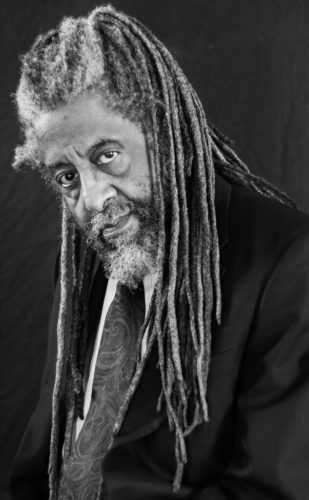

Larry Redmond: My name is Larry Redmond. My nom de plume is Obi. So when people see the exhibit at the gallery people will see a little O-B-I on each of them, which would be me.

Erisa Apantaku: Would you say that you’re a renaissance man? I can elaborate if you’d like me to.

Elaborate.

So you’re a lawyer, general counsel for the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression.

That’s correct.

And you’re staff attorney with First Defense Legal Aid. And in addition, you’ve written and published novels, short stories, plays, photography books, and you’ve raised seven children.

That is correct.

So how do you balance all that?

Yeah…[laughs] Well, really, I’ve been around for a minute. So you can take the time, in a life, to take a few years learning something. For example, when I was a young man, I was a writer, so that’s what I spent my time doing. I thought I was also a poet, but I found out that writing poetry is too hard. So I restrict my writing to prose. But once you learn how to write, you don’t have to learn how to write anymore. You just sort of write when you feel like writing. And so, as a young man I learned how to write, and after that, I learned other things. I learned photography; I went to law school. And each of those takes a chunk out of your life, but once it’s done, it’s done. And so you can move to the next thing.

Listen to portions of this interview on the January 16 episode of SSW Radio, the Weekly’s radio hour on WHPK:

So you’re showing work at the Uri-Eichen Gallery in Pilsen. The event is called Resistance Reception as part of the Do Not Resist? 100 Years of Chicago Police Violence Project by the For the People Artists Collective. What was the process of being part of this multi-artist, multi-neighborhood, multi-event collaboration?

Well, my participation was merely that I submitted some works. They sent out a call for works, for the exhibit that they were planning. And I submitted some works. And they liked them. And I had a question for them—how many pieces can I submit? And they seemed to like the pieces a lot, and they said we’d like for you to put just your works in a gallery by itself. And so I said, cool, I’ll put together a dozen pieces and we can go with that.

The exhibit is multi-locational. Uri-Eichen is merely one location. On the twelfth of January there will be an opening for some other pieces at the Hairpin Gallery up on the North Side, on Milwaukee Avenue, so I’m not sure of all the locations. But it will be multiple flora and multiple artists, it’s just that my particular piece at the Uri-Eichen will be opening on the nineteenth.

And describe the pieces—are they new, old? A mixture of new and old?

They are photographic collages. Actually I photograph a lot of different things, but when it comes to activism, I like photographing rallies. And so, I go to rallies and I photograph the people in the rally. I photograph the cops at the rally. I photograph the signs. I photograph just whatever is happening at the rally. And then I’ll come home—some of the pieces, a lot of the pieces, will stand on their own. But sometimes I like putting them together into a collage, so I’ll take a couple of pieces and lace them together, and then I’ll superimpose other pieces on top of them and make the top pieces transparent, so you can see through those pieces to the piece that is behind it. And that effect is collage-like. I have work here I can show you, it won’t be helpful for radio, but you’ll get an idea of what it looks like. [laughs]

Yeah in fact I’ll get up and take a look at it and if you want to verbally describe what I’m looking at here…

Okay, this is a rally that took place on North Michigan Avenue. This is Tribune Tower back here. And this is one of the pieces—this particular print didn’t make the cut because the color is off a little. You see here how blue that is—it should be grey.

And the Tribune building is…a little bluish, and in front of that, is that the back image? Like you mentioned it’s a collage—so what are we seeing?

This is a collection of some of the people that were at the rally raising their fist. This is another shot of different individuals at the same rally, raising their fist. This is an individual here—I caught this shot of him from the side—and captured that. This line is just the police officers as they were watching us. And this is the commander that was in charge. And if you notice, I’ve got him backwards, because my view is that he is a backwards person, because of, you know—I won’t get into that. But anyway, you can see the Tribune Tower behind these people. You can see things behind the individuals because I’ve made them transparent in the first pieces. But composition—I tried to be cognizant of composition as well. I don’t know if you know about the thirds concept in composition, but the police officers are along a line that is one-third from the bottom of the picture, and this column runs right down this officer and that forms a column that is one-third into the side of the composition. This piece here covers one third of the other side of the composition. These individuals’ heads are along the top third. And so it is composed, it’s not just stuff randomly thrown in. But overall, I like to think it’s a composition that is complete and it’s compositionally satisfying.

Definitely. This reminds me of your other work which also showed at Uri-Eichen, right? That was part of ghosts of slavery in corporate Chicago.

You know about that one? [laughs] Yeah, in fact, it’s the same technique. It’s just it’s a different subject matter. That exhibit was how corporations over time benefited from slavery. And that had some corporate giants in the city and superimposed on those images were images of me in the nude, because I represented a slave. And slaves were nude when they were bought. So I wanted to show how slavery enhanced the corporate world in this country. In fact, just a little tidbit—Wall Street today is what it is because it financed slavery in the south. So, that’s a tidbit of the history.

From what I’ve read about that exhibition, that work was partly informed by a legal case, right?

Yes but I don’t remember all the details of that case…

From what I’ve read I believe an individual brought to the city of Chicago…..I should’ve written this down in my notes but I didn’t…they created an ordinance that corporations…

Dorothy Tillman. Yeah, that ordinance passed. In Chicago. Meaning that—if I recall correctly—that corporations were required to disclose in some way how they benefited over time from slavery. And this is from memory so this information may just be wrong…the lawsuit later on was brought because the city had not been enforcing that ordinance. And so the lawsuit was an attempt to get the city to enforce that ordinance. But the lawsuit failed because the individuals bringing the lawsuit didn’t have standing to do it. Only the city can do that. So if I recall correctly it got dismissed.

When your piece was exhibited at Uri-Eichen, that exhibit was influenced by aspects of that case, correct?

It is correct. Some of the corporations that I took pictures of and superimposed myself onto were… parties to that lawsuit.

So to me, that’s an example of how your work as a lawyer has influenced your photography work. And I’m wondering if the reverse is true. Do you feel like in your law practice you’ve brought aspects of your creative work, be it photography or writing, into your law practice?

Some. But, not an awful lot because I think that my being a writer of fiction helps me when I draft motions and complaints and that kind of thing, because I can be a little more colorful I suppose. But that’s about the extent of it. In terms of material, the lawsuits that come in are the lawsuits that come in. But my legal work to some extent has shown its way into some of the fiction I write…I can talk about that a bit, but that’s a slightly different story.

The event on the nineteenth at the Uri-Eichen Gallery also includes a conversation between you and Frank Chapman. Can you tell us what attendees can look forward to from that discussion?

I’m not sure it’s going to be much of a discussion. It’s going to be more of a presentation. I’m going to give a little bit of background on how the police department in the city of Chicago came to be. And very early on, there was a city marshal, when Chicago was first being formed. And that person was actually elected by the people of the city of Chicago. It was not until the city marshal began to exercise his authority in a way that the merchant class did not like…the merchant class then went down to Springfield and had the state government pass a law requiring that the city of Chicago have a police board that was in fact appointed. The laws have changed over time, but the bottom line is we’re still saddled with the police board today that is appointed by the mayor. That’s the history. Now, Frank will come in and then explain a little bit about what we are doing today in order to try to get back to a position where we have an elected body controlling the police department as we had at the very beginning. So it’s not really going to be a conversation so much as a presentation on the history of policing and what we’re doing today. And what we’re doing today is reflected in the images themselves. A lot of these images come from the rallies and demonstrations that the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression have conducted in order to get community control of the police.

Thank you very much. As someone who photographs these rallies and protests and acts of resistance, can you give insight to other people who strive to document in different ways, be they written reporters or photographers or radio people?

You just have to be there. And the truth of the matter is independent media are doing a good job now documenting the changes that are happening in this country. In fact, a number of them in DC were arrested when your current president was inaugurated. And they faced federal charges. Some of them were journalists who just got swept up in the moment. Because the police were overreacting and just gathered up everybody. Some of these individuals were journalists. Independent journalists, photographers, and writers, and so the independent media is out there. They are doing what needs to be done to apprise the people of what’s happening in this country. And so my only advice would be, you know, keep doing what you’re doing. Keep doing what you’re doing.

Do Not Resist? 100 Years of Chicago Police Violence. Uri-Eichen Gallery, 2101 S. Halsted St. Friday, January 19, 6pm–9pm. Exhibit open through Friday, February 2 by appointment only. (312) 852-7717. uri-eichen.com

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly