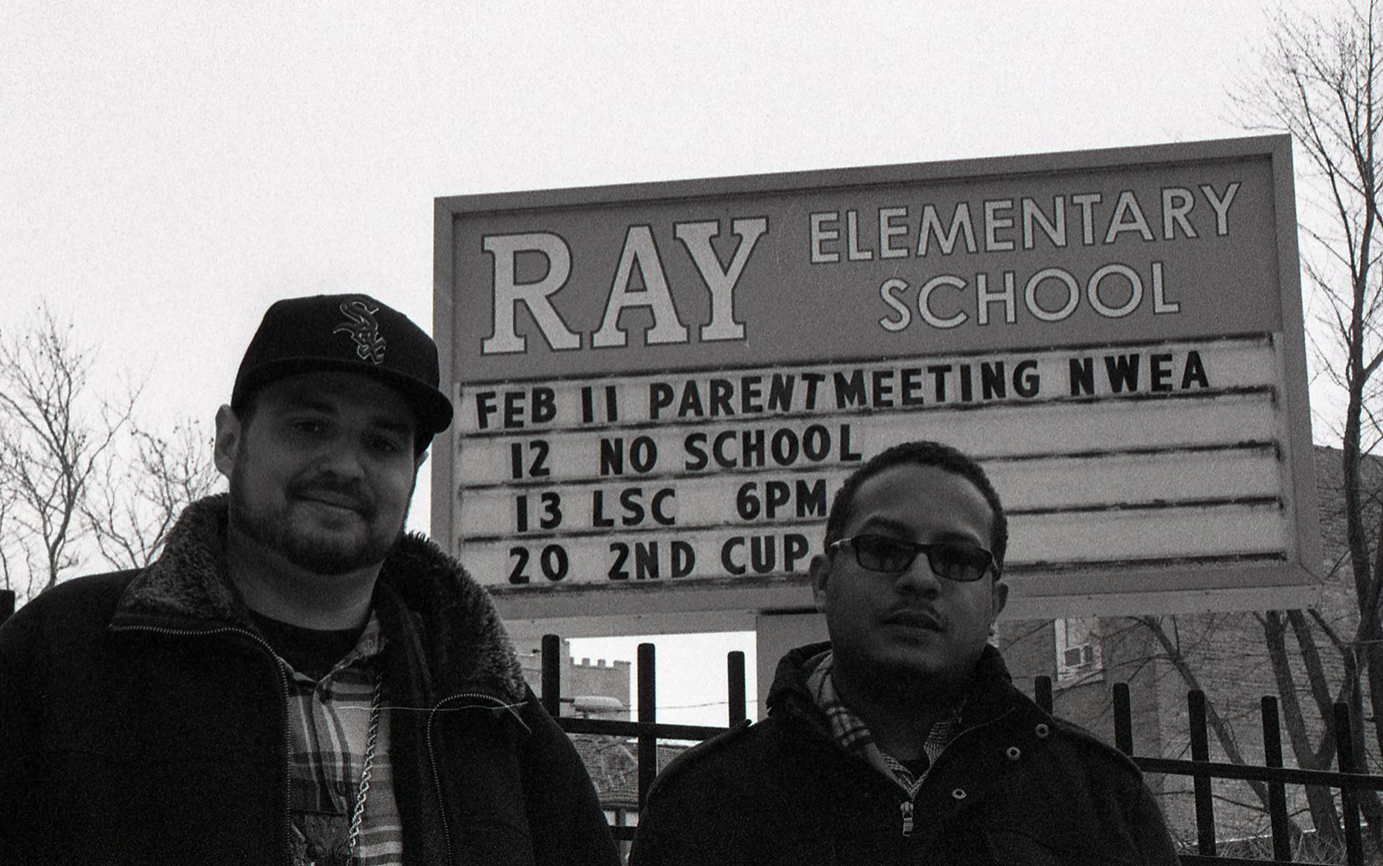

Simeon Viltz and Mulatto Patriot are alumni of Ray Elementary. Together, they’re also hip-hop duo Ray Elementary. The pair just released its eponymous debut, a thirteen-track album dedicated to the Hyde Park elementary school. Viltz has been in the hip-hop game for a long time—a rapper, producer, and instrumentalist, he is half of respected Chicago duo The Primeridian, and has collaborated with L.A. collective The Pharcyde and East Coast production-king Pete Rock. Producer Mulatto Patriot, who graduated five years after Viltz, has worked with the likes of Del the Funky Homosapien and Oakland’s Hieroglyphics crew. Featuring fellow Ray alum Psalm One, Englewood’s Pugs Atomz and Imani from The Pharcyde, Ray Elementary marries old-school samples with live instrumentation. This weekend, we sat down with Viltz and Patriot at Medici to discuss the inspiration for the album, mentoring Chi-town talents like Vic Mensa and Chance the Rapper, and the golden years of Hyde Park hip-hop.

How did the Ray Elementary project get started?

Mulatto Patriot: I was just chilling with my cousin H-Bom, [Horace Hall, a former DJ teaches education policy at DePaul] in Horace’s basement, with, you know, a nice little whisky, and he passed me this Blackbyrds record. He’s like, “Yo, I think it’d be really cool if you make some beats out of it.” So I’m getting all these Blackbyrds samples and chopping them up and I just needed a wonderful soul MC with positive messages to get on it.

Simeon Viltz: I started coming through MP’s house—his lab, I should say—and it was one of those things where I realized he was official. He wasn’t just a beat maker; he wasn’t just an engineer. He was a producer.

I remember vividly the day he played the beat from “Mysterious Vibes.” I used to love that sample. I remember Curious George rocked it. I remember the rapper Paris rocked it. So when he played it, it just brought back all this nostalgia and I looked at him and I was like, “Are you kidding me? You want me to get on this? Of course I will!” I think I probably started doing a dance—I probably started steppin’ or something like that, I was just that excited. That mode, that time period, that was when guys were rapping. They weren’t hiding behind the music, you know.

I started envisioning the record even before I was writing it. We just started piecing it out one by one and the momentum built from there, and then the instrumentation was added after the majority of the album was recorded lyrically, which was cool because the musicians would hear how I was rapping on it and would kind of match the pocket.

Why did you name yourselves Ray Elementary? How did the culture of the school and the neighborhood influence the album?

SV: I always tease MP because I’m the elder—I went there like ten years before MP did. It’s not often that I run into people in the music world that went to the same elementary school I went to. Especially Ray, because Ray’s kind of different. It’s very diverse. It has a history of being a high-achieving school, but it’s also a public school. So I know that MP and I already had a lot in common from that alone. And so I was like, “Why not? Let’s just go with it, let’s name it Ray Elementary.” There are a few direct references in the album that speak on Hyde Park, but it was more of just the vibe. Sonically, Chicago is rooted in steppers’ sets and parties at skating rinks and barbeques. Musically, the “Ray Elementary” album fits in with those environments. The soundscape was also very nostalgic—a lot of samples that had been done before.

What was it like growing up in Hyde Park during the time you were at Ray Elementary?

SV: Growing up in Hyde Park was very unique, very interesting. My favorite time period was in ‘88 or ‘89. It was just so cool to me, because people would be on 53rd Street like it was Times Square. It wascool. If you were young you would walk on 53rd and that was the social spot. It wasn’t all crazy with the police like it is now. It was a lot more peaceful. They used to have these things called YVI games at Kenwood, for Youth Vision Integrity. Think of any movie where they get a bunch of people for a basketball game and everybody’s rockin’ it with their hip-hop out. It was so cool because house music was still the thing in Chicago but it was cutting edge, it was just new and fresh.

MP: I’m mixed myself. My dad’s Jewish, mom’s black. And growing up in Hyde Park was very cool because it is very multicultural. For lack of a better term, it’s not as segregated here. I always felt that I could walk down the street and just say, “What’s up?” and there’s no, like, ulterior motives behind saying hello. It’s not like that every place in the city. I think Hyde Park is special for that, and I think a lot of it has to do with bonding on art and culture. There is something about the people here that is just very worldly, more so than in a lot of places. This was a very diverse neighborhood and I was very thankful for growing up in it. Especially after I moved to the suburbs with my family—that was a big culture shock.

SV: At Ray, I remember in seventh or eighth grade being at a buddy of mine’s, Jeff Hammock, whose house was literally a few blocks from where we are now. It was a huge house, and his parents were totally cool when we had everybody over. We had people who were well to do, coming from a lot of money, and people who were living over by Maryland and Drexel, which within the Hyde Park subculture was kind of the low end. I can’t imagine parents just allowing that to happen in most parts of the city. Even when I lived in the city, I felt tension just from walking down the street in some areas because of the stigmas and the stereotypes. That was all just thrown out of the window around here.

What was the hip-hop scene in Hyde Park like at that time? Was Stony Island out there yet?

SV: I’m so happy you mentioned that. Rest in peace, Attica. He was a friend of mine who passed away way too young. He was one of the members of Stony Island, a legendary graffiti writer, and just a hip-hop head. He said: “You don’t know about Rakim?!” And then he played it and I just lost it. I was like, “I have to rap now!” That was it.

It was him and another friend of mine that put me up on De La Soul, even, and encouraged me to tune into WHPK more. I think what was instrumental to me getting more into hip-hop—beyond just Run DMC, the Beastie Boys, and LL Cool J—was WHPK. You had people like JP Chill, Chilly Q, and Ice Box. They were the pioneers of that station. They played hip-hop I’d never even heard before. Early on, I was able to get stuff that people anywhere else were never able to. Just being on the South Side, you know, their transmission was widespread. You could get signal. Even in the hundreds, you could get WHPK.

What was your background in music before you guys started producing hip-hop?

MP: I guess my first love is jazz. Growing up, jazz is what we listened to; that’s really what got me into hip-hop. The first CD that I really got into was Stan Getz and the Oscar Peterson Trio. My dad is a professional pianist, but he does more weddings and Bat Mitzvahs. He would always be playing jazz, though, would always be playing the piano. So when I would hear Miles Davis being chopped up, when I would hear these certain sounds like on Guru’s “Jazzmatazz” albums, there was just a direct connection.

SV: My dad used to play the trumpet—he’s from New Orleans—and when he came to Chicago he was in this group called Black Lightning. They were on MCA Records for a second with some guys from the Chi-Lites and Earth, Wind & Fire. When he was finally out of the music game he became Mr. IBM and left me with his horn. My mom was always playing records super loud: Al Green, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder. I started to emulate those guys and their performance. My grandma was also a classically trained pianist, so she was playing in church, and growing up I’d hear her practicing.

When I first really got into hip-hop, it was coming out of the “we’re going to sample everything James Brown” phase. And so that was really exciting. So I got really into jazz and funk, of course, but also groups like Steely Dan which I probably wouldn’t know much about if it weren’t for hip-hop. Now I’m into taking it further: Talking Heads, a lot of retro eighties and late-seventies stuff, Frank Zappa.

I always try to do things that no one else has really done before. So much so that I actually worked in a music library when I was down in Champaign at U of I, because I wanted to have access to stuff that I never heard. I just became obsessed with it. I’m an avid record collector now, just trying to find stuff that’s never been used.

You’re both incredibly active outside the hip-hop scene as well; can you tell us about the mentoring programs that you’ve participated in and how you got involved in them?

SV: It was serendipity, that’s the best word I can use, because when I finished grad school I was working for the Chicago Public School | University of Chicago Internet Project. That was when they were installing programs and computers for teachers to use in their classrooms. There was a kid who was in the seventh grade, as a part of a computer club, and he was class clown but a bright kid.

It wasn’t Ray, and I’m not going to put the school on blast, but when he transitioned to eighth grade I noticed a change in his behavior. He started using crack cocaine and selling crack cocaine. He had this obsession with the Clipse, and I asked him what was it about them. That was when they had their song “Grindin’,” and that was really out and poppin’, and it was before the onslaught of 50 Cent and everybody else that came right after. And he was like, “It’s the beats, Mr. Simeon, them beats, you know!”

I knew it was the Neptunes, and I know Pharrell’s killin’ the music game right now still. But I realized how music had an impact on kids more than anything I’d ever seen before. At the time I was at a crossroads because my group—the Primeridian—had deals on the table for two songs. One was called “Mandingo” and one was called “One Night Stand,” and these songs were adult themed. I realized that if we rode out with the momentum of those songs, then that’d be on the radio and it wasn’t going to be adults hearing it, it’d be kids. It wouldn’t be cool. I didn’t want that on my soul. That’s why I just kind of did a life change and a metamorphosis and realized I wanted to do music production workshops. I took a pay cut. It was a life change. It was needed—if I don’t do it, who else is doing it?

MP: Again, for me it was my cousin Horace Hall—the person who showed me all the records for this album. He started a program called the R.E.A.L. Youth Program. R.E.A.L. is an acronym for Respect, Excellence, Attitude, Leadership. The kids actually came up with it themselves. We instill values through catharsis, letting them do the art that they want to do and using that to implement good values.

One day, I’m down at engineering school getting my degree and all that good stuff, and I come back in town and call Horace. He’s like, “Yo, I’m over with these kids. If you wanna come hang, you can come hang.” Those kids attended prospective charter schools at the time. We’ve put out three CDs with the kids and just…for me the profit’s in the heart. We’ve been doing it since 2001. I was always raised under “get yours and give back.” So that’s my little piece of giving back.

If you could share some advice with young, up-and-coming Chicago rappers and musicians hoping to make a difference through their art, what would you tell them?

SV: Really, really go hard at it. Not just writing every day and rapping every day, but also maybe freestyling so that your flow is impeccable and solid. Know your history, and know that Kool G Rap was one of the best rappers out there at one point because he set these patterns that people are still trying to decode and figure out now. Just have that overall appreciation for it so that you can keep pushing it forward and innovating.

MP: Figure out why you’re doin’ it. Why you love it. And note that nobody’s going to take you seriously unless you take yourself seriously first. If you’re fifty-fifty or if it’s just cool: don’t. It’s not worth the money. It’s really not. One in a billion get enough money to be up there and rich like that.

This story has been revised to reflect the following corrections:

Correction: February 19, 2014

Due to an editing error, the print version of this story misspelled the name of Englewood rapper Pugs Atomz.

Correction: February 20, 2014

An earlier version of this story misstated the age of Simeon Viltz; he is five years older than Mulatto Patriot, not ten. His grandmother, not his mother, was a classically-trained pianist.

Alright Simeon!

Great story on how this incredible album came to creation. BIG ups to MP & working with Chicago youth through mentoring!

Simeon is definitely a local legend.