The January 29 free screening of Stanley Nelson’s 2015 documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution was packed beyond capacity well before the screening’s start time. A crowd of at least ten more milled outside, trying to convince a security guard to let them through the door. Accepting their defeat, the crowd of elders pleaded with the guard to at least allow me in: “She’s young; she’s a student. She doesn’t know about it, but we lived through it. Let her in!” I sat down outside of the door, not sure if I’d be waiting in vain (and rain) for two hours, or if I’d be able to get inside.

About three minutes later, the guard came back and opened the door. “They were using you. If I’d let you in in front of all them, they would’ve come in, too; that’s for certain.”

After sharing laughs, scoffs, and perhaps a tear or two with the audience members in reaction to the insights of police officers, former Black Panther members, and historians, I expected more than half the audience to trickle out before the panel started. Instead, not a soul in the room stirred. The audience wasn’t just here to watch a documentary about the life and death of an influential black organizational movement, but also to learn from it.

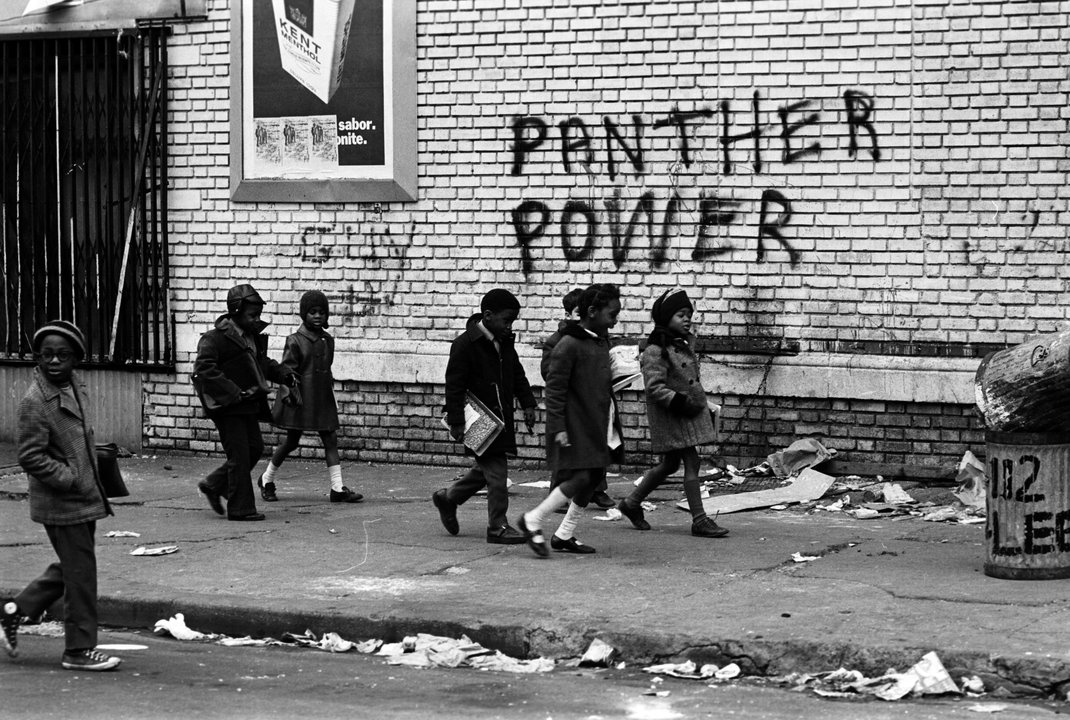

Vanguard acted as an overview of the world of black organization efforts through the lens of this particular historical, influential group, while at the same time reexamining the Black Panthers’s legacy through accounts by police officers, former members, and historians. In this approach, the film itself seems to be aware that it’s dealing with a subject perceived as radical, violent, and little else. The interviews feel warm and lighthearted, making the concept of organizing a body of people into a political force an accessible one to those who find themselves staring the world of activism in the face and feeling shy. The film seems to tell the audience, “We’ve been through this before,” and then encourages its audience to search for answers beyond it.

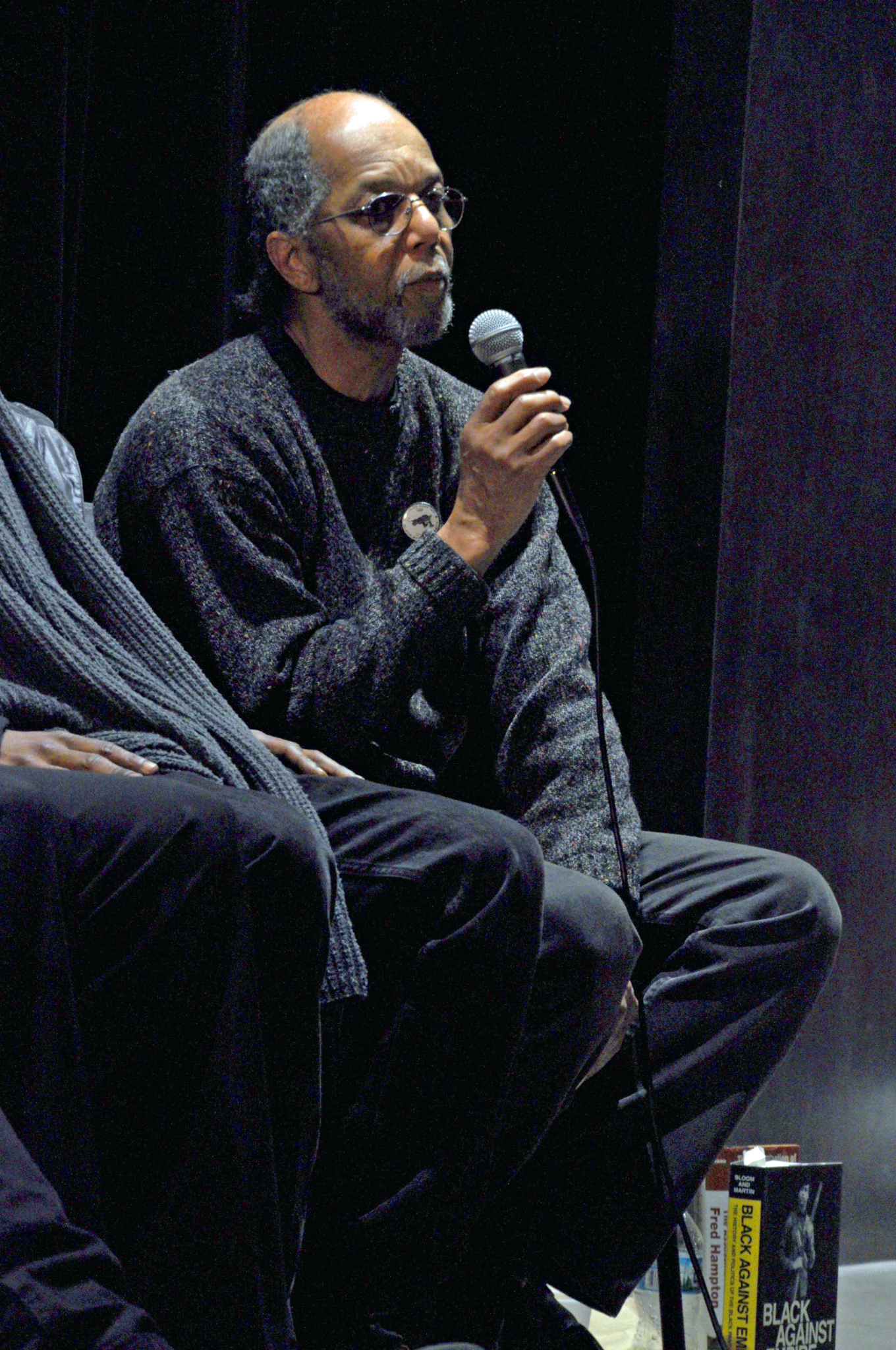

The panel was well prepared to provide those answers. It featured a range of perspectives: Damon Williams, co-founder of the #LetUsBreathe collective and co-chair of Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100); Jane Rhodes, professor of African American Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, author of Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon, and consultant on the film; Bob Madullah, a member of the Prisoners of Conscience Committee, started by Fred Hampton, Jr.; and a former member of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party. The panel was moderated by BYP100 member Imani Jackson, whose discussion points, in addition to the audience’s questions, took the issues raised by the film and contemporized them. The conversation developed into an illuminating dissection of problems that the community faces in the realm of political activism in Chicago today.

In response to a question on the role of women in political and activist organizations, Williams explained how BYP100 works to address the way in which the role of women and young people in these movements have been minimized and forgotten.

“This is one of those [places] where the younger generation has learned from the mistakes of the past,” Rhodes remarked, though she added that part of the infighting was due to a “lack of negotiation” on how power was distributed within the party in general, among women in particular.

Later in the discussion, Veronica Morris Moore, an organizer whose work with Fearless Leading by the Youth was a major part of the movement to bring an Adult Level I Trauma Center to the South Side, joined the panel to speak on coalition building. “It’s also important for us to build community around this issue, and essentially building coalition and community is building power—that’s people power,” she explained. “That’s that bridge…all of these people sat on our coalition to bring both different resources and also different stories to tell.”

Each of the five panelists spoke about the importance of political education and how critical it was to liberating black people from oppressive structures and figures. The former Black Panther member put it eloquently: “I think Harriet Tubman made a good point: she said that she could’ve freed more people if they knew they were slaves,” he said. The film and the panel not only focused on the critical role of political education, but were themselves forms of it.