Friday, April 24th only: “Confessions” at the Chicago Art Department in Pilsen. Seventeen artists submit a written confession and an artistic depiction of said confession. Booklets screen-printed with a giant mouth, lips parted, teeth gritted, will disclose the secrets behind each of the pieces mounted on the walls. This is so that visitors “may see the relationship between the word and visual,” says the invitation.

In the middle of the back wall, on a square canvas as tall as a child are two thick, tar-black parabolas, the left inverted. Artistically it’s an anti-confession, abstract, ambiguous, eschewing standard metaphors like transparency, purification, and spatial depth. The booklet with the written confessions reveals that it doesn’t represent a confession; it is the confession. The artist, Al Prexta, borrowed a squeegee from one of the curators and broke it, then used it to paint the parabolas. “I’m sorry,” he wrote, “But I’m just going to keep it. I will make it up to you somehow.”

That one is pretty straightforward, an admission of wrongdoing cleverly delivered to the injured party. Evidently the injured party doesn’t mind—Tyler Deal, former owner of the now-broken squeegee, tells me it’s one of his favorite pieces. “I love how it occupies the space,” he says as we eye it from across the gallery. It does seem even bigger than its size, quietly dominating one’s gaze even as clumps of people circulate around the room. Quite an apology.

Caroline Lui’s piece is a painting of two white-haired, identical children—the same child painted twice?—pupils near their foreheads, mouths open, smiling with all the detached congeniality of a mannequin. Arching ferns separate them from a curious arrangement of sea-foam balls over an orange backdrop, a pattern that also appears on one child’s shirt. The piece is as eerie and peculiar as the confession: “Every summer for 15 years, a swordfish stared at me while I played pinball. I really miss that swordfish.” Lui explains that the swordfish in question was mounted on the wall of her grandparents’ house where she spent her childhood summers. The painting is titled “Things I Miss in the Dark,” she says.

What exactly is she confessing? Nothing morally wrong or socially frowned-upon or potentially scandalous. Missing the swordfish needn’t be a secret, but it’s the kind of personal nostalgia that is only important because of its emotional significance to Lui. Isolating it in the form of a confession marks its significance, makes the hearer understand that it’s important to the teller.

A joint piece by Jessica Pierotti and Eileen Walsh is comprised simply of the two women’s phones, unlocked and open to all manner of inspection. They both attest to preserving everything, that they haven’t deleted anything since they started the project on April 1st. Despite the seemingly endless possibilities for a voyeur like myself, flipping through their photos and texts is remarkably boring. If there are nudes or incriminating messages, I don’t have the time or patience to sift through all the random selfies and plan-making to find them, which perhaps is the point.

“Oh my God, I recognize someone’s name in here,” a girl looking through the other phone says to me. “Did you find out anything juicy?” I ask. “No,” she says, “it’s just weird.”

In the booklet, Piertotti and Walsh explain their project simply: “Attendants will be free to peruse my private digital environment and will be led to question our definitions of privacy and confession.”

Next I go over to Sara Wright’s piece, a mirror overlaid with thumb-sized fluorescent stickers arranged so that the viewer’s reflection is framed by a heart. The confessions rail against our culture of “playing it cool” and “pretending not to care.” It implicates others, Inquisition-style, I look at myself then lean in to read the stickers: they each say in tiny letters, “Closer to this art than anyone can get to your heart.” I glance up and accidentally make eye contact through the mirror with a blonde girl in a leather jacket. She looks away quickly.

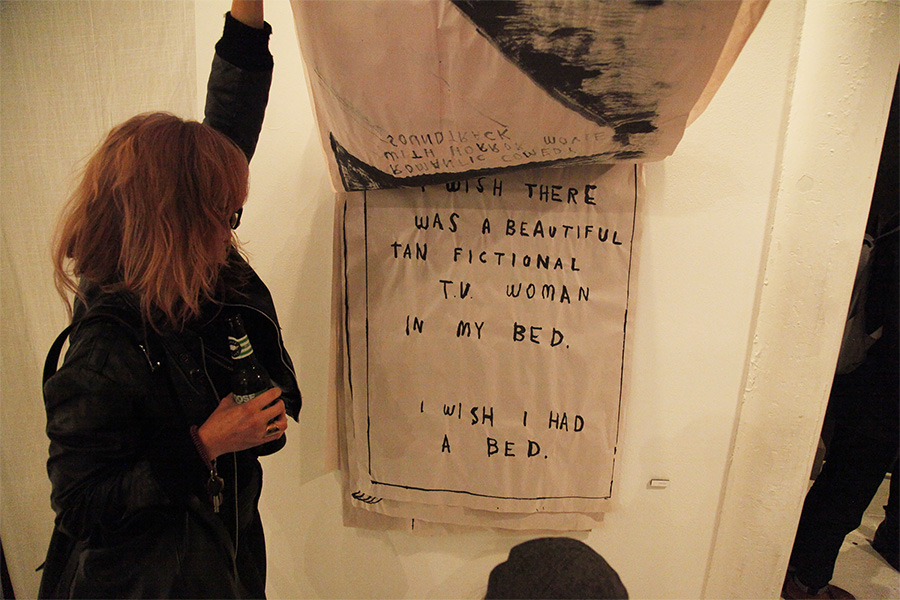

It’s a moment that speaks to one of the themes of the night: reaching out through our isolation and alienation to acknowledge something shared. Curator and former squeegee-owner Tyler Deal tells me that part of the idea for the show was to give people the space to say what they otherwise couldn’t. The whole night feels more like a party than an art show, even by gallery-opening standards—I feel like I’m getting in the way every time I make some prattling group move so I can see the artwork behind them. But beneath all the happy small talk bubbles something a little more anxious, a little more despairing. There’s a bowl in the corner of the gallery and all night people have been dropping confessions written on little squares of paper. “#3 – So True… Yours truly, ‘Successful’ investment banker,” one says. Confession #3 belongs to artist Cooper Foszcz, who fears never finding his passion and the true happiness that’s supposed to accompany it. “I know I’m not the only one who feels this way. But are others faking it?” The piece accompanying the confession is a print of a bird wearing a sign that says “Discontent.”

What makes a confession a confession? The seventeen confessions are as diverse as the art depicting them. Some are tangible sins of envy or stupidity or social impropriety, many are some kind of emotional attestation, of frustration, of weariness. In general, with a few exceptions, these aren’t the type of confessions that lend themselves to gossip, confessions that individuate the person who confesses. They’re slices of our private sameness, worth confessing simply because they usually go unsaid and unacknowledged.

In the bathroom people have been writing confessions all over the mirrors. “I like to sit down when I pee. I’m a guy,” one says. In a different color, with an arrow connecting it: “Dude, me too.”