[D]on Ross, an Englewood native, has been running a farmers market in the neighborhood for slightly over twenty-five years. Ross’s house and farm are on West Englewood Avenue, a little more than a block west of the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church. As I arrive, he steps eagerly out to greet me, and leads me around to the side of his house to his garden, an untilled plot of hard soil bordered by wood chips, about twenty feet by forty feet.

What do you grow here?

DR: Everything. Cucumbers, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, squash, and I have a peach tree in my yard, and it’s unbelievable. They say you can’t grow that stuff in the city…yes you can! And we have a permit to use the fire hydrant.

When did you start?

DR: I’ve been doing it off and on all my life. And you know we grow the stuff, give it away to people in the neighborhood, people will give us a dollar or whatever. We would take that to buy seeds with. And like I said, all the little kids got older, this and that, and they left me hanging. And I decided to just continue doing what I was doing, and I turned it into a farmers market.

Do you make any money off of this?

DR: I make a few pennies. Nothing big, big, big. I just like to help the community out and stuff. I believe I give away more than I make. But that’s how I am. I just do what I do, and I love it! Sometimes I get out here, man, and be here all night sometimes. It’s unbelievable, the stuff that I grow.

What was it like growing up here?

DR: People holler about Englewood, Englewood, but it’s bad all over. People talk about the games and stuff. It’s games around here, but like I said I been here all my life, who don’t I know? I don’t care where you go, it’s bad. I just mind my own business and here I am. I would never move, I’ve been here all my life. They can just bury me over in the garden someplace. When I leave they just bury me over here.

Ross goes inside his house and pulls out a stack of papers, his permits and licenses.

I’ve got all kinds of permits, and this and that. These are my permits to use the fire hydrant. When the police show up, they think you’re stealing water. This is a letter from the department of agriculture. I notarize things for senior citizens of the community. You see I don’t be playing with them. I’ve got everything.

Do you have another job too?

DR: At Chicago Public Schools. I’m something like an all-star. I do security, I help clean up. At 51st and Elizabeth, a school called Second Chance. It has kids, you know, they messed up in life. You know, pregnant girls and stuff, this and that. The age range is from sixteen to twenty-one. I’ve been working going on fourteen years now. You can say I teach, because I talk to the kids, try and mentor them, this and that. I don’t make no whole, whole, whole lots of money. Something else I do too, I get a couple kids from the community to help me over the summer. They make three or four hundred bucks, because I’m only up there three or four months out of the year. A little something to help them out.

Ross walks through his house, pointing to pictures of his now-grown nieces and nephews. On the back porch, he leans against the railing and points to a tree, a vanity license plate emblazoned with “The Dip” fastened to its trunk.

Now this right here is a peach tree. I planted that tree about eight years ago, maybe nine years ago. When I first turned that tree, for the first year or so it didn’t do nothing. Once it growed up, sometimes there’d be so many peaches on that tree it’d be pathetic. Sometimes I gotta take two by fours and prop it up, the peaches would be so heavy.

The peach tree is named The Dip?

DR: That’s my nickname. I don’t know where I got that from. It’s even on my card, see? It’s because back in the day my mom say I was always nosy, dipping in people’s business, this and that, so she named me Dippy. And people been calling me that sixty years now. Sometimes I think it’s my real name. I guess that’s where it came from. It’s the Rowan Trees Farmers Market, really, but I’m the only one who really do everything, so I just say it’s Dip’s.

Ross walks downstairs and half a block east along the street, where one of the other gardens stands. A “Rowan Trees Garden” sign is affixed to the fence in front of it.

Now this is another little spot. This just a little small garden. This is where we had our parties for our senior citizens, but all the people died over the years. The children growed up. These kids now, they don’t want to do nothing.

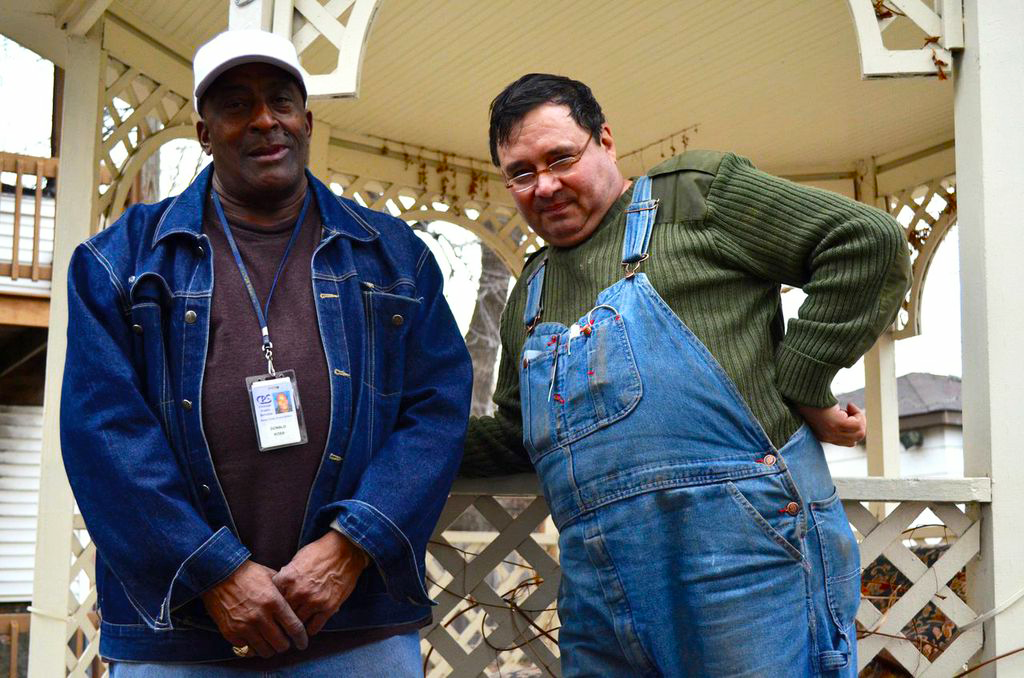

Another man, wearing overalls, walks out from an adjacent building.

DR: This is John Ellis, this is one of my partners.

JE: How’s it going?

We walk into the garden, mostly covered in grass and wood chips.

DR: I wish you could have seen this years ago. Tires, abandoned cars, condoms.

[To Ellis] How do you help out with the Rowan Trees garden site?

JE: Well, actually, it’s a long story. I started at a personal law firm downtown to help an old client who owned this hotel and all the buildings down here. He was a slumlord. He was a terrible client, and he was dying. He needed help, and it was something a lawyer couldn’t do. But I had experience working in prisons and as a nurse and all these other things. And they said, “John, go on down here and secure this place.” So I came down here and secured the front. And that’s when I met Dip and, to make a long story short, I decided to stay.

And at that point, I thought, I’m a person who knows how to do rehab and I can do that here. I also knew that lower-income people loved everything that yuppies did, I used to sit there in my wing-chair smoking on my pipe and I was very worried because all this horrendous stuff was around here. And so I dredged up my memory. I grew up in Montana, on a ranch, and so I knew something.

Then I decided I’d put grass here. We didn’t own anything, but we thought, we’ll just fence it in. Spend a thousand, fence it in. And we’ll plant grass. Anyway, then Dip came along and said, I want to do corn. I said, “Dip, if I let you do corn in that back lot, you can tie a mule to my back porch and I’ll never get any sleep at night.” We never spoke for five or six months. Anyway, we finally came to a resolution. We had huge raised beds from here to the back and from there to the back, and compost piles. And that’s when the old tale about everyone here’s from Arkansas or Mississippi really came home, because they’re here and they came over showing their kids what a compost pile was and what this was and so on. Just because they went down to Arkansas or Mississippi for summer doesn’t make ‘em haulers of water or drawers of wood. But the experience of being there and being around green things, they liked that. They really dug that. Ultimately, Dip started a farmers market which spun off from the original society.

Did he make a lot of money off the market in the beginning?

JE: Oh, good grief, I think the second year he was going it was something like $5000 in one summer. That was on farmer’s market coupons alone. He cleared $5000 out of the bank. I couldn’t believe it. I knew that some money was coming in. Yeah, it’s a money-maker.

Is it still a money-maker?

JE: Yes, it is. It could even be better. The problem that we’re running into right now, the city’s actually dropped regulations on a lot of the community gardens. Which they probably should, I don’t know that they’re all obviously appropriate. And frankly, the current administration has done us no good. We’re not getting any help from nobody.. We applied for a grant to get maybe $800 to help us get some liability insurance. The creeps over there, Teamwork Englewood and LISC, they couldn’t help us, ‘cause they had their own market. They gave them $35,000 to start a farmers market.

The city did?

JE: LISC.

Which is?

JE: Political patronage by other means.

LISC stands for Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a nation-wide nonprofit organization that aims to support community development.

It’s called Teamwork Englewood here, one of the new community programs. This is very poorly understood by the electorate of Chicago, but there’s an agency called LISC, it’s well-supported by the Ford Foundation, all of the corporations. And this is way the corporations take care of all the mayoralties in all the cities like Pittsburgh, Chicago. They give it to LISC, and [LISC] dish[es] it out. Anyway, they were supposed to help us, and of course they did not, because they had their own select freaks. So they went on for a couple of years. Smashing failure. Because they put their strawberry gelatos and everything else over there at the health clinic.

DR: People thought the church was doing all this [pointing to his own garden]. People would come down here: “I’m coming to get some of the church greens.” We would give it to ‘em. For years they thought it was the church. They got all kinds of praise. It was in the newspaper.

JE: The ministry does not live in these neighborhoods. They live out in Hazel Crest and everyplace else. Their congregants do too. They are here to get cheap rent, old cathedrals, and so on that they run, so they can run around and say that they are community leaders. Community leaders! And they ain’t. In fact, it was so bad, I can take you to Michelle down the street, and describe how one of the church functioners came out there with a gun, started walking around with a gun, started threatening her husband, told him to get out of the garden. Oh yeah! The church!

DR: And we get to barbecuing out there. We have firemen, police cars, they know we’re cooking. Even all of the gangbangers, but like I said, we know all of them. John knows just as many as I know.

JE: We’re all gangbangers! No, I mean, seriously, if you live in the neighborhood, everybody right here is BD [Black Disciples], go across Drexel all of them are GD [Gangster Disciples]. But that’s Chicago.

Ellis gestures across to the houses lining the opposite side of the street.

JE: That one’s empty. That has been empty and will be empty again, I’m sure. All these were abandoned. That one was abandoned. That is basically—well, it’s not abandoned, but it’s empty. So we just don’t have the oomph that we need for neighbors. We’ve got some, but I don’t know. It’s going to take a little bit more than that to keep this thing really going. In its heyday, it was really a heyday.

And good grief, we have no parks in this neighborhood. This place is relatively park-free. We did have a YMCA, but it was torn down years ago. We have one, but unfortunately it’s across gang lines. We also have seven aldermen within Englewood. In this neighborhood, it’s been so gerrymandered, you can’t possibly do anything. It’s divide-and-conquer. It’s gonna take a long time to correct this whole mess. The good feeling people should understand is people do understand these things. We’re out here, we’re doing it. Churches aren’t doing it, I can tell you that.

This garden is something, at least?

JE: Yeah. People identify with this because it’s them, it’s themselves, they know that. They don’t have to dress up fit to kill and put a gun in a holster and go into church. This is them. And the kids’ll understand it, too.

501 W. Englewood Ave. Saturday, May 9, 8am-3pm. Every Saturday. LINK accepted. (773)297-4766.