To create his animated film “Consuming Spirits,” Chris Sullivan grasped a needle and prodded at grotesque, vividly colored puppets—which were drawn on paper sandwiched in layers of glass—for fifteen years. Millimeters at a time, twenty-four frames every second, Sullivan brought his characters to life—or, some sort of life. He rolled their paper eyes, bloodshot with colored pencil. He twitched their paper hands, drenched in hangnails, withered with varicose veins; he twirled their paper fingers about cracked cups of paper coffee.

Divided into five parts, the film centers around three characters in northern Appalachia: varicose vein-stippled Earl Gray, whose advice on his gardening radio program drips with meaning; middle-aged, bloodshot-eyed Gentian Violet, who typesets at the newspaper when not caring for her suicidal cancer-ridden mother; and Victor Blue, voiced by Sullivan himself, an ambitionless man who clumsily attempts romance with his coworker Gentian.

“I know: I’m pretty ugly,” Victor coos to Gentian. “And, well, you’re pretty ugly too—that’s why I love you.”

Gradually, these imperfect characters’ lives begin to converge: through corpses in deer-suits declared shamans by local museums, and florets of Destroying Angel mushrooms; through bed-ridden nuns, reclaimed pick-up trucks, and bottles of Allagash beer.

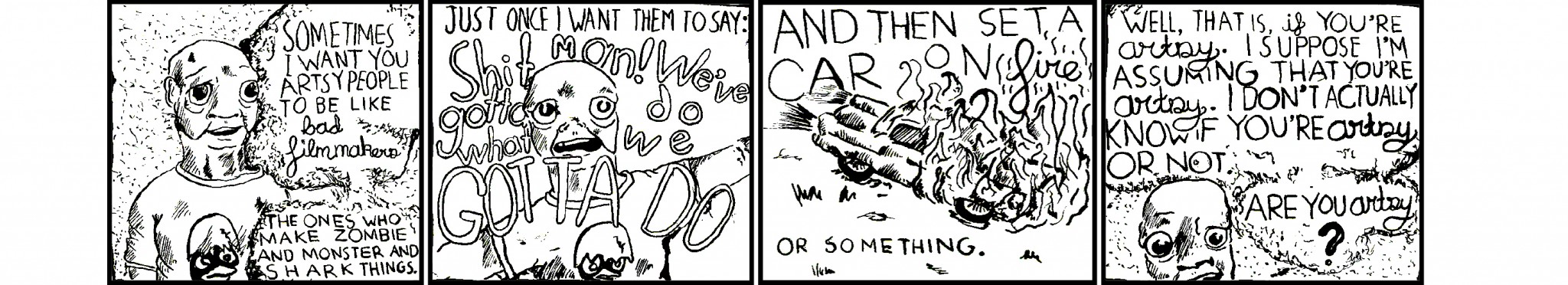

Sullivan, who refers to himself not as an animator but “a filmmaker who animates,” constructed a vast, meticulous world that oozes with detail. On Thursday and Friday evenings, when he visited the University of Chicago to promote his film, the vats of sharply defined minutiae that made up his fictional world seemed to permeate the world of the audience as well.

In a dimmed classroom, members of Fire Escape Films listened to Sullivan while picking at complementary samosas with frail sporks. They rolled crumbs between their thumbs before precariously pouring on fuchsia sauces. Sullivan himself tugged at his shirt, a graphic tee depicting the Italian cartoon chicken Calimero. “E’ un’ingiustizia però!” the shirt claimed: “It is an injustice, though!”

“I like to have people fidget with things,” Sullivan would later tell the students. “I like to have them twitch. No one actually ever just sits still and talks.” Sullivan paused, and tugged again at the sleeve of his shirt. “Well, that is, except when you’re breaking up with someone, I suppose.”

Sullivan showed clips from his current animation project, an exploration of life and relationships in the International Space Station. At one point, he paused the film and pointed to suspended steamy clouds that spewed from characters’ mouths and bodies. Sullivan has been thinking a lot about steam lately.

“These clouds were actually inspired from a road trip I had a long time ago, in the dead of winter,” Sullivan said. “We passed this one cat that was recently run over. Steam was flowing so profusely from its stomach. It was somewhat beautiful—it was awful, of course. But it was also beautiful.”

Much of “Consuming Spirit’s” details are culled from the very details that envelop Sullivan’s own life: the plaque on the shaman’s display in the film’s museum is essentially equivalent to a plaque Sullivan found in the Field Museum. The watercolor-veined Earl Gray’s gardening radio show was heavily influenced by rural-Illinois-produced gardening shows that Sullivan himself would regularly watch.

“One thing I’ve found about these gardening programs, or programs like Car Talk: they don’t actually want to talk about mushrooms. They don’t want to talk about cars. They just want to talk, period. But no one can call up and say, ‘Hello, yes, my heart is breaking.’ They say, ‘Well, I seem to have this fungus on my tree.’ Or they say, ‘Yes, I’ve got this Volkswagen that’s acting up,’ but they’re all metaphors.” Sullivan paused, and looked down at his hands, not notoriously veined. He rubbed at his knuckles. “It’s nice to pretend.”

Later, Sullivan resumed pondering the urge for people to talk. “People like to talk; they will say anything. So much of what we say (is) just little adages from television or movies. It’s a bit disconcerting: ‘Better safe than sorry.’ ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover.’ They’re all the same. They mean nothing. We fill our lives with just stuff. If I go to a party filled with plumbers, the conversation all night would turn to plumbing. And, okay, I’d find that completely trivial and ridiculous. But if I go to a party of filmmakers, we would only talk about film, which is probably just as trivial and ridiculous as plumbing.”

In Sullivan’s film, the characters do distract themselves with talk of fungus, of dying trees. But the substance underneath leaks free from every bushel of shepherd’s purse. Victor calls to the radio show and asks about taming a deer in his backyard, but quickly reveals his urge to run away and live in the wild with the deer.

“It’s just…” Victor wavers on the phone, attempting to stuff books and figurines into a cart. “I have too much stuff—good stuff.”

More than any plot twist, what Sullivan would like you to care about are his characters—to love them for the imperfect, gruesome things that they are.

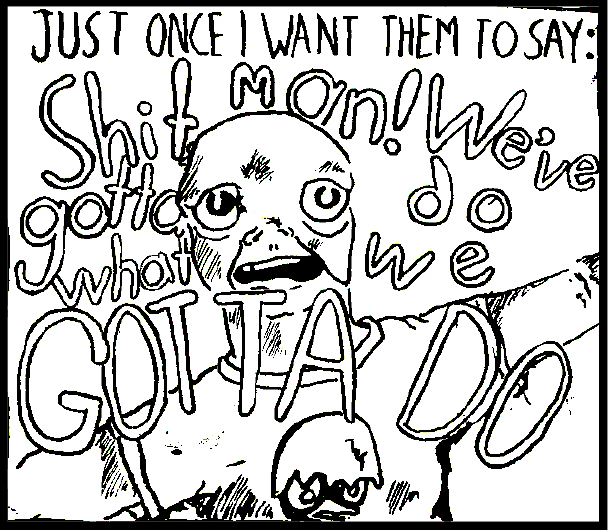

“Sometimes, when I watch bad films, particularly children’s films, the main characters yell to each other, ‘C’mon everyone, we’ve got to go to this planet to save Billy!’”

Sullivan shrugs. “Or not, you know?”

Instead, he admires the approach of John Cassavetes, “who says that life ‘just kind of happens to you.’’’

Much of the life that happened to Victor, Earl Gray, and others did in fact “just kind of happen” to Sullivan himself. “Some things were prophetic: I did get divorced, and I did move into the house that I [raised] my children in.” Sullivan also grew up in a foster family in the presence of alcoholics.

“Yes, I think I’d say this is a historical fiction—”

Sullivan paused, and grinned. “My own actual story, though, is much weirder.”

“But I’m actually not that dark of a person at all. I make dark art,” reassured Sullivan. “It’s those who write the snappy, witty stuff: they’re the spooky ones.”