any architect or urban planner, using heady vocabulary like “ephemeral placemaking” to describe their work.

“I love sitting in the silence of a theater,” Lasko once told the Harvard Graduate School of Design for a video it produced about his work with Redmoon. “It’s also a very socially tight sphere, meaning it’s a very narrow band of the public that cares about what happens in the theater space.”

In its drive to grow that narrow band, and because of the company’s eagerness to shoot for the stars, Redmoon ended up on the city’s biggest stages and in the public eye.

Its utter fearlessness could, and did, lead to failure. For all of the participation Redmoon elicited across the city in its 2014 “Great Chicago Fire Festival,” the city directed its rage at the company after the festival’s closing ceremony flopped. The faux houses it put to float in the middle of the Chicago River failed to light. It was theatrical disaster by any stretch of the imagination, enough to compel Lasko to write an apologetic op-ed in the Tribune days later.

In a remarkable comeback, Redmoon ran a second iteration of the festival the next year on Northerly Island. Filled with music, dance, and liveliness, it “made Northerly Island feel more like a village green in colonial New England than anyplace else,” the Weekly wrote. Redmoon’s willingness to consistently break the fourth wall of theater in jarring ways during the festival sometimes came off as tacky. Nevertheless, it was a product of the company’s commitment to creating theater for the people, no matter what it had to do to get them to pay attention.

But sometimes that meant stretching budgets, a reality that became clearer after the Reader reported how much the company owed its landlord in unpaid rent: $60,000. For all of the attention it paid to shared space, Redmoon was ultimately unable to maintain its own.

We Show Up With Big Machines (Bea Malsky)

At Redmoon Theater there is little separation between construction and performance; it’s an animal that willingly rolls over and offers up its mechanical underbelly, equal parts absurd and endearing.

[Frank Maugeri, Redmoon’s artistic director]: What we set out to do over the past four months, at sixteen different events, was to devise a machine—the Sonic Boom—that would be a platform for people in various neighborhoods. We’ve added onto it a bunch of our general aesthetic, so there’s drums all over it; it’s a parade item. It lifts up and down, and it shoots fire, and it’s a really wild machine. And that machine, alongside free drumming and poetry workshops for close to 100 people, would parade through neighborhoods.

Slow Burn (Stephen Urchick)

The Great Chicago Fire Festival was not intended to be brief and ephemeral. It was an exploration of a static trait. Redmoon trailers chugged tirelessly from Austin to Avondale, Englewood to Woodlawn, North Lawndale to South Shore in pursuit of this idea.

The riverbank crackled with applause as the engineer pushed himself up from his precarious fall and bowed off, ducking around the smoldering pontoon’s southwest corner. What Redmoon lacked in their trademark spectacle, misfortune repaid in dangerously genuine theater. The Fire Festival was reasserting itself as the human drama it’d been all along.

They trimmed their winding, rambling trek across town into a brief, glorious bite that—on account of a just little wetness—stuttered beneath hundreds of eager flashbulbs. Now that the smoke has settled, Redmoon’s own narrative more clearly reads as an effort to build relationships up, though they couldn’t burn their own houses down.

Ashes to Ashes (Will Cabaniss)

Redmoon took its unique brand of pop mysticism and grafted it onto the landscape of an entire island, creating a blaze that was nothing if not memorable.

For this year’s festival, Lasko’s company ventured out into the city once again, presenting performances and working with adults and children alike to build “community portraits” of eight neighborhoods, including Calumet Park, Little Village and Lawndale.

It was the “‘Great Chicago Fire Festival” in name only. The fire itself, an event in the city’s collective memory important enough to warrant its own six-pointed star on Chicago’s flag, served mostly to unite what was otherwise a scattered set of performances, speeches and, of course, conflagrations. The spectacle had little time for history.

Even more than unity, what emerged during the festival was the small-town persona that hides behind Chicago’s big-city sheen. To see thousands of people invested in a ritual intimately tied to the history of their hometown made Northerly Island feel more like a village green in colonial New England than anyplace else.

Give In to the Devil (Will Craft)

After fizzling at The Great Chicago Fire Festival in October, Redmoon has produced a triumphant success with The Devil’s Cabaret. The show is a truly interesting and fun spectacle—a return to classic Redmoon. The theater company has taken a simple concept, the cabaret, and transformed the experience into something far grander.

The simple conceit of the show belies the production’s sophistication—behind the sheer spectacle, The Devil’s Cabaret displays an impressive degree of technical mastery… As their motto promises, Redmoon quite literally engineers wonder.