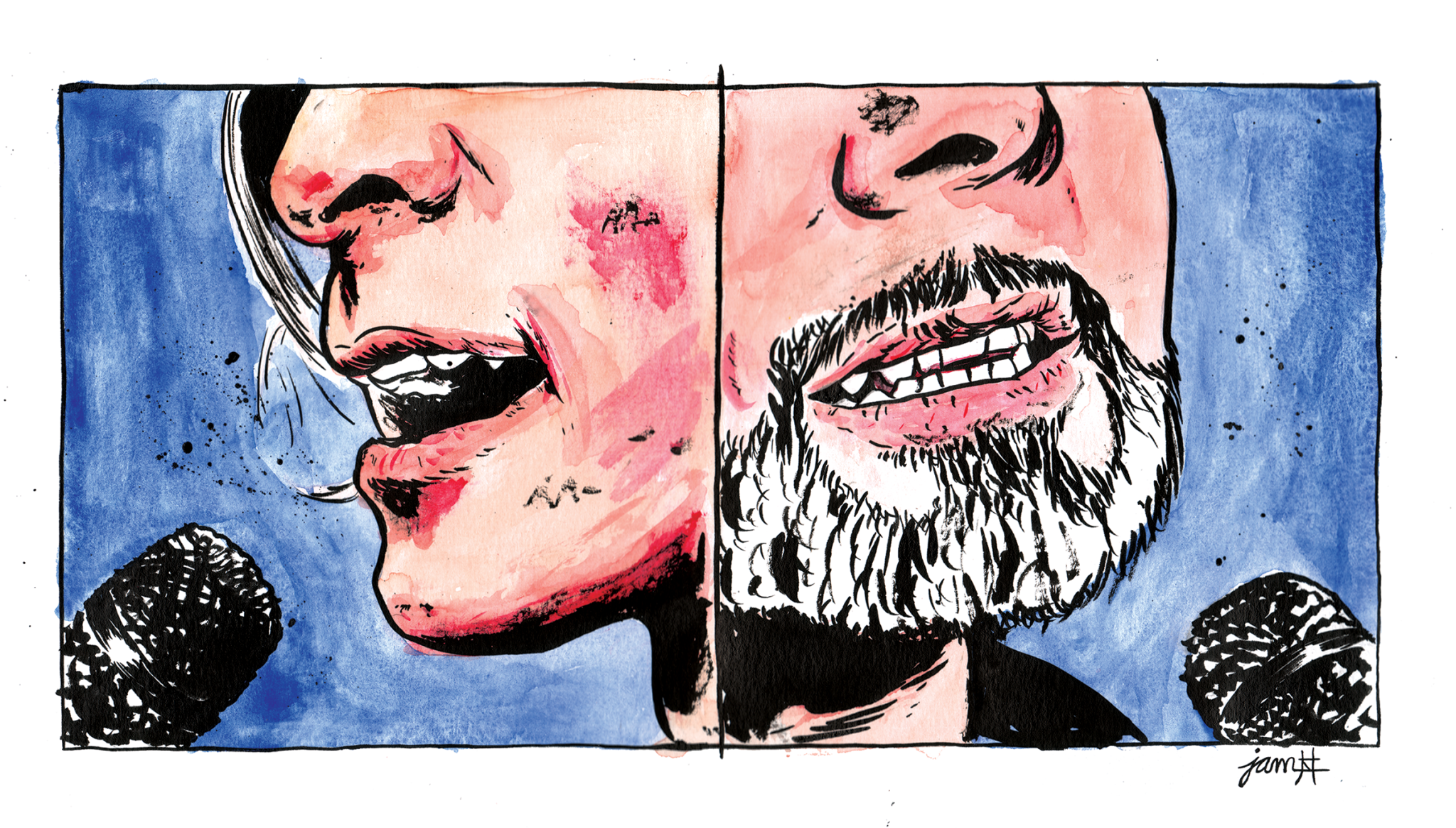

At Catalyst Chicago’s second Classroom Story Slam on April 2, teachers had the opportunity to share their experiences in Chicago’s schools (mainly CPS), focusing on equity (and the lack thereof) in the classroom. In five minutes, each performer painted a picture of their unique experience in education, with a fifty-dollar prize on the line. South Siders Dakota Prosch and Ray Salazar were among the evening’s storytellers. The stories they told are reproduced below, although the names of students have been changed for their privacy. A special thanks to Catalyst Chicago for hosting the event.

Dakota Prosch has been teaching for fifteen years, most recently the fourth through sixth grade at Oglesby Elementary, a neighborhood Montessori school in Auburn Gresham. She told this story as a productive way to process what she called “the most recent and insane thing” in her career.

In all my years I had never seen such a dramatic swing in behavior as this past year.

I met Isaac the spring before fifth grade. He was a charismatic and energetic boy of nine. I was told he had been homeschooled and his mother was overjoyed to have found a public Montessori school on the South Side for her child. The overjoyed part was true. But actually, he had been school jumping for the past few years and just hadn’t landed anywhere for the past six months. Nevertheless, we didn’t have any real selection process or testing criteria and all were welcome. Montessori education begins at three, or ideally birth, with an emphasis on parent education as well, but I had no reservations about letting Isaac join our program since I assumed his educational experience had been child-led, hands-on, and he was independent and fluent in reading and research. But you know what they say when you assume.

That fall, Isaac walked in with his bright smile and was ready to greet the day. Before the next student could shake my hand, she was greeted with, “Dang, what you do to your hair?” We both stood, mouths agape. Speechless. I then realized I had no idea who this child was.

During the first month, our class got accustomed to the peace rug protocols, “I” statements, breathing, doing yoga, holding meetings to solve problems. Isaac wasn’t getting on board. He got agitated when things wouldn’t go his way, insulted students, tried to stab someone at recess, brought a bullet to school. He had no sense of personal risk. His favorite target was a towering sixth grader or the 140-pound fifth-grade girl, named Crystal. I was like, “Of all the people, leave her alone.”

One day Crystal sat him down and said, “This is Montessori. We don’t fight. We use our words to solve problems.” I was impressed and relieved. They would get him on track. But her advice was to no avail. As he rejected the class’s social mores, they rejected him equally as harshly. It was open season and he was the duck.

The class fell apart quickly once the fabric of our class culture was being unraveled and Isaac seemed to hold the yarn. But he had help. Students stopped waiting for their turn with the peace stick, wouldn’t complete their jobs, refused to use “I” statements. The peace rug collected dust. By winter break the Montessori method had become all but impossible to implement. Without trust there was no independent work, without the expectation of safety, students could not concentrate. Once the entertainment became setting Isaac off like a firecracker, the lessons crumbled and burned like a black snake on the Fourth of July.

I tried to understand his behavior, read books on ADHD, ODD, personality disorder, anxiety, and finally settled on reactive attachment disorder, which is so serious that a teacher cannot expect to deal with it on her own. I felt hollowed out.

One day he bolted from the classroom yet again. It took three adults to track him down and take him to the office before he was SASSed. If you are in certain CPS buildings you know this means that someone from the mental institution is coming. This was serious. They said his explosive outbursts were so uncontrollable that he was going to spend at least a week in outpatient care. They said, “Bring him tomorrow.” I went home breathing a sigh of relief. The next morning, in he strolled, the smile from September a distant memory. He told me he wasn’t going anywhere. So it was for another…long…month. I convinced his mother to take him to a doctor.

His in- and out-of-school suspensions were beginning to mount. One day, after his eighth suspension, a doctor called to ask for my assessment of the charming boy he’d met. He had spoken to Isaac, who had said he was fine. He was getting all As. I stuttered. “We don’t give grades in Montessori.” We spoke at length about my frank and pained observations. I knew there was a little boy in there that was hurting and fighting like a caged animal. If only we could unlock the cage and free him. The doctor sounded shocked.

A few days later his mother told me tersely that her son would be starting medication. The very next day, in walked a smiling, if a bit nervous, sweet boy I almost didn’t recognize. He came up to me and gave me a hug. “I am ready to work.” I felt like I was holding the hand of an accident victim learning to walk again. I talked him through his anxiety about learning, but this time he was able to keep it together. He persevered. He listened, he could breathe again.

He was no longer deserving of the reputation of pariah, but sometimes with kids, stigmas stick. I figured it would take time for the class to come around and see the new Isaac. But a curious thing happened. The chaos the class had come to expect was no longer his fault. He was not the fall guy for every fight, not the cause of all the problems.

But they resented him for taking away their circus, their get-out-of-jail-free card. And the more he stood up for what was right, the more they closed up ranks.

On one particularly bad day, Isaac called an impromptu class meeting. Everyone sat down and he announced that the class was being very disrespectful to Ms. Dakota. They were making it hard for me to teach and they all knew better. He thanked me for teaching him and always listening to him and helping to make his life better. He said no one had ever done that for him before. Isaac had me speechless. Yet again.

Ray Salazar has taught in Chicago for twenty years. He almost backed out of the storytelling event because he was nervous, but found himself following the same advice that he gives his students: take risks and step outside your comfort zone. He teaches English and Journalism at John Hancock High School on the Southwest Side and oversees the school newspaper. He also keeps a blog on education and Latino issues called “The White Rhino” (chicagonow.com/white-rhino).

I thought I would live around 26th Street until I died. But when the gangs and gunshots got too close, I decided I had to leave.

A vile bunch lives on the Southwest Side. Latin Kings and Latin Queens, the Two Six—male and female—float around looking for a place to perch, destroy, then disappear. These guys and girls presume themselves on street corners when it gets dark, clutching bottles and passing cigarettes from hand to hand.

“Don’t you know the Lawndales only smoke blunts, muthafucka?” says a young punk to another puffing a cigar as I walk by the Little Village Academy playground. Pride is in these punks’ posture, but fear is in their glance.

It’s 7pm. It’s getting dark. The sun sets and more gangbangers scurry out like rodents. Black hoodies keep their bodies warm, their faces hidden. With nothing else to do, they are inseparable. They shout and sometimes shoot to get attention. Their booming cars roll by, thumping and sparking silver from polished chrome. These rowdy guys and girls wake the working class at night and make the sirens swirl and swirl like the chaos in their heads.

But my social consciousness should make me understand. Chicago, like most big cities, boasts inequality. Immigration isolates a population. Color traps someone. Color sets another free. But I cannot justify the gangs.

In April 2002, just when the weather was starting to get nice, close to midnight on a Friday, a car crashed into a day-labor office on 27th and Lawndale. My wife and I were coming home when we turned the street and saw the fire with flames slapping the sky like giant flags. The crumpled Cadillac crackled as it roasted; the smoke dropped its scent on everyone who stared in fright.

Gangbangers surrounded it. The driver, a twenty-two-year-old Latin King, stood shoeless with bandages wrapped around his head. A woman walked up, grabbed his powerless arm, and pleaded in Spanish, “Cuídense, mijo” (“Take care of yourselves, son”). He almost nodded in response. His eyes moved left and right; he wanted to hold someone’s hand.

The Cadillac’s front passenger lay shirtless on the sidewalk, his stomach rose and fell under the paramedic’s hands. In the streetlight, his face looked black with all the blood that spilled from his temple. His mother, recently arrived from working second shift, screamed into the sky. In her wrinkled work shoes, she spun and yelled without control—her insides must have trembled. She made fists from her frustration, went to hit a car window, then stopped and seemed to think that it might break. In panicked movements, she moved closer to the driver with the bandage on his head. He barely moved to mumble, “I’m sorry, señora.”

The passenger’s father, in his dusty baseball cap and old mechanic’s pants, stared silently at his son bleeding on the cracked concrete. There was nothing he could do.

According to the neighbors, before the crash there were three gunshots, frightening as door slams, a couple blocks away. Then silence. Then two collisions. The old Caddy was rammed by a van, neighbors said. The driver lost control, then crashed into the building. Three of the passengers got out by themselves. The front-seat passenger was unconscious as the car began to burn.

“You have to get him out,” a neighbor shouted in Spanish at the guys. “He’ll burn!” The teens pulled out the sagging body through the window and laid him on the sidewalk. Nothing but the Caddy’s frame was left when the fire was extinguished.

According to the detectives, however, there was only one collision—the Cadillac with the building. “Usually when you get hit, crap falls off the bottom of your car or your lights break or somethin’,” the skeptical detective told a tiny crowd. “There’s no evidence of any impact on the street.”

The neighbors shouted, “No, there were…”

“We heard…”

“Pero eso fue…”

“Before we saw…”

Some of them said they called 911 when they heard the shots. To the detective, those weren’t facts. When he asked the driver what happened, the driver stared blankly and said he lost control. Gangbangers never tell the cops about their rivalries; it’s their own unspoken code.

Four months later, I left 26th Street after living there for twenty-nine years. That last day, I looked at the bundles of books and boxes waiting to be carried away like sleeping children. I threw away old curtains wrinkled as tissue and stared at the overload of memories in a garbage can belonging to the city. The gangbangers won, I thought. I’m the one who has to leave.

But now I know I can still work to address the problems plaguing the Southwest Side even if I do not live in Little Village. I don’t have to live in Little Village to contribute to it. I can’t pay rent there anymore or chase away the gangsters smoking weed. But I can write about those blocks with broken sidewalks in a potent metaphor… or in a simile bolder than any gang graffiti.

If our city leaders invested as much money in our city’s children as they do in graffiti removal, campaigns, and tourism, low-income children could live forever more safely in their neighborhoods. And we could erase the image of an innocent child’s death from our minds.

Because…

When an innocent child dies,

the father, if he’s there, does not cry.

His hands prepare to catch the mother

if she collapses like a curtain.

Then he ambles to a spot.

Sits. Nods.

Implodes.

The mother shrieks.

She swoops to hug a heartbeat

but barely finds her own.

Her hands reach into the sky

to seize the clouds

and shake her child’s soul

from heaven.