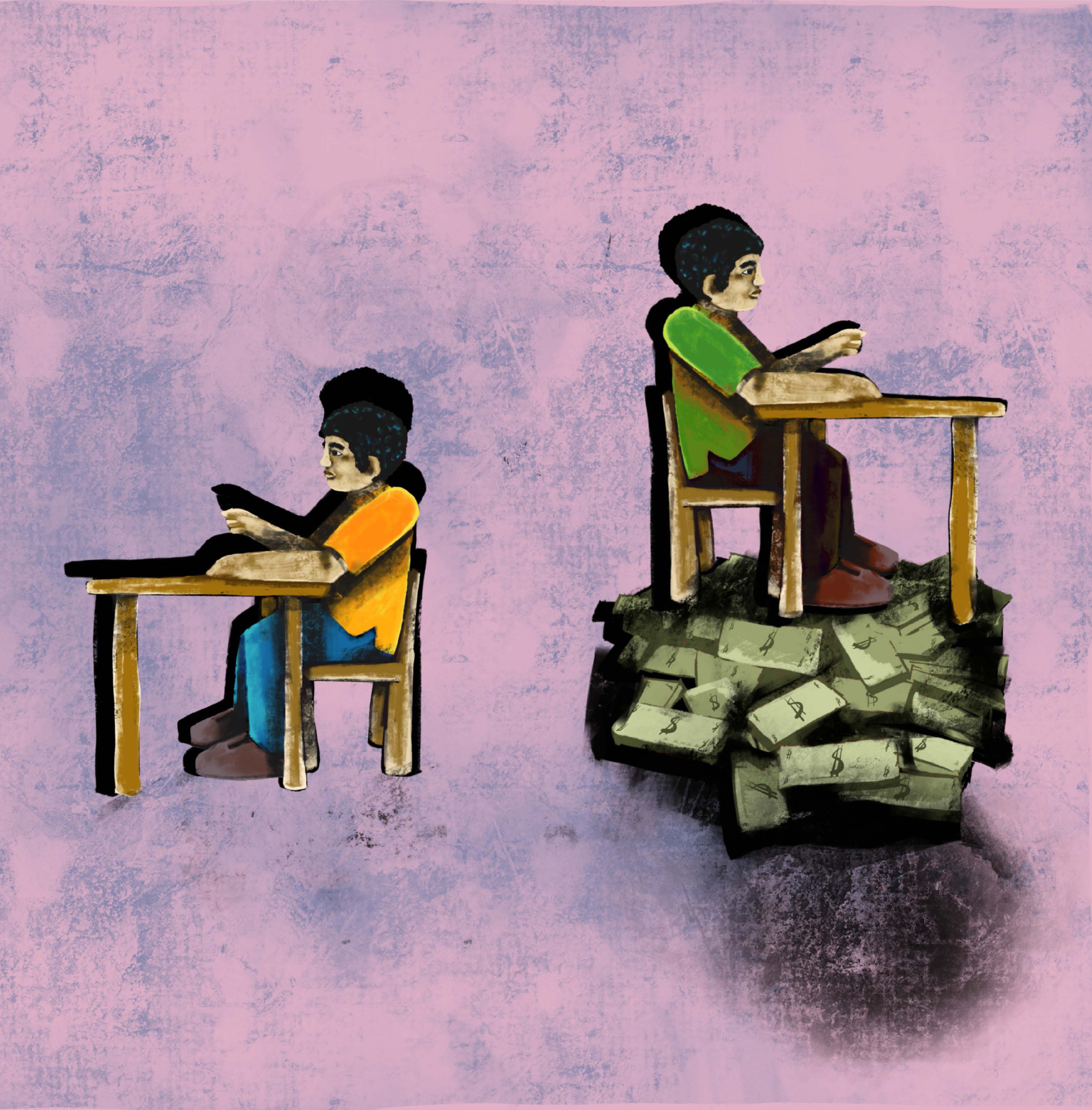

Last August, the Illinois General Assembly passed SB 1947, an education funding bill aimed to make funding more equitable, which also allotted $75 million towards a tax credit scholarship program for low-and middle-income students. Added as a compromise amendment to SB 1947 and called the Invest in Kids Act, the state’s first tax credit scholarship program is, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, one of the largest in the United States. With the new bill, low- and middle-income students can now pursue private educational opportunities—instead of being limited to attending an underperforming public school district in Illinois—through donations from families or corporations to one of Illinois’ nine Scholarship Granting Organizations (SGOs). SGOs then portion out their donated funds to cover all or most of the cost of tuition for low- and middle-income students who apply for these private school scholarships.

On May 22, Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education (RYH), a public education advocacy group, hosted a forum at Kenwood Academy High School on these tax credit scholarships, which one of the panelists described as a “backdoor voucher program,” likening the scholarships to government-funded vouchers for private schools. Like vouchers, tax credit scholarships divert public tax revenue to non-public schools.

Donors to SGOs receive a seventy-five percent tax credit based on their donations. This is different from a deduction because a tax credit reduces the total amount of tax that is paid whereas a deduction reduces the amount that is taxed. The maximum donation an individual donor can make to the program is $1.3 million (with a corresponding maximum tax credit of $1 million). The state has set a maximum of $75 million in the amount of tax credits it will allocate for this program. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) campaigned heavily against the passage of the bill, arguing that it would take away money from an already financially strapped public school system. For the 2017-2018 school year, 670 schools in Illinois were listed as eligible for tuition scholarships. Of the 177 schools listed in Chicago, 114 of them are private Catholic schools. Scholarships may not exceed $12,973, the statewide average public school cost for K-12 students.

Through the tax credit scholarship program, families earning up to almost two times the federal poverty level (about $46,400 for a family of four in 2018) will receive full scholarships, and those families earning more money will receive scholarships that cover three fourths or half of their tuition. To be eligible to apply, a family can earn up to three times the federal poverty level, and after receiving the scholarship, can earn four times the federal poverty level (up to around $100,000 for a family of four) and still receive assistance in the form of a fifty percent tuition scholarship. SGOs must distribute scholarships to applicants who meet the income eligibility guidelines on a first-come first-served basis, though before April 1 they must give priority to students whose families earn less than 185 percent of the federal poverty or who live in areas designated by the state as“focus districts.” (Chicago Public Schools is included as one such focus district.) Students who have received scholarships the previous year or whose siblings have received scholarships are also given priority.

Christopher Lubienski, a panelist at the forum and a professor of education policy at Indiana University Bloomington, explained that even though Illinois’s constitution contains an amendment that prohibits the direct use of public tax dollars for private schools, these tax scholarships provide a way to get around the legal hurdle imposed by the amendment because third-party scholarship organizations receive the money, not individual families or schools.

Cassie Creswell, co-director of RYH affiliate Raise Your Hand Action, noted that voucher and voucher-like programs can also lead to an increased drain of students out of the public school system—a phenomenon that the district is already experiencing. In a student-based budgeting system like that of CPS, that means that there will be less money for the fixed costs of educating the students who stay in the system. She also noted that programs that fund private schools with public dollars tend to increase over time: neighboring states Indiana and Wisconsin have approved large increases in their voucher programs.

Because no clear funding source was identified for the Invest in Kids Act, it is unclear how the state will make up for its losses from decreased tax revenues. Bobby Otter, the budget director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability and a panelist at the forum, guessed that it might come from cuts to human services, healthcare, public safety, or K-12 or higher education departments, despite the fact that Illinois is still reeling from going two years without a budget.

Otter explained that the tax credits are awarded on a first-come, first-served basis by region, with about seventy-five percent of the credits going to Cook County and Northern Illinois counties. Donors in Cook County have received sixty-two percent of their possible tax credits. The other four regions have much lower rates of participation in the program: after Cook County, donors in Northern Illinois counties have claimed twenty-four percent of their possible credits; in Central Illinois, donors have claimed fifteen percent; and in North Central Illinois, donors have only claimed ten percent of their possible tax credits. Despite Cook County receiving most of the donations and credits, to date, only about $41 million (out of a maximum $100 million) have been contributed to Illinois’s SGOs and about $30 million in tax credits have been claimed (out of the maximum of $75 million). This means that about $45 million in tax credits are yet to be claimed.

Watch a recording of this panel conversation, courtesy of CAN TV:

One of the SGOs, Empower Illinois, lists about 250 schools, including a handful of dioceses and a few schools that are pending recognition from ISBE, in Illinois that have received scholarship donations so far. Sixty-six of the schools are listed as being in Chicago.

Otter mentioned that the fact that so many tax credits remain is somewhat surprising because in other states, the donations and tax credits are maxed out “in minutes.” He speculated that the newness of the program could be one reason why the program is not maxed out yet. Another reason could be that taxpayers cannot double dip: if they take the tax credit for the donation in Illinois, they can’t claim the donation on their federal tax return.

Lubienski noted that the research findings on the effects of spending public dollars to send students to private schools in voucher programs have been quite inconsistent until three years ago, and the inconsistency allowed voucher advocates to argue that voucher programs “never showed evidence of harm.” Now, with the scaling up of voucher programs in some states, the sample size became large enough for statistically significant findings. Lubienski reported that five studies using this new data all showed large negative effects on students’ learning—an unusually strong finding for randomized studies. Studies on voucher programs in Washington, Louisiana, Ohio, and Indiana all showed a decline in participating students’ reading and math scores compared to the scores of students who did not participate in the programs. However, over time, the negative effects decreased the longer a child remained in a school. After the latest studies, Lubienski said, voucher advocates changed their story and insisted that “test scores don’t matter…we need to focus on other measures, what they call attainment—high school completion rates or college attendance or completion rates.” However, educational attainment is still correlated with the socioeconomic status of one’s peer group, Lubienski noted.

The justification for voucher programs has been shifting in other ways as well. Lubienski said that at first, advocates for voucher programs and charter schools emphasized that they could save taxpayers money because they could “do more with less,” suggesting that charter schools could save money by hiring non-certified teachers and that Catholic schools could provide a quality education at a lower cost per student. But over time, advocates for these choice programs began to argue that they couldn’t do as well as publicly run schools without equal funding.

Jenni Hofschulte, another panelist and president of Parents for Public Schools–Milwaukee, echoed this, recalling a time when “someone from one of the voucher conglomerates came in asking for more money [saying], ‘It costs a lot of money to educate kids.’ And we were all like, ‘write that down!’”

After accusing Milwaukee Public Schools of being too big to navigate and unable to innovate, Catholic schools created their own level of middle management: Seton Catholic Schools, which appoints principals, moves teachers, and shares a single curriculum.

Lubienski noted that those in favor of school choice also argue that the competition created by having multiple schools vying for students will force schools to do better. However, rather than just investing in instruction, schools competing for students tend to invest significant amounts of money in marketing. In many states, Lubienski said, the money for tax credits has stopped going solely to students who were leaving the public sector for the private sector, and state funds have begun subsidizing private school tuitions for families with students already in the private sector. While Otter said that it was unclear how a similar policy might play out in Illinois, he wondered how many families in Beverly currently sending their children to St. Barnabas, a Catholic school in the neighborhood, will receive scholarships to cover their tuition.

Even though tax credit scholarships are being sold as a way to help students in underperforming schools, the latest research still shows uncertainty in the effectiveness of the program for students despite the benefits it brings to its donors. During the Q&A period, one woman reminded the group that the Invest in Kids Act passed without a public discussion on it in Springfield. Hofschulte closed her remarks by warning Chicagoans to “keep your eyes out and follow the money.”

Katie Gruber is a contributor to the Weekly. She is from Cincinnati but has lived in Hyde Park since 1996. She has volunteered for Raise Your Hand in the past. Her book “I’m Sorry for What I’ve Done”: The Language of Courtroom Apologies was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. She last wrote for the Weekly in May about new research on charter school expansion.