Maséqua Myers first walked into the South Side Community Art Center at the age of sixteen. It was in this Bronzeville brownstone that she first took African dance classes, in addition to literary and poetry workshops. Myers went on to become an actress and director, performing in Chicago venues like the Victory Gardens Theatre and the Goodman Theatre from the late sixties through 1982. She also served as one of the first teaching artists to work in Chicago Public Schools through Urban Gateways. She and her husband took a twenty-five year break from Chicago to direct, produce, and perform in Phoenix, Arizona and then Los Angeles before family responsibilities called them home to the South Side. Late in 2014, Myers was asked to become the new Executive Director of the SSCAC. The Weekly spoke to Myers on the Art Center’s third floor and production space, just two days after the opening of their first exhibit of 2016, titled “Bridging Generations: Strong Men Getting Stronger.”

In honor of Black History Month, Maséqua Myers, Executive Director of the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), has curated a small series of images from the Art Center’s collection to celebrate African-American history, African-American art, and the South Side Community Art Center’s role in preserving that legacy. On February 8, the SSCAC announced that it won a $300,000 grant from the Alphawood Foundation.

(Oil on Canvas) 1995

Keith Conner is a traditionalist; he has exhibited here in the SSCAC at least once before, but it’s been years. He paints portraits and landscapes, and he loves to expose the art community—art collectors and art appreciators alike—to African artifacts. He uses many themes that deal with love and bringing the importance of loving yourself into his works of art. And we can see many of his works here at the Art Center now.

Conner has been painting all of his life. He’s one of those lucky artists to make a living only as an artist. He has exhibited in places like the Museum of Science and Industry and the Chicago Cultural Center, and he has been responsible for creating film strips and illustrations for Miller Brewing Company, as well as Black History Month illustrations for Central City Productions on WGN-TV (if you remember those programs from back in the day). He also free-lanced with the Encyclopedia Britannica. He’s won awards as well, the latest one being the Artist of the Year Award for Visual Arts from the African American Arts Alliance of Chicago in 2011.

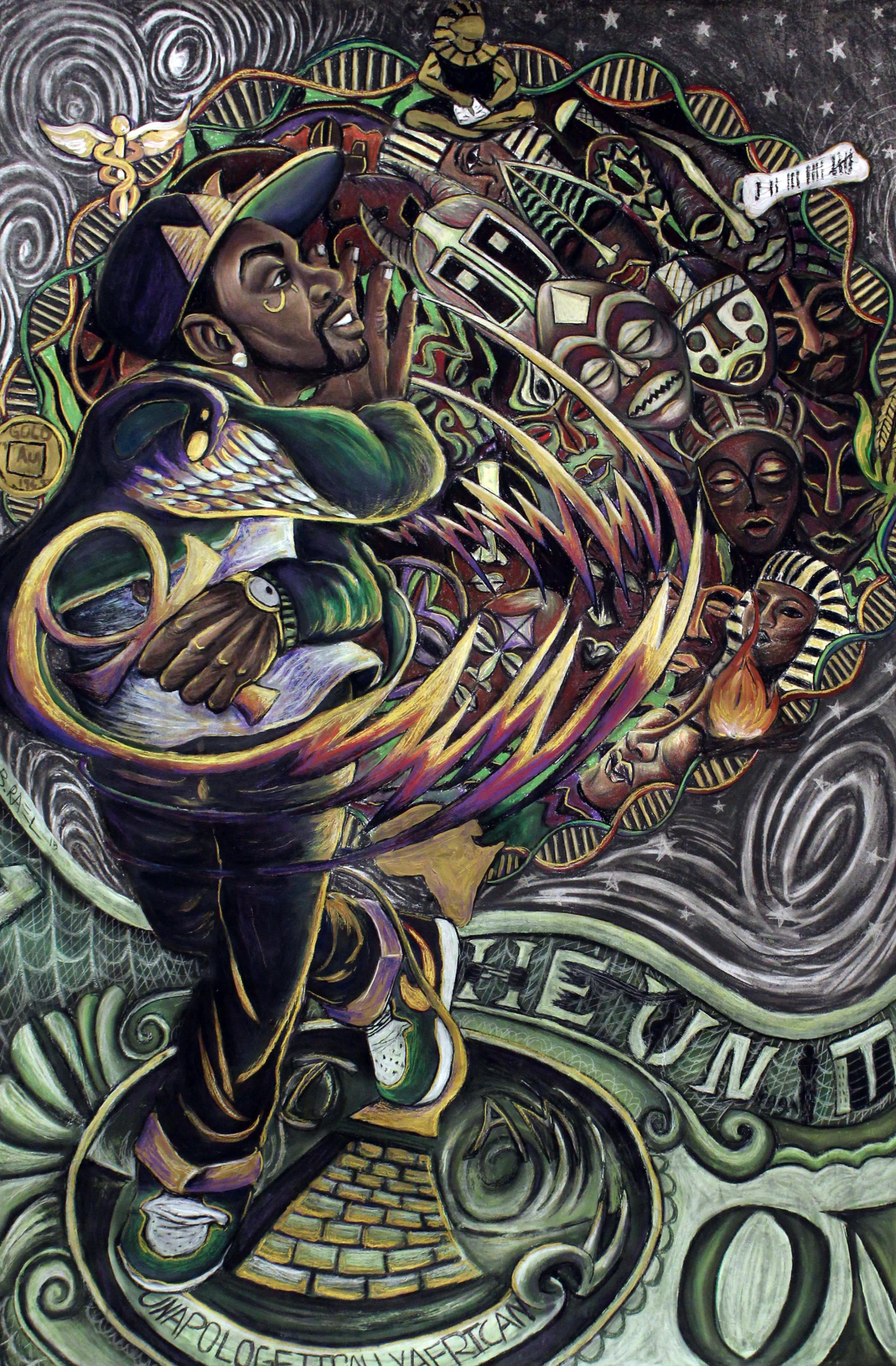

Our last artist is B. Ra-El Ali. He’s a fascinating young artist, mainly because he is so industrious—he has his hustle on. He really knows how to hustle well. And there’s good hustle and there’s bad hustle: he’s a good hustle. He’s a recent graduate of Southern Illinois University with a BFA in painting and drawing. What he did was get out and network—he hit the ground running. He has gone to every art gallery that he thinks would be welcoming, as well as those that would not. He’s just making himself known as a young emerging artist. I like the fact that he has such self-initiative.

Ali works as a mixed media artist because he works in charcoal, acrylic, and oil, and he works on paper most of the time as opposed to canvas or linen. He calls his style of work Afrofuturism. It just means that in just one painting he has layers of three aspects: he uses African symbols and images, adds in American symbols and images, and blends them. And some of these wonderful backdrops create a futuristic approach; they’re combinations of styles and clothing and dress that we’ve never seen before.

(Acrylic) 2008

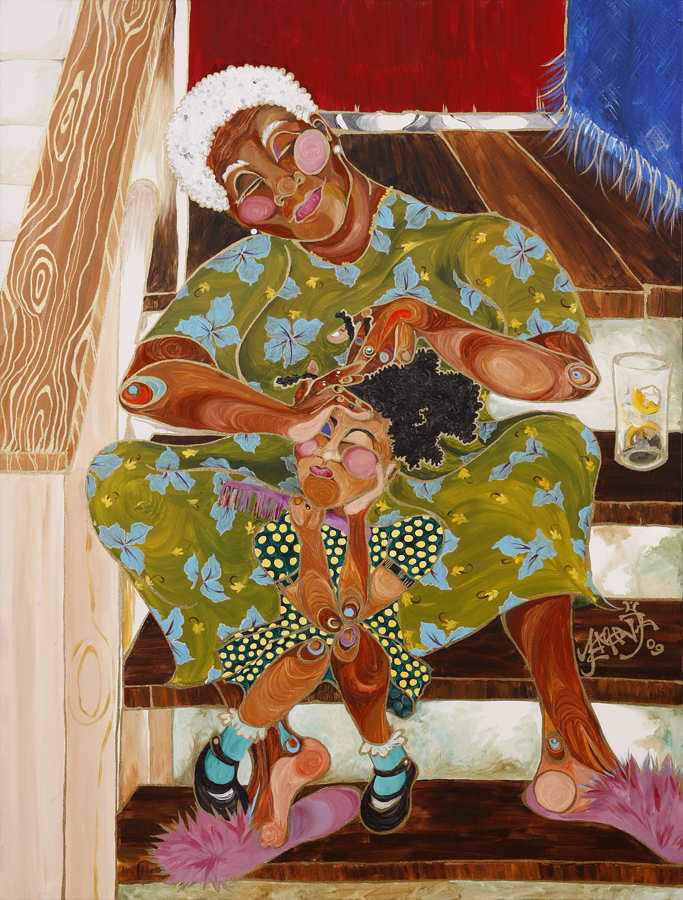

Yemonja Smalls is a clinical psychologist who uses art as therapy, so she’s actually an art therapist, and I smile whenever I visualize that picture. Art often makes us feel better. It really does. And that’s why it’s so important to involve ourselves in art. It can take us away from negativity, from depressing moments in our lives. Art can be motivational, too; it can make us angry, it can fuel other emotions—but so often it’s a feel-good thing.

Dr. Smalls works in acrylics, and she works in circles, if you can see that—it’s like circles. And she creates her images, her faces, her ankles, her feet in circles. It’s just amazing artwork. And she works in bright colors. I love the feel-good feeling that you get from Dr. Smalls’s work. She’s a self-taught artist! Sometimes the best creativity comes from a self-taught, informal situation. It’s good to expose yourself to as much knowledge as possible because you don’t know what else will come out of your creative well. But she’s a self-taught artist, and I’m glad she taught herself. She’s so unique.

This is braiding. This is a really—well maybe it’s in other cultures too, I just know it’s in mine—but it’s a wonderful bonding in African-American culture to braid hair. So this is a bonding moment between a grandmother and a grandchild while she’s braiding and combing her hair. I know it’s a warm, warm thing. So she teaches an African-American tradition and shares it with the world through that painting. (Maséqua Myers)

(Oil on Canvas) 2013

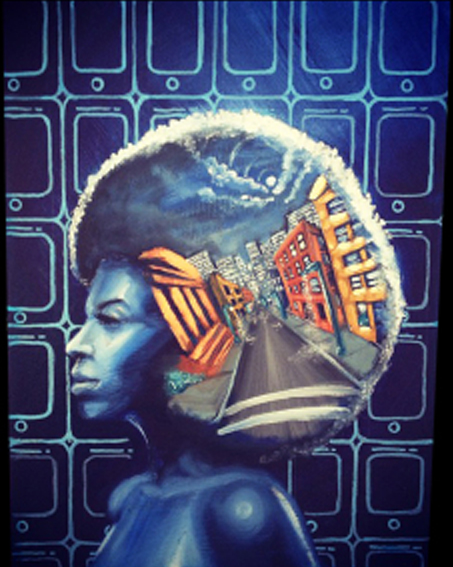

Rahmaan Statik calls his art “liberation art.” Rahmaan Statik started as a graffiti artist, a street artist. And he was introduced to the South Side Community Art Center—this is why we have to stay alive—as a twelve-year-old. He’s now in his early thirties. But he is one of the most sought-after muralists here in Chicago. He has murals throughout the city.

He’s also very kind to the African American female; he understands the importance of the female teaching, and so what he does is a lot of portraits of women from neck up, or bust up. He always incorporates the multi-level or the economy that African Americans often find themselves in which is, “How do I hold on to my African heritage and also love all what I can about my American heritage and experience and blend those two?” and “How then do I ensure that I see myself in the future?”

He’s a very conceptual artist. And as you can see, he’s used the afro—which is kinda coming back, I’ve seen a lot of it. I say “Wait a minute, am I back in the sixties and seventies or what?” And that’s okay, because what doesn’t go out of style is who you are. And so, if you want to be as the creator made you, as God made you, then you should have that right. And so he draws women often in their natural state of hair. And within that hair he puts memories, and he puts projections, and he puts aspirations. (Maséqua Myers)

Joyce Owens is a graduate of Howard University for her undergraduate degree; her master’s was at Yale University. [Until recently she was] a professor of art at Chicago State University. She works with oil on canvas, but the piece we’re talking about here is her sculpture, which is wood and metal. And what she does is take; the reason why I love her is because she takes what some people might call trash, or different objects that are thrown away, and creates the art that we see. So she’ll take pieces of wood that have been thrown out. She’ll find buttons and steal pieces of nails and thumbtacks—all these types of what someone has thrown away and can’t use—and create this beautiful piece of artwork and sculpture, and that’s one of the reasons why I chose her. (Maséqua Myers)

Joyce Owens is a graduate of Howard University for her undergraduate degree; her master’s was at Yale University. [Until recently she was] a professor of art at Chicago State University. She works with oil on canvas, but the piece we’re talking about here is her sculpture, which is wood and metal. And what she does is take; the reason why I love her is because she takes what some people might call trash, or different objects that are thrown away, and creates the art that we see. So she’ll take pieces of wood that have been thrown out. She’ll find buttons and steal pieces of nails and thumbtacks—all these types of what someone has thrown away and can’t use—and create this beautiful piece of artwork and sculpture, and that’s one of the reasons why I chose her. (Maséqua Myers)

I came to the South Side Community Art Center as a sixteen-year-old. I met people who are now so renowned in Chicago, like Haki Madhubuti—formerly known as Don L. Lee—and Gwendolyn Brooks. Gwendolyn taught classes downstairs, and she would sit at that piano that’s down there and get inspired by the environment to write. It’s wonderful to feel the spirit of this place because there were no other places that African Americans could experience what they experience here, because of racism.

There were no galleries that allowed African Americans to hang their artwork, and so it was founded for a need to have a place to create, to develop, and to share artistically. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Arts Project was very helpful in making this happen. What the WPA initiative did was to hire instructors, so they were paid salaries. As a result of that we were able to offer classes free, and the community was able to come in and enjoy the expertise of renowned artists without having to pay. That was quite a service to the community, and we attempt to do that still. We make classes very affordable, if it’s not a free experience, and that’s part of our history as well. We have never closed our door in seventy-five years, so we’re very proud of that.

I came here to continue this legacy. No, it’s not a career advancement, but it’s a calling. It’s a mission. I want this place to survive another seventy-five years of existence, because it’s quite motivational, inspirational—especially for those who say they’re going to be artists for a living, be artists for a career. And to be able to reaffirm that that’s okay, that that can happen, makes all the difference in a young person’s life. They get focused, they understand that “If I work really hard, if I educate myself very well, if I sell, if I seek new experiences that give me a well-rounded persona and base to create from, then I have a lot of potential and a lot of opportunity.” That motivation comes from places like the South Side Community Art Center, and since I was inspired that way, I want it to be the same for any other person that comes in these doors.

I believe in this mission. It’s really important to have a creative outlet in the community for so many reasons. One of the major reasons for me is because young people, especially now, don’t have many places to go that are creative and constructive. I would rather see them with a paintbrush than with a weapon in their hand. And if they can get introduced to an environment that pushes that, that’s what happens. I was affected like that as a teen.

Just yesterday I had a fifteen-year-old, come up to the door, take pictures of the public hours signs outside the door. I found out she lived right across the street and she’s an aspiring artist. She had been wanting to come in but she wasn’t sure if she should, so I went out and talked to her. She was inspired. She wanted to know if, indeed, one day if she could have her art on the wall. And I said, “That’s why we’re here. We’re here for you.”

The South Side Community Art Center’s mission is to preserve, conserve, and promote the legacy and the future of African-American artists while educating the community of the importance of art and culture. And our first exhibition of the 2016 season, I believe speaks so well to that. The name of the exhibition is “Bridging Generations: Strong Men Getting Stronger.” “Strong Men” is a poem written by Sterling Brown in 1931, and that was one of his poems that was motivational for me to curate this show.

We’re in a time, presently, where we are talking more about the violence towards black and African-American males: violence towards them by each other and violence towards them by society, and particularly law enforcement. I wanted to be able to stimulate dialogue about the importance of having inner strength and focus to do the right thing. I wanted to give focus to the need to understand that there should be a connectedness with the generations. It’s an African tradition, and it’s an African-American tradition that I don’t believe we should lose sight of.

With these three artists, we have Millennials, Generation X, and then the Baby Boomers, so we’re showing three generations that connect through the art because they draw images that are similar in concept, maybe not in style, but in concept. These three artists understand the importance of knowing your history, where you come from, what your African heritage is; then they know the importance of our American experience, and combining those two helps us to project ourselves into a wholesome future. Not knowing one or another leaves an emptiness, leads to a possibility of not understanding your total importance and worth. (Maséqua Myers)

“Bridging Generations: Strong Men Getting Stronger” will be on display at the South Side Community Art Center through April 9..

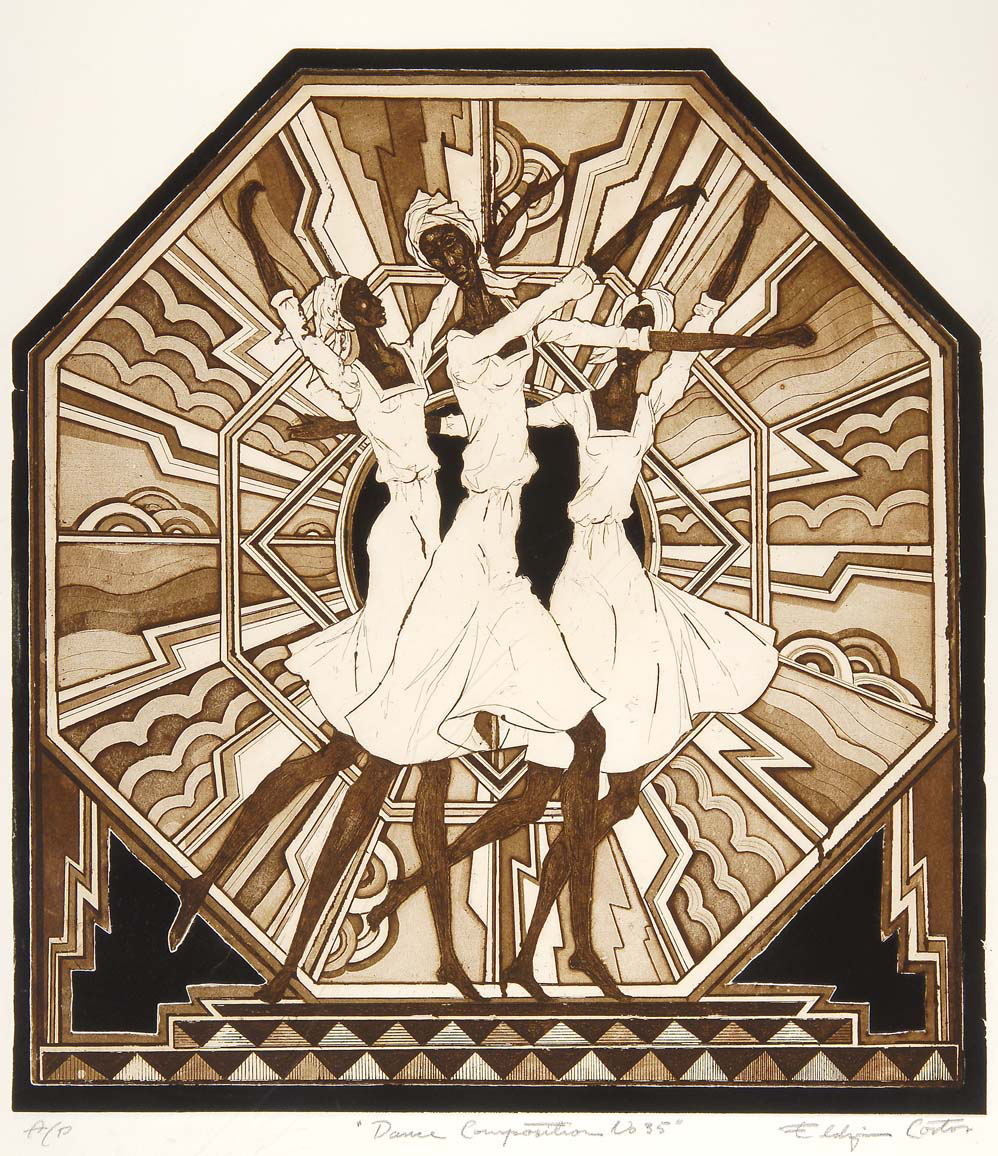

I’ve put the two longest-living founding artists together. Eldzier Cortor is the most recently deceased founding artist of the SSCAC; he was the last living founding artist. So he’s what I call our ancestor. He drew realism, abstractions—he was quite diverse. He was a Guggenheim awardee, and that award took him to places like Cuba, Mexico, Haiti. People were just in awe of his ability to capture the environment he saw. He graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1936, around which time he saw an exhibition at the Field Museum of West African art, and loved it. He wound up combining the West African art with European Impressionism; with that he created a different image of the black woman. As you can see in this particular painting, he created an image of grace, of dignity, and of strength. And he did that by elongating the neck and the limbs, giving a graceful, beautiful, dignified persona to the African-American female.

Tony Smith

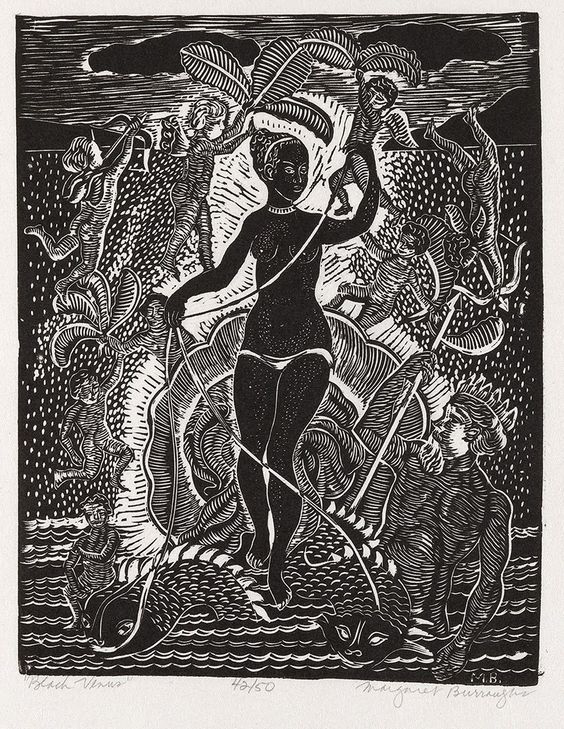

I chose “Black Venus” because of how important women have been to the founding and the continuation of the South Side Community Art Center, and how important the female is to the grounding of family and to spreading love, nurturing. We often set the moral guidelines of a society, we set moral guidelines in our families, and so in this piece, she’s holding the child up, because we are the teachers of the next generation. We are the first teachers of life, to our younger generation, to those that we bear, so that’s why I chose that.

Dr. [Margaret Taylor Goss] Burroughs was always a serious person, even as a young person. She was the youngest to ever sit on the Board of Directors of the South Side Community Art Center at twenty-three years of age; she gave seventy years of her life to the continuation of the South Side Community Art Center. She wanted to raise the quality of life for African Americans because she was born in 1917, a difficult time for the representation of African-American people. When she travelled outside of the country, to places like Africa, she was so uplifted by the difference in the beauty standard outside of America. She wanted to come back and show people just how proud they can be of themselves, how beautiful they can be, and even though she wanted to teach self-love to black folk, she wanted everyone to understand the beauty of African heritage.

Dr. Burroughs was my Humanities 101 instructor at KennedyKing College, so I have a long history with her. I met her when I was about sixteen and started taking classes; I began dramatically reading her poetry all over the city. One of the poems was “What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black?” It’s a lovely poem, and Burroughs talks about all of the negative ways the color black is used for before writing, “I will tell them about their history and how much they can be proud of.” What she taught me was that you didn’t have to hate anybody else to love yourself; in fact, you have to really love yourself before you can really love someone else and appreciate someone else. She taught self-love without self-hate. (Maséqua Myers)