Glenn Harrell, seventy, was sitting in his South Shore apartment on a late Saturday afternoon enjoying his downtime from his job driving deliveries for DoorDash. Traversing Chicago in the driver’s seat has been a source of income for Harrell since 1973—when he started driving yellow cabs. Today Harrell also works as a limousine driver, door security officer, and a private investigator, and on Sundays he serves as Reverend for a small storefront church.

“I pretty much rip and run the streets all day doing one of the four,” he said.

Though Harrell initially supported former Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s candidacy in 2019, by the 2023 municipal election, he had switched his vote to current Mayor Brandon Johnson. “I like her—give credit where credit’s due, she did get a few things [done],” he clarified. “Her attitude is what kept her from doing more.”

Harrell was frank about his worries over increased crime in his neighborhood, where he’s lived for over thirty years. “South Shore has gone to the dogs,” he lamented. Last year, Harrell was carjacked. In Johnson, he sees a leader who may be more successful than Lightfoot was in improving public safety.

Harrell is among the forty-eight South Side residents who responded this May to a South Side Weekly survey that asked respondents to rank six of most memorable moments and themes of Lightfoot’s legacy–her responses to COVID-19, Black Lives Matter protests, the Chicago Teachers Union strike, Chicago Public School funding, the police union, concerns of public safety, her working relationship with City Council, and her media image. The survey was distributed via social media and a print edition of the Weekly.

For some, one hundred days into Johnson’s term, the energy of his victory has tempered into a cautiously optimistic assessment on his likelihood to deliver on all he promised. During this transitional period (the complexities of which we illustrated in this comic), we wanted to hear directly from South Siders about their expectations for Johnson, as shaped by their memory of Lightfoot.

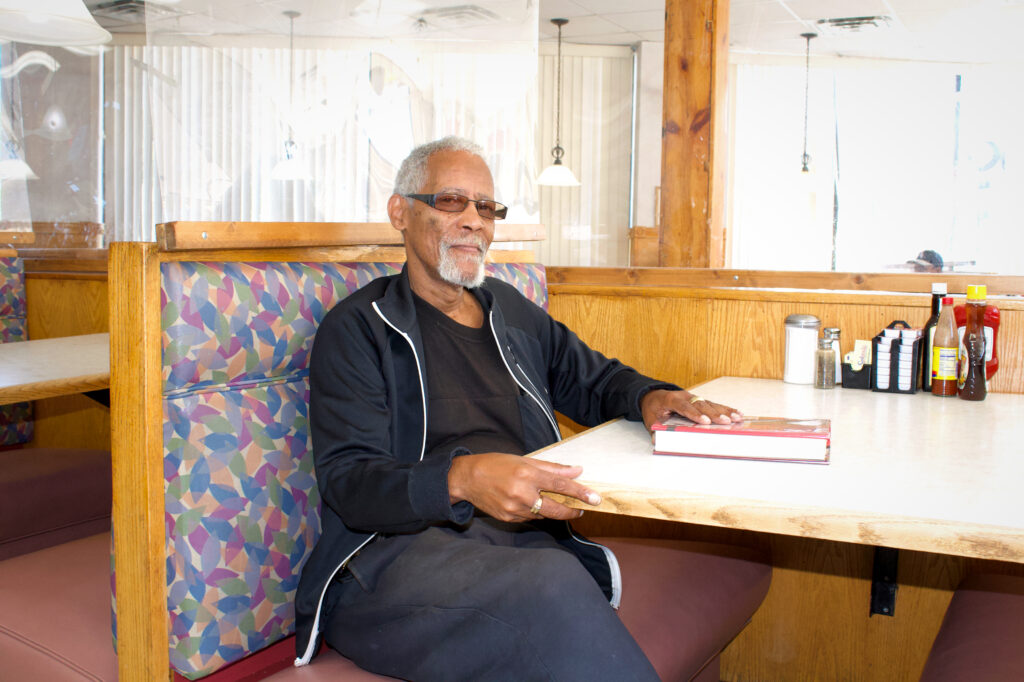

Since the pandemic, national and local headlines have trumpeted Lightfoot’s steep fall from grace, but they fail to capture why most Black South and West Side voters still supported her in her February re-election bid [VISUALS – SSW interactive map, Green = Lightfoot won this district]. Notably, in a lost race in which Lightfoot only cinched seventeen percent of the vote, precincts on the South and West sides were the only ones she earned a first-place finish.

Before the runoff in April 2023, pundits speculated about who would win over Lightfoot supporters in these majority-Black wards on the South and West sides. As it turned out, Johnson, too, can thank them for his victory: in April, majority-Black precincts delivered him around 88,000 more votes than he had in February, which ultimately vaulted Johnson past Vallas’ 60,000-plus vote lead in the general election.

What about Lightfoot’s four years garnered South Side voters’ support in 2023—a time when so many in other parts of Chicago were happy to see her booted out? In Johnson, which positive traits of Lightfoot’s tenure are South Siders hoping to see echoed? What approaches do they hope are different?

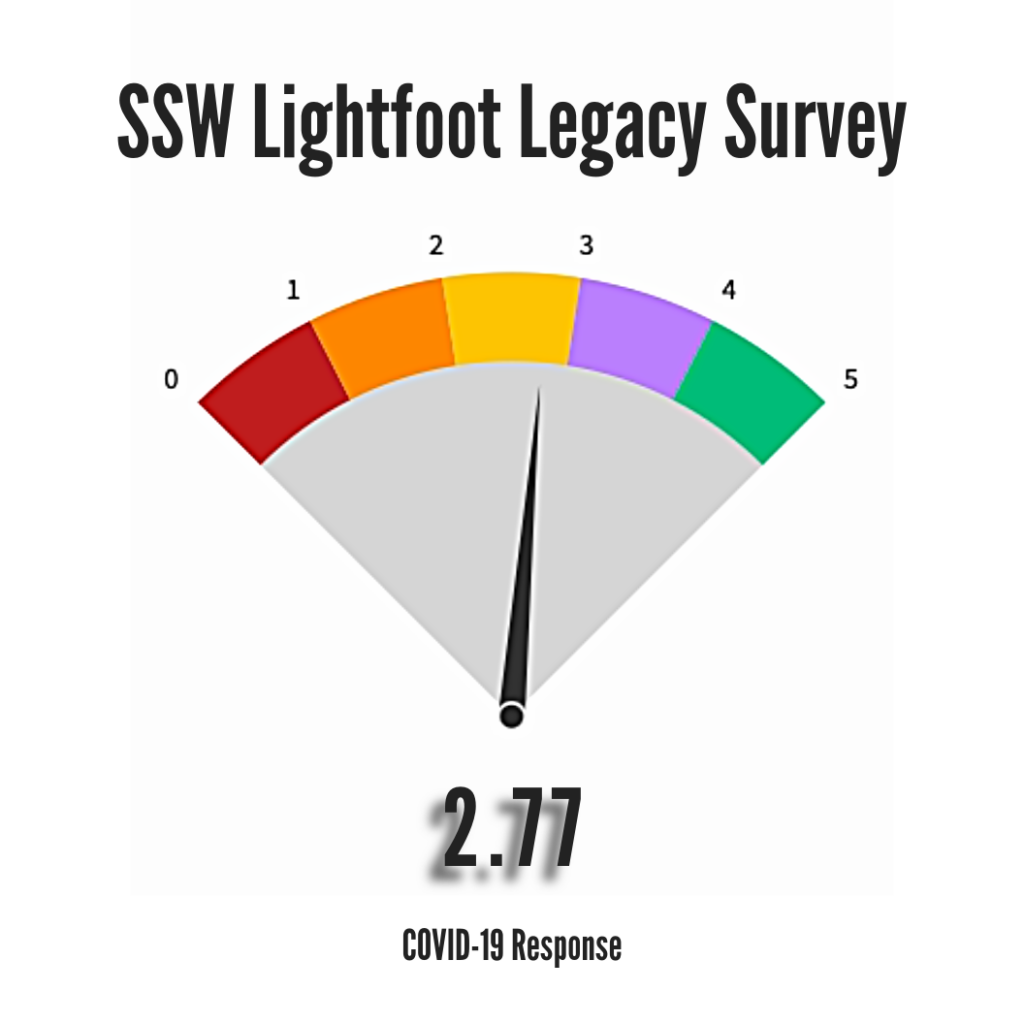

Like Glenn Harrell, Charlene Guss wants better for the South Side, she relayed while driving home to her Douglas neighborhood. A lifelong Chicago native of sixty-eight years, she rated Lightfoot higher than average on all six categories. Reflecting back on the highlights of her tenure, Guss praised Lightfoot’s COVID-19 response. “She did not drag her feet in response to COVID-19.” Speaking from her experience living in Douglas during the pandemic, Guss recalled that “there were facilities in places where people could go for testing [and] vaccinations…and there was also continual outreach about what people could do, what was in their best interest.”

While Lightfoot may have bid adieu on a low note, during her first year, she enjoyed positive approval ratings, according to one poll, for her COVID-19 response in early 2020. Just over half of our survey respondents agreed, giving Lightfoot an average of 2.77 stars out of five.

Lightfoot did not start out as the South Side’s preference in 2019’s municipal election. (Preckwinkle had twenty-three percent of the South Side vote while Lightfoot only had fifteen percent.) However, by the municipal elections in 2023, Lightfoot was overwhelmingly the favorite in many majority-black West and South Side wards.

Guss was an early supporter of Lightfoot since 2019. “I admire [her] initiative to revitalize neglected neighborhoods on the South and West Sides,” she wrote in response to the Weekly survey in May 2023, referring to Invest South West, Lightfoot’s signature three-year plan to pour $750 million in public funds to neglected neighborhoods and corridors. But by 2023’s municipal election, she switched her support to Johnson who she believed would be better at achieving economic equity. Johnson’s directness in prioritizing communities that need support the most rang true to Guss’s values.

“[Johnson] was absolutely right, because there are communities on the West Side that have not gotten…attention since before 1968. And that’s appalling,” she explained. “It is absolutely ridiculous that Logan Square is as beautiful as it is, that West Town is as beautiful as it is…but other neighborhoods on the West [and] South Side have not gotten the same kind of infrastructure attention or support.” Guss will be following closely how Johnson will continue the ethos of Lightfoot’s Invest South West, because like her, “he wants to see more things happening in those areas.”

One respondent from Hyde Park who voted for Lightfoot in both 2019 and 2023, and ultimately chose Paul Vallas in the runoff, also valued Lightfoot’s commitment to neighborhood revitalization. She explained that “there [were] lots of positive news about Invest South West and other neighborhood projects [like new libraries] that seemed flushed away by unhappy teacher/police news.”

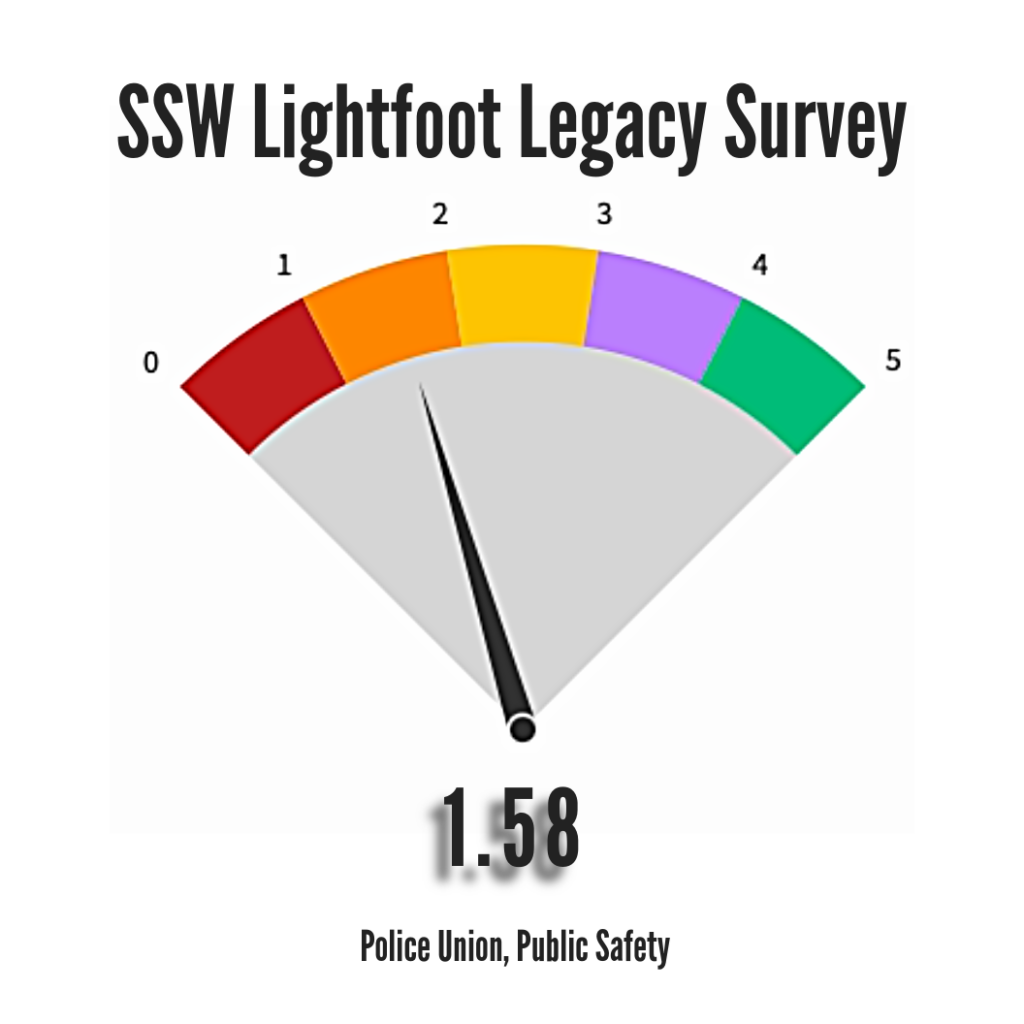

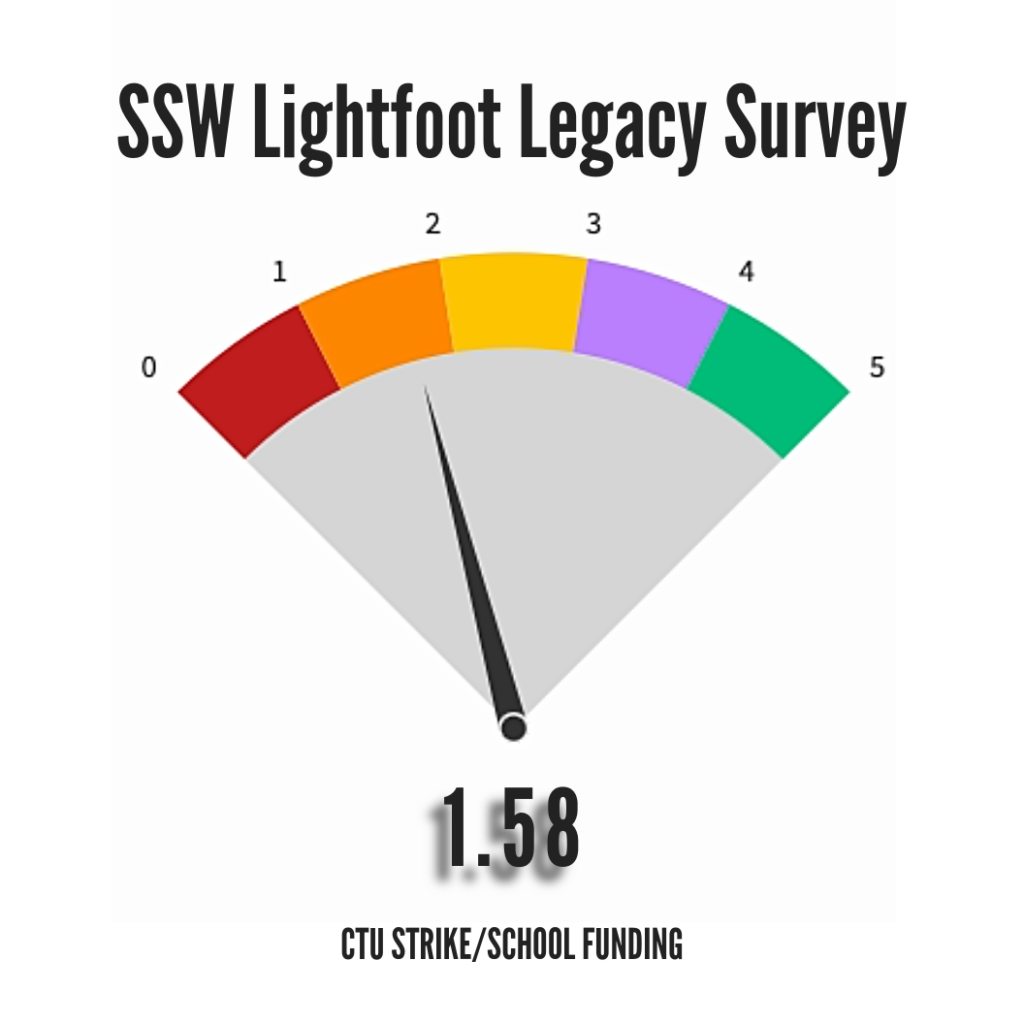

“Unhappy teacher/police news” might be an understatement. According to a survey in February 2023, seventy-five percent of Chicagoans were dissatisfied with public safety, and only thirty-three percent were satisfied with the city’s public education. In the Weekly survey, South Siders ranked Lightfoot’s treatment of both public safety and public education poorly—averaging less than two stars out of five.

Throughout Chicago history, public safety and police misconduct have disproportionately affected South Side residents. According to a 2020 audit, police officers stop Black Chicagoans at overwhelming rates in the South Side and are more likely to use force against them. West and South side residents are also at the highest risk of gun violence, yet suffer the longest wait times for responses to 911 calls in certain neighborhoods such as Woodlawn and South Shore.

Some South Siders’ vote for Johnson was more indicative of their refusal to support Paul Vallas’ perceived racism rather than approval of the policies that make up Johnson’s public safety platform.

“I hate to say it, but Paul Vallas is a racist,” Harrell stated point blank, when explaining his vote for Johnson in May. Guss also contextualized her support for Johnson with her view that Vallas “would be a puppet for the leader of the police union… And under no circumstances do I want to do anything to support the current Fraternal Order of the Police leadership [John Catanzara]. That man is a racist.”

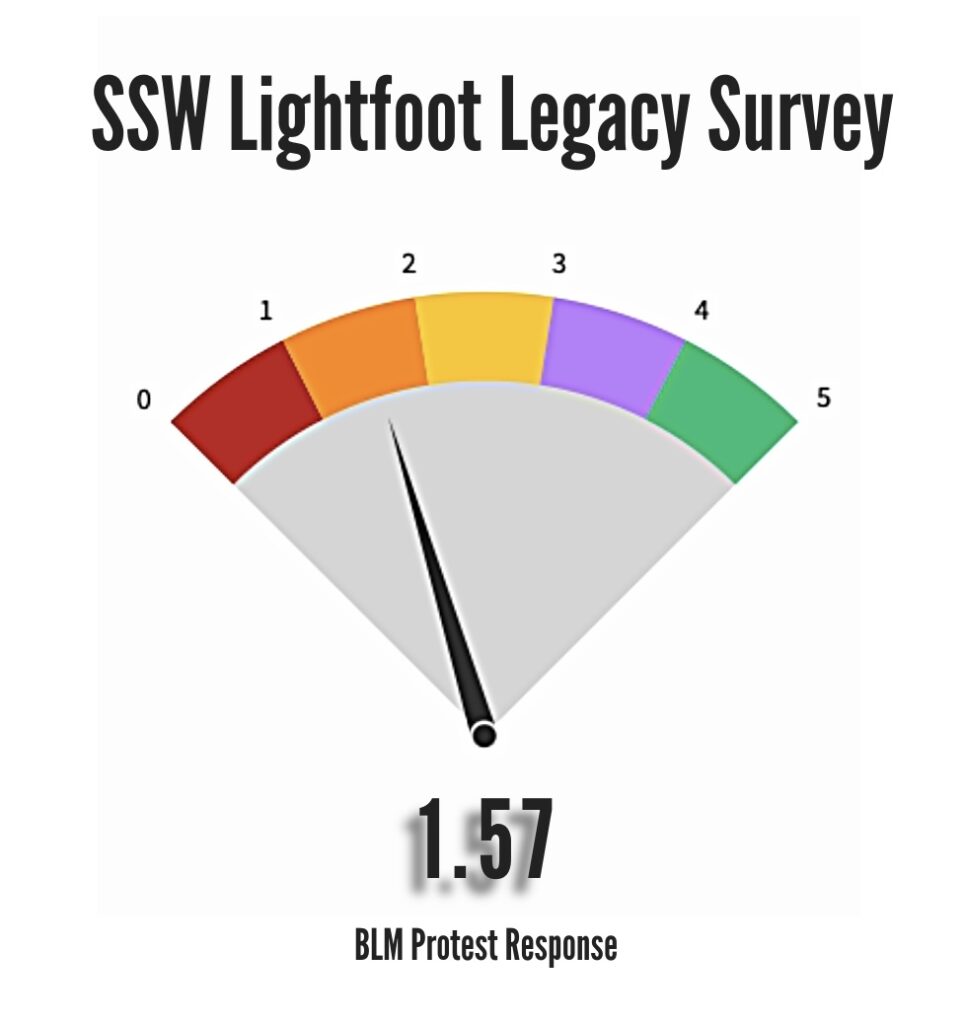

Several South Side respondents stated that their memory of Lightfoot is negatively defined by her policing responses that seemed to disproportionately target Black youth, especially during the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in summer 2020.

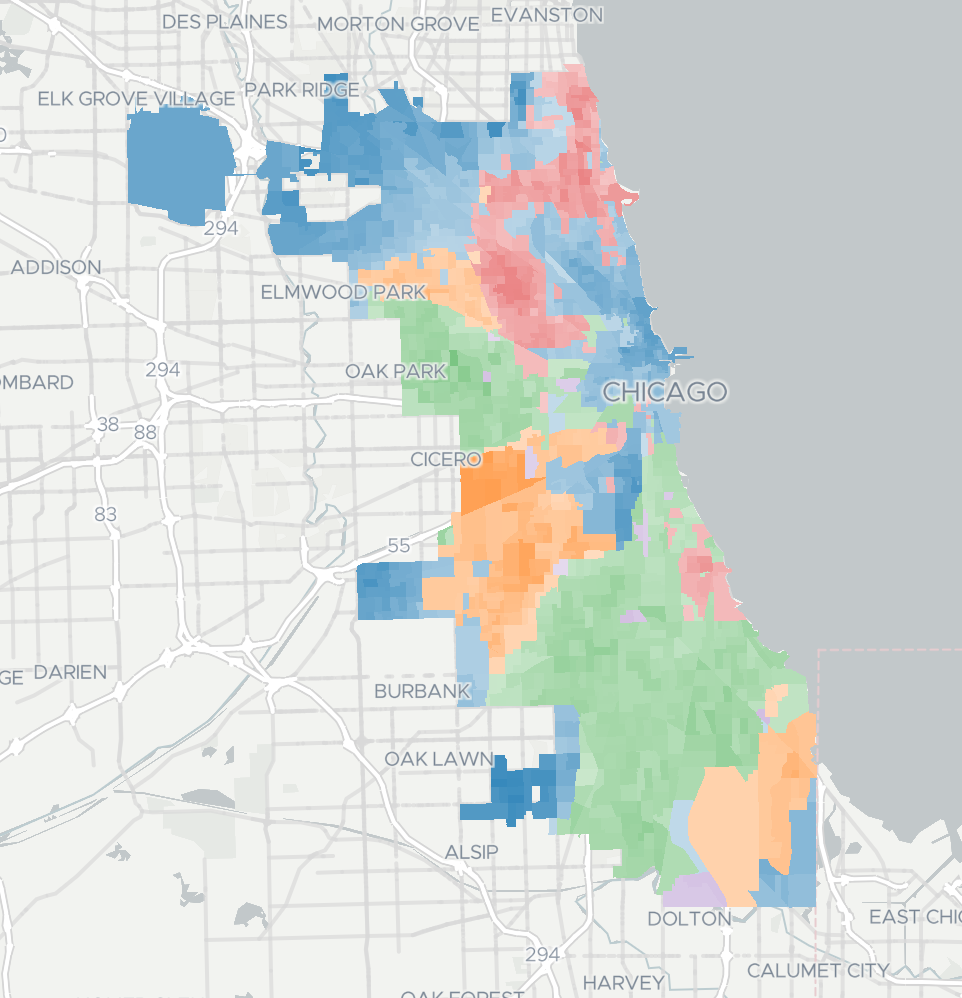

Sativa Volbrecht, twenty-five, moved to Chicago from the suburbs for college in 2016. Since graduation she’s lived in Bronzeville. After qualifying for city residency in 2023, Volbrecht’s first ever vote for Chicago mayor went to Johnson. Like Guss, she was understanding of Lightfoot’s actions in 2020 given the unprecedented context of a global pandemic, but ultimately balked at Lightfoot’s response to the BLM demonstrations.

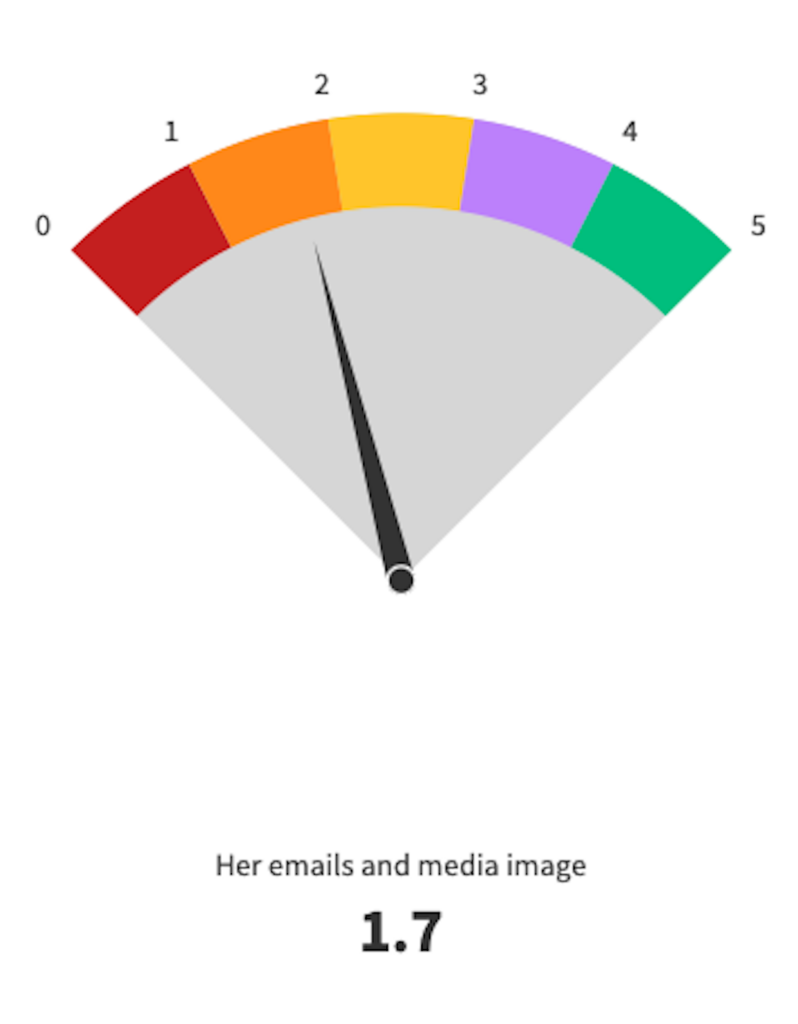

In response to BLM protests in May and June 2020, Lightfoot ordered to raise the bridges connecting downtown with the northside, installed the National Guard to man checkpoints, and increased CPD patrols, for which a watchdog organization found that CPD underreported baton strikes used against crowds. South Side Weekly compiled over fifty testimonials on excessive use of force reported on May 30 alone. In the Weekly survey, South Siders rated Lightfoot’s BLM protest response the lowest out of any of the provided categories at barely over 1.5 stars.

“It, to me, was sending a message…that protesting isn’t welcome, which I don’t think is the right response to protestors,” Volbrecht explained. She prefers a more rounded approach to addressing public safety than Lightfoot’s, which, to her, felt heavy-handed. “I personally felt that the South Side is over policed a lot, and I think that it increased under Lightfoot,” Volbrecht said.

Like Volbrecht, for Anna Schibrowsky, Lightfoot’s decisions during the short but volatile period in June 2020 defined the former Mayor’s legacy, specifically her decision to barricade downtown from the rest of the city. Schibrowsky, forty-four, has lived in Bridgeport for over twenty years and works as a marketing coordinator in commercial real estate. Schibrowsky, who voted for Preckwinkle in 2019, only became more disillusioned with Lightfoot’s leadership by 2020.

“The photos of the bridges raised have become iconic and traumatic,” she said. “The thing I’ll never forget is that Lori had the National Guard barricade off northeast Chinatown from the grocery stores in southwest Chinatown. Volunteers had to skirt blockades of armored vehicles to take fresh produce to elderly Chinese Americans during a pandemic.”

Though Lightfoot requested in June 2020 that Governor JB Pritzker deploy the National Guard to surround the downtown area, she pushed back on aldermanic attempts to call on the National Guard in August 2020 to patrol the city. On the South Side, where a higher proportion of residents experienced violent crime, Alderpersons and residents were split over the appropriate amount of force to apply to the situation.

Schibrowsky understands the complexity and multi-faceted nature of addressing public safety—and resists narratives to oversimplify or stereotype opinions. “There’s no one cohesive opinion on the Southwest Side about the police,” she stated. “Some of them are ready to abolish the police because they see young people being harassed by CPD and their futures being restricted by CPD, charging them with things that we don’t see kids in more affluent areas get charged for. But there’s also gun violence, people are saying, ‘Well where is CPD? There was a shooting and CPD didn’t come for two hours.’ I think where people agree is that CPD is doing things we don’t want.”

Schibrowsky voted for Johnson in both 2023 elections. She says that Lightfoot did not prioritize Chicago Police Department reform and that “under Johnson, I would like to see the consent decree compliance, prioritize[d] and forward[ed] more quickly. I would like to see us start having mental health first responders who are not accompanied by people with guns, I’d like to see the new police district council tak[e] seriously community complaints.”

Environmental racism is another concern for the South and West Side, in which the city’s heavy industry is disproportionately concentrated and in which the city’s highest percentage of Black and Latinx residents live. Inside Climate News deemed these areas “sacrifice zones” which is defined as populated areas with high levels of pollution and environmental hazards where the health and safety of residents is sacrificed for the economic gains and prosperity of others.

Under Lightfoot, an investigation conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in July 2022 accused the city of not listening to Southeast Side residents’ opposition to General Iron. HUD ultimately deemed the handling a violation of Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Lightfoot rejected General Iron’s request for a permit.

Johnson campaigned on a Green New Deal, including a comprehensive study “of this city’s environmental needs, with a focus on identifying the hazards on the South and West sides.” Johnson suffered with asthma as a child and currently lives in Austin, one of the most polluted areas in Chicago. Both Volbrecht and Schibrowsky will be closely following Johnson’s commitment to reinstating the city’s Department of the Environment, which was dissolved under the Emanuel administration. Johnson’s Transition Report sets out to not only reinstate the Department, but to match or exceed funding for the previous Department with a $5 million budget.

In her free time, Schibrowsky volunteers with Southwest Environmental Alliance, a grassroots organization combating environmental racism in the Southwest Side. During a community forum she attended during runoff season between Vallas and Johnson, she recalls that Vallas had made stronger commitments to the Southwest Environmental Alliance. Nonetheless, Johnson’s less pinned down answer made a positive impression on Schibrowsky. “He was like, I’m not going to commit to not issuing any permits [to industrial sites] because some communities might actually want those permits issued and have more jobs in their community. The fact that he was not always telling us just what he knew we wanted to hear, but telling us he would listen to individual communities…That was strongly in his favor for me.”

Schibrowsky said that Southwest Environmental Alliance tried to secure meetings with Lightfoot during her tenure, but that “she kept refusing…she didn’t want to listen.” Though the Alliance has yet to meet with Johnson directly, Schibrowsky said they did convene with his chief of staff in August. “So we’re already seeing someone who’s more willing to make his staff available to listen to the concerns of the community. Hopefully, we’ll see more action in addition to that.”

As of June 2023, Johnson has also stated that he will fight to appeal a ruling allowing a permit to operate a metal shredding and recycling facility, Southside Recycling (formerly General Iron), at 11600 S. Burley Ave.

Shepherding promises off the campaign trail and into the mechanisms of city bureaucracy requires finesse with both the science of rigid processes and the art of collaboration.

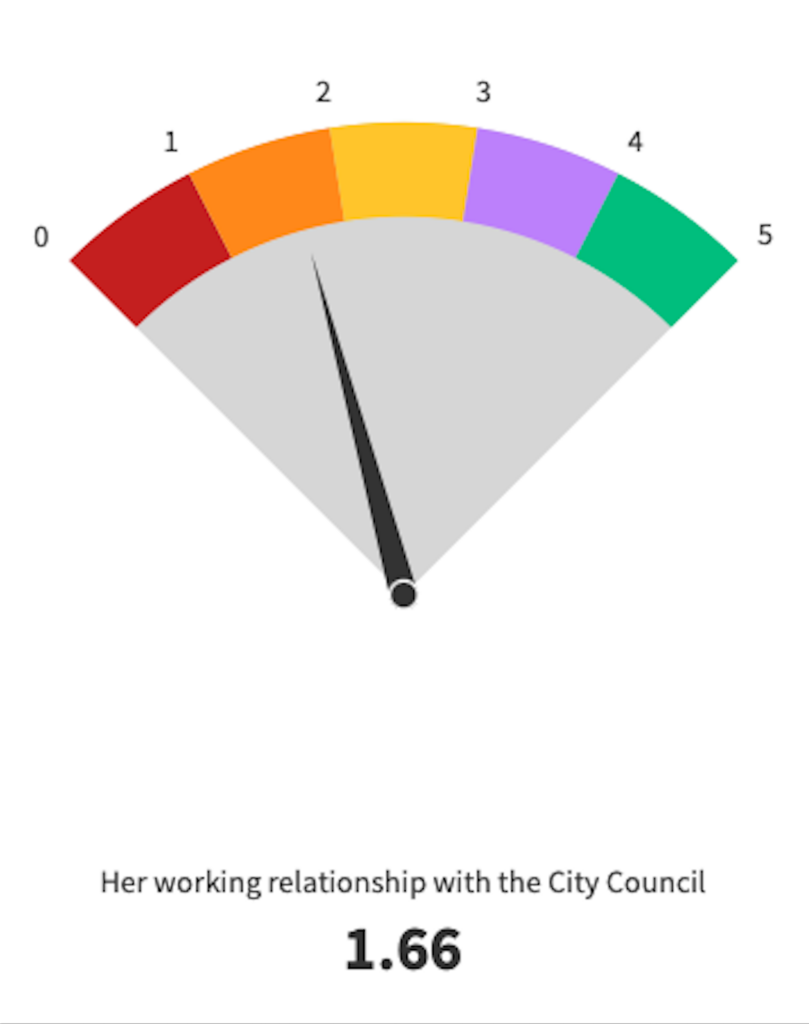

“I strongly feel that what defeated her in not accomplishing more, was her abrasiveness. Lori’s attitude was ‘my way or the highway,’” Harrell said, touching on a common thread between most respondents who lost confidence in the effectiveness of Lightfoot’s strong-headed leadership style to build the political support needed to get things done. Several respondents mentioned her lack of collaboration as a defining weakness. As one respondent to the Weekly survey put it, “she may be the only politician who could alienate the cops and the progressives.”

One of the public quarrels referenced the most by survey respondents was Lightfoot’s fraught relationship with the Chicago Teachers Union. Education is a huge issue for voters, especially for South Siders. As SSW reported, “a large majority of the schools closed [in 2013] were on the South and West sides of the city where the students were majority, if not completely, Black or brown.” The CTU itself is a political force that contributed over $1 million to Johnson’s campaign and represents over 25,000 school-related professionals in Chicago.

Despite her support for Lightfoot’s economic and health policies, Guss was ultimately “disappointed by…her verbal sparring and bickering with [teachers] union leadership.” After Lightfoot’s refusal to recognize the overwhelming CTU vote for a return to remote learning in January 2022, due to the rise in COVID cases, the union walked out. Over the five days of school closure, the #LoriLockout hashtag trended on social media to follow CTU’s teachers “burned” by Lightfoot’s actions to freeze teachers’ pay and lock them out of virtual classrooms. Union Vice President Jackson Potter by January 2023 characterized the union’s relationship with Lightfoot as “with this mayor, something that should become a cakewalk is always a dogfight.”

Johnson’s history as a CTU organizer and CPS teacher, and extensive record of collaboration with CTU solidified Guss’s vote for him in both 2023 elections. “I think his past involvement with the teachers’ union will help us in a peripheral way; it makes the people who are leadership in the teachers’ union feel… that they have an ally, who they can tell what they want.” Allyship between the mayor and CTU is going to be especially important starting in 2024 when CTU will increase their bargaining power in city policy. For the first time, Chicago will have an elected school board, which will start with eleven seats appointed by the mayor and elected ten seats.

Volbrecht also welcomes an amicable mayoral governing style with the teacher’s union. She felt that the framing of Lightfoot’s comments on CTU actions sent the wrong message—that “teachers didn’t care about the kids that they were teaching.” Lightfoot had characterized the CTU strike in 2022 as “an illegal walkout” in which teachers “abandoned their posts and… abandoned kids and their families.”

Volbrecht liked that Johnson “talked about [the CTU protest] in a nuanced way. He’s like ‘okay, you know, the children are important, but people deserve good working conditions and good leaders.’ In general, he tends to take a more nuanced view of things in a way that I really like.”

Harrell has seen nine Chicago mayors come and go in his lifetime and is optimistic while realistic about what Johnson can accomplish. “Everything that I’ve seen from Brandon so far, he has no problem compromising,” Harrell said. In response to a question about Johnson’s potential deviations from campaign promises, he replied “[Johnson’s] willingness to backtrack and take another look at it says to me that you’ve got enough sense to reexamine and hear other opinions.…He doesn’t have tunnel vision.”

Every one of the four respondents we spoke with felt it was too early to make any concrete judgment about Johnson’s administration. Harrell will reserve judgment of Johnson until at least six months into his tenure and on “something that he actually gets off the ground. Not ‘I’m gonna do this, I’m gonna do that.’ I mean, actually accomplish it, put it in motion and then see where it’s at.”

“Let’s give him a couple more months, and then we’ll have a better idea,” Schibrowky said. “He’s started changing people in charge of some of these city departments. Hopefully once the new people get in and get familiarized, we’ll see some changes.”

With so many pieces still needing to be put in place, Volbrecht said it will be a year before she attempts to make a judgment on Johnson’s fitness as mayor. “It seems like a long time, but I feel personally, [for] the government, it isn’t that long—bureaucracy is slow.”

Guss found media criticism of Johnson’s early term at this stage to be premature. “I took exception to some things I read in the Sun-Times in [August] because I think it was…sensationalized.”

“I think it’s important to remember that this is Chicago. Who accomplishes anything in this city as complex as it is in just 100 days?” said Guss. “I know if we had a big snowstorm, we’d have that [cleared] up in less than 100 hours. But in terms of our problems, I don’t know that anyone could finish them. Even if they started, we’d be criticizing them.”

Wendy is the immigration section editor at South Side Weekly and covers interracial solidarity between communities of color.