On January 11, Tom McMahon stood up to call to order a public meeting at the Pullman National Monument Visitor Center, introducing himself by simultaneously disavowing and affirming the importance of his own place in Pullman’s community: “I’m the president of the Pullman Civic Organization. I’m also a board member of Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives. Tonight, I’m just the moderator, here to ask questions and address concerns raised during the last meeting.”

McMahon was moderating the third community meeting for Pullman Artspace Lofts, a proposed development at the western edge of Pullman, on the corner of 111th Street and Langley Avenue. Artspace, a company headquartered in Minneapolis that teamed up with two local organizations to bring the development project to the neighborhood, has been building affordable housing with gallery and work space for artists across the country since the eighties. Now, after a process spanning half a decade, one of their buildings appears to be coming to Pullman: the current plans for the final complex would include thirty-eight units spread across three buildings. It would also restore a pair of the neighborhood’s historic structures.

But the proposal has divided the neighborhood; resident Mark Cassello referred to the project as “a black eye.” Critics have questioned the wisdom of bringing in renters who might not be fully committed to the neighborhood. They have also pointed out the potential loss of an opportunity to remember some of Pullman’s poorest past residents. And while the meetings were a forum for community members to ask questions and give feedback about the development, some allege that the progress and character of the development were, until recently, shrouded in secrecy; Bob Vroman, who lives across from the current site, said he felt “deceived” by the process. Now, in a surprising change, a concerted community effort may have shifted the original plans for the project from a single structure on Langley to a two-part development at opposite corners of the neighborhood.

Yet the Artspace development is only a small sign of what’s to come in Pullman, a neighborhood readying for change in the wake of its newly acquired National Monument status this past February. In many ways, the debate over the project, with its collision of old and new, reflects the tensions in Pullman as a whole: the neighborhood’s deep historical awareness, the intimate network that exists between its many longtime residents, and the sweeping plans that have been drawn up for the neighborhood’s future.

Over the last couple of years, Pullman has quietly become a hub for many Chicago artists. Matthew Hoffman, who created of the “You Are Beautiful” sign on Lake Shore Drive, produced an installation of the words “Go For It” in Pullman’s Market Square. Local artist Ian Lantz paints murals in the neighborhood’s alleyways and recently opened Pullman Cafe, the only coffee shop in the neighborhood. Conversations about how best to foster this artistic activity have increased along with the presence of the artists themselves. Chris Campagna, who makes his living as an artist, recalls that when he moved to Pullman in 2009, he heard that there were plans to create a workspace for Pullman’s artists.

Campagna, who opposes the Artspace development, claimed that he held one of the first meetings for what would later become PullmanArts, a nonprofit dedicated to growth of the arts in the neighborhood, in his house. Ann Alspaugh, president of PullmanArts, denies that any meeting took place in Campagna’s home. When the group started out, though, it was a committee of the Pullman Civic Organization (PCO), an influential community group.

Alspaugh said the committee’s original plan was to find a workspace for artists from Pullman, but the group soon changed its focus to bringing more artists in from outside the community: “We heard there was a company called Artspace doing artists’ live/work space, and we thought that they could probably do that here.”

After Artspace was contacted by the PCO in 2011, in 2012 it conducted a survey of nearly four hundred artists in the area. Upon finding that there was some demand for affordable artist live/work housing, Artspace agreed to work with the PCO committee, which incorporated as a nonprofit and renamed itself PullmanArts. The two organizations paired up with local developer Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives (CNI), the developer that brought the Pullman Park Walmart and Method Soap Factory to the neighborhood. Eventually the three groups became Pullman Artspace, LLC.

Together, Alspaugh says, members from the three organizations began to pick out a site, eventually settling on the block just south of the corner of 111th Street and Langley Avenue. The site spans three properties, two of which are currently occupied by vacant, almost identical tenement buildings, with an empty lot in the middle.

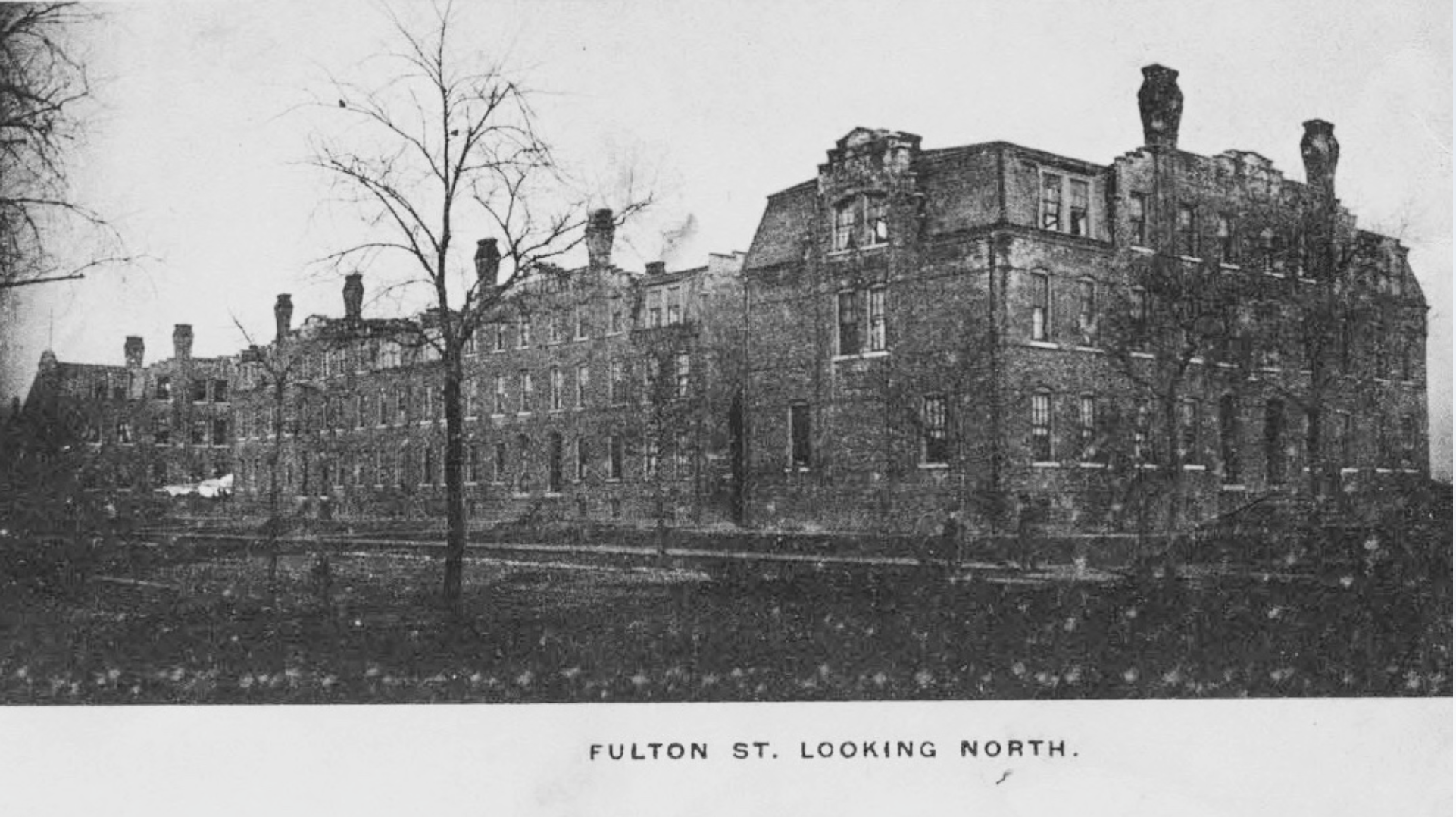

Like the rest of Pullman, the tenements were designed by the architect Solon Spencer Beman in the 1880s, when he was commissioned by railroad car magnate George Pullman to build a model town in an undeveloped area just south of the city of Chicago. But the hulking, three-story tenement buildings (also referred to as block houses) stand in contrast to most of the rest of Pullman’s houses, which tend to be a story shorter and a good deal more compact. Historically, the block houses—originally ten, lettered from A to J—were also where the poorest laborers and their families lived, often in fairly cramped conditions. Block House B, which is now the empty lot, was demolished in the early twentieth century. The remaining ones to the south were also destroyed; a park with a playground and some newer, slightly sleeker two-story apartments now stand in their place.

The disappearance of the block houses is unusual for a neighborhood whose architecture has rarely ever changed, especially since much of Pullman’s permanence is by design. In 1960, Pullman was threatened by plans for industrial expansion that would have demolished the area from 111th to 115th Street; residents responded by founding the PCO. Most of the organization’s lobbying for the preservation of Pullman was on historical grounds, a tactic that proved successful: in 1971, the area of Pullman from 103rd to 115th St. was named a National Historic Landmark by the Department of the Interior, saving the neighborhood from destruction. A host of other historic designations arrived in the coming decades, culminating in President Obama declaring the Historic District a National Monument in February of 2015.

The protections that saved Pullman from demolition also required that it remain, in many respects, frozen in time. According to the Pullman Homeowners’ Guide, residents are currently required by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks to maintain the historical elements of their homes.

Over time, of course, a number of historic structures in Pullman have been damaged or destroyed. The Arcade Building, Pullman’s commercial center that also contained a one-thousand-seat theatre, was destroyed in 1927. Both the iconic clock tower and the Market Square that houses Hoffman’s “Go For It” installation were damaged by fires. The block houses, gradually demolished or vacated, were no exception.

During the initial site selection process, Pullman Artspace found the lots on Langley to be ideal: the site is big enough for an extensive development that could incorporate gallery space along with affordable apartments, and there were willing sellers for each of the three lots. Additionally, the restoration of the block houses could be financed in part by historic preservation tax credits from the City of Chicago.

Artspace selected VOA Associates, an international architecture firm, to design the building for the vacant lot where Block House B once stood. When it was presented to the Pullman public for feedback in early October, the design showed a building with a facade drastically different from the two historic tenements. In response to mixed community feedback, the firm tweaked its plan slightly. The new design pushed the facade back so it flushed with the block houses and modeled it after the homes across the street.

Cassello, an assistant professor of English at Calumet College of St. Joseph, lives a few blocks south of the site. He thinks the choice to construct a new, architecturally distinct building instead of the original tenement would have meant the loss of an opportunity to remember the history of the block houses as the crowded, cramped homes of hundreds of Pullman’s poorest laborers. “Without [the block houses],” Cassello writes in a paper he gave to the Weekly, “a significant dimension of the Pullman story, and hence American history, cannot be told: namely, the story of Pullman’s poorest residents…[The Artspace] project does promise to enhance the two existing Block Houses; however, their new center complex would obliterate the site of Beman’s original building, erase the architectural harmony of the original three building complex, and potentially cause irrevocable damage to the archaeological remains of the original site.” His skepticism is further compounded by the fact that David Doig, the current president of CNI (the developer component of Artspace), has a complicated track record with renovation. In his role as CEO of the Chicago Parks District from 1999 to 2004, Doig oversaw a renovation of Soldier Field that caused it to lose its landmark status and its spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

Cassello would prefer that Artspace attempt to reconstruct the facade of the original building. Barring this, Cassello said that they should move the project to another location. He initially suggested a vacant lot on 113th and Cottage Grove (which Alspaugh says was rejected because it was too small), or some locations in Roseland, the less developed neighborhood immediately west of the Pullman Historic District.

While Cassello’s argument is more historical than legal, Melodie Bahan, Vice President of Communications at Artspace, pointed out that Artspace is simply adhering to the rules that apply to new constructions in Chicago’s historic areas. By the guidelines of the Department of Planning and Development, the City of Chicago requires only that “the design [of the building] respects the general historic and architectural characteristics associated with the property or district in general character, color or texture,” adding that “the intent is to encourage excellence in contemporary design that does not imitate, but rather complements.” A spokesman for the Department of Planning and Development confirmed that these would be the rules that applied to the Artspace project.

The space itself will consist of thirty-eight units, down from early estimates of up to forty-five. The first floor of the middle building will contain a gallery, studio, and community meeting space, but no commercial space, unlike other Artspace projects. Despite the reduction from early estimates, the number of units was another cause for concern among some at the community meeting. “Langley was always bashed as a place you don’t want to live,” said Pullman resident Georgia Vroman. “[It] already has the densest population in Pullman.” Along with her husband Bob, Vroman has lived on the street for the past forty-six years. “Whether this development is going to be thirty-eight instead of forty-eight units means nothing to me,” she added.

Sarah White, the Director of Property Development at Artspace, acknowledged Vroman’s concern, but suggested the number was defensible.

“The density question is not easy to answer,” she said. “The number of units is consistent with what was there historically, actually even a little less.” In response to worries from other residents about parking, a traffic engineer noted that there would be a seventeen-car parking lot in the back, putting the development in compliance with city regulations.

Still, even if thirty-eight units is a feasible number, White’s response on this point seems slightly strange. It’s worth noting what pro-labor Reverend William Carwardine wrote in the 1890s about the buildings: “On Fulton Street [now Langley] are the great tenement blocks, lettered from A to J, three stories, where 300 to 500 persons live under one roof….They are comparatively clean, having air and light; but abundance of water they have not, there being but one faucet for each group of five families.” Because the institutional memory of Pullman is so deep—many residents have lived there for decades, and Campagna likes to boast that his sons will be fifth-generation Pullmanites—it’s likely that part of Langley’s poor reputation is tied to the image of those crowded, largely foreign tenements.

It is hardly improbable that Langley’s reputation should stick in a place like Pullman, where the long tenure and memory of some residents has shown up in other ways for the Artspace project. While seventy-five to eighty percent of the financing for most Artspace developments comes from fifteen-year Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) given to affordable housing projects, White said, the rest is supplied by philanthropic donors and grant-giving foundations. One major financier of the Pullman Artspace project is the Donnelley Foundation, which gave Artspace a grant of $250,000 this past June. Arthur Pearson, the Chicago Program Director of the Foundation, was also Board President of PullmanArts from late 2011 until September 2014; he told the Weekly that he resigned because he had “too much on the work front.” His position at the Donnelley Foundation entails “directing the Foundation’s arts, and conservation and collections programs in the Chicago region.”

David Farren, executive director of the Donnelley Foundation, defended Pearson’s roles in both organizations. “The fact that Mr. Pearson lives in the Pullman community does not constitute a conflict of interest and we took steps to ensure that it would not influence the Foundation’s decision-making process,” he said.

It can be difficult not to find such overlaps in Pullman, though, where pride in the closeness of the community is everywhere. As Georgia Vroman, who serves as treasurer of the PCO but is not involved directly with the Pullman Artspace project, remarked to me, “There’s no such thing as a five-minute walk in Pullman.” Anyone who tries to get somewhere fast will inevitably be stopped at least three or four times by neighbors. At the meeting, one resident noted that when he moved in a couple of years ago, three or four people had knocked on his door within a couple of hours to welcome him to the neighborhood.

Inevitably, this closeness manifests itself in local politics. There is, for example, the case of Tom McMahon, who is both president of the PCO and a board member of CNI. While the PCO is no longer directly involved with the Artspace project (though PullmanArts did present reports at their monthly town hall meeting even after becoming independent), it does wield a good deal of clout in the neighborhood: it was a victory for the Pullman Park Walmart when the PCO supported it in 2010. While the PCO did not respond to request for comment, Doig brushed off any ideas of impropriety, noting that PCO presidents only serve for one year at a time.

There’s also a bit of overlap between PullmanArts and the Beman Committee of the PCO, which makes sure residents keep their homes in tune with Pullman’s historical heritage. According to John Christie, co-chair of the Beman Committee, the committee will vote “to support, not support, or ask for design alterations prior to Landmarks’ decision on the project.” Christie said that while there are two members on the Committee who are also part of PullmanArts, they will recuse themselves from the vote.

Currently, Pullman Artspace has begun its application for approval from the Chicago Department of Planning and Development; the project will also probably have to go through a public hearing from the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. In the meantime, it will begin sending in tax credit applications (Artspace has never been rejected from the LIHTC program before, according to White), with hopes to set up most of its financing by January of 2017. After that, construction would begin, and applications for spots would open soon after. The first group of tenants would move in during March of 2018.

While most or all of the building’s residents will be artists, Artspace’s idea of an “artist” is loose. “We define artist very broadly,” said Melodie Bahan of Artspace. “You’ll find traditional artists, but also performing artists, and designers.” It is also not necessary that an artist make a living off their art; for example, one resident at the meeting who said she was an art teacher would qualify under Artspace’s criteria.

Pullman residents can already observe a local test case in Artspace’s project in East Garfield Park, the Switching Station Artists Lofts. According to Campagna, the lack of development in the area surrounding the building suggests that Artspace exaggerates its ability to bring in commercial development and raise property values. The Switching Station also doesn’t contain a community meeting space. Bahan cited this as a lesson learned: “It makes it a little more difficult for the building to be part of the neighborhood. It is fully leased up, but it’s not as engaged with the community as buildings that were developed after that.” She promised that Switching Station’s shortcomings would not be repeated in the case of the Pullman project. Bahan also pointed out that studies undertaken of several Artspace projects showed property values going up after the construction.

Some hope may still remain for those opposed to the Pullman project in its current incarnation. On January 13, a couple of days after the McMahon-led community meeting, Cassello invited Bahan down to Pullman, where he pitched her an alternate vision for the project. His version would split the project into two parts. The restoration of the two block houses on the Langley site would go on as planned, but the lot between the buildings would remain vacant. And instead of artist housing, the block houses would serve a multitude of purposes: a tenement museum, community workspace for Pullman artists, and a sculpture garden. The residences would then move to some combination of available lots around Cottage Grove and 115th—Cassello is not sure which, though he has suggested a number of available properties—where a higher number of units could still be accommodated.

“The idea is that we’re uniting the northeast and southwest corner of Pullman, surrounding the community with the arts,” says Cassello. “There’s also development that ties into Roseland—you can build along the 115th corridor—which diminishes the stigma that we only develop in a more diverse area.” He added that his plan is “just a synthesis of all the complaints people have had to the project.” I wanted to speak for the people who felt like they were marginalized,” he said.

According to Cassello, Bahan “loved” the plan, but said she had to bring it back to the Artspace development team before agreeing to revamp the entire project. When the Weekly reached out to Bahan, she responded that she was expecting feedback from the development team soon, but did not comment further.

If potential impediments (such as the renewed question of financing) are overcome, and the imagined alternative becomes reality, it would be a dramatic victory for opponents of the existing proposal. Cassello is only cautiously hopeful, but he’s adamant that his idea is best for the neighborhood: “This development could be Pullman’s crown jewel. But if you go through with the other plan it’s going to be a black eye on the neighborhood.”

Of course, change will be coming to Pullman regardless of whether or how the Artspace project is completed. After the neighborhood was declared a National Monument, the National Parks Conservation Association, an independent advocacy group for the National Parks System, and the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects released an idea book called “Positioning Pullman” that outlined and suggested a number of projects for the neighborhood to take full advantage of its newly acquired status.

The book contained suggestions for the restoration of historical structures, like the Hotel Florence—built by George Pullman in honor of his favorite daughter—and Market Square, as well as a reinterpreted construction of the demolished Arcade Building. But there were also recommendations for other sorts of community development in the area, such as boutique hotels or an arts incubator.

Some preliminary work is already set to begin: Lynn McClure, Senior Regional Director at the National Parks Conservation Association, said that money for remediation of the Pullman Company’s factory grounds had been earmarked from last year’s state budget, avoiding this year’s deadlock, and that $7.5 million has been raised for construction of a new visitor’s center, about half the estimated cost. McClure also noted that public transit options to and from Pullman are set to expand as well, saying that the South Shore Line could soon stop at 111th Street.

Still, Artspace, if it succeeds, will be the first new construction in Pullman’s Historic District in fifty years, according to CNI’s Doig. It’s an important test, then, of how a neighborhood that has survived for so long simply on its history can pivot to a new strategy, welcoming the sort of development that will make Pullman more attractive to tourist while also ensuring that the long-standing ties of its residents remains intact.

On this subject, residents at the community meeting, even those skeptical of the Artspace development, were hopeful. “I don’t know what the outcome will be,” said John Cwenkala, who has lived in Pullman for thirty-two years. “I can’t envision what will happen. But the Pullman neighborhood is why they’re here.”

Corrections, February 3 and February 5, 2016: An earlier version of this piece stated that resident Mark Cassello referred to the Pullman Artspace Lofts in a letter to the Sun-Times as “Frankenstein’s monster—economic development run amok.” While Cassello’s January 8 letter did criticize plans for the Artspace development, that phrase referred specifically to the Pullman Park development. The given name of the Vice President of Communications at Artspace was misstated in one reference; she is Melodie Bahan, not Penelope. A reference to what currently occupies a space where some of the former block houses stood misstated the height of the apartments there as three stories high; it is two stories high. This piece has also been revised to reflect that Ann Alspaugh, president of PullmanArts, denies that any meeting for what would later become PullmanArts took place in Chris Campagna’s home.

Terrific, well-balanced article – unlike most we have seen on the subject. As a 25-year Pullmanite and staunch supporter of the Pullman Artspace project, I believe that the most outspoken opponents are also the most willfully ignorant. All residents of the neighborhood had multiple opportunities over the past 6 years to join public discussions and attend planning meetings, yet didn’t. Only now, when the project shows signs of actual fruition, do they poke their heads up out of the sand. I have no objection to the ‘alternate’ ideas presented for artist spaces, and the neighborhood would welcome these kinds of improvements – by all means, ArtSpace all of Roseland and North Pullman as well, if you can! But Mr. Cassello’s, Mr Campagna’s, and the Vromans’ very verbal arguments smack of sour grapes and NIMBY selfishness. Please, PullmanArts, just get this project started already.

This project is not the first construction in Pullman, a small non-descript home for handicapped folks on 111th place and Forestville is about 10 years old and the Medical center at 115th and st. Lawrence happened in 2013 I seem to remember. The artists surveyed in that early survey come from a huge area not just Pullman as the quote implies. Also infrastructure problems abound as does the question of Section 8 housing….the 17 parking spaces conforming to guidelines of federally sponsored housing…privately funded buildings demand one parking spot per unit. The necessary “spot zoning” changes will prove not to be an easy sell here.

Just a small correction. “The remaining (blockhouses) ones to the south were also destroyed; a park with a playground and some newer, slightly sleeker three-story apartments now stand in their place.” There are no newer, slightly sleeker three-story apartments at that location. There is a small block of two-story apartments there.

Confirmed and corrected in the article, thank you.

Why are artists so special? I am a lifelong artist and art teacher, and don’t understand why persons who call themselves ‘artists’ should have dibs on any new apartment complex. I strongly agree, however, that Pullman should have art exhibition space, a performance area, and classrooms to teach fine arts skills. This was, or so I thought, the original intent behind this initiative that I had highly endorsed.

What Pullman really could use is an apartment complex for tradespeople: plumbers, carpenters, electricians, floor sanders, house painters, etc, who are really in short supply in this area of the city. At least once a week, on our Pullman Phone Tree, someone will be seeking practical services such as these. Although this residency request is partly tongue in cheek, my point is: given that the definition of ‘artist’ is loose, why bother to have this designation all? Also, who will sit in judgement of the artists’ worth in being allowed to live here? What are the criteria?

I also agree that Langley parking will be a nightmare. Although the project is legally complying by providing 17 parking spaces, the impact on the people who already live on Langley, already a dense block, has been ignored. I doubt that the average tenament worker had a car when the original complex was built.

This is already probably a done deal, but thanks for letting me add my 2 cents worth.

The questions continue to slow down the start of this boondoggle…why is the Artspace Lofts project afraid of an honest 106 review? Why isn’t the neighborhood kept up to date on changes to this project?

Is John Cwenkala referenced in this article, Cwenk, former IBT employee AND Dad of (black cat) Snowball in EARLY 1970s?