The Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA), a civilian police oversight body established by City ordinance in 2021 that is set to ramp up later this year, will have legal powers to request information about police activities from the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) and the Chicago Police Department (CPD). Such requests will be similar to those the public and journalists can make through the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which allows anyone to ask public agencies for data and documents.

But FOIA requests in Chicago often run up against denials of varying legality. The CCPSA may find its requests similarly held up by one of the City’s most abused reasons for denying the public access to information: if the commission requests records tied to an ongoing investigation, the City can deny access to those records.

While it’s difficult to predict whether the City will deny the committee access to information, its history of withholding information in consistent violation of the law may be the public’s clearest view into how CPD will respond to the Commission’s requests for information.

The CPD is by no means shy in denying the public access to information about its operations, and often cites ongoing investigations in doing so—often with dubious reasons and scandalous outcomes. In 2019, Anjanette Young submitted a FOIA request for footage from body-worn cameras (BWC) of the police officers who wrongfully raided her home earlier that year. The police department’s FOIA office denied Young’s request because an investigation of the raid was ongoing.

Young ultimately filed a lawsuit to compel the department to comply with her FOIA request.

To understand whether the denial of Young’s request’s was a rare one-off, or one that typifies the Chicago police department’s approach to FOIA requests, the Weekly pored over hundreds of FOIA requests that the CPD denied based on legal rationalizations similar to those cited by the department when it denied Young’s.

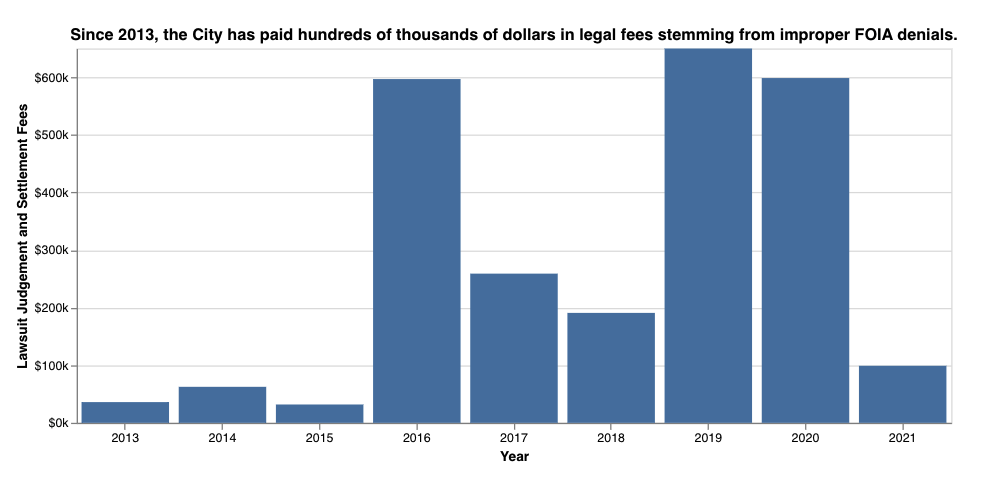

This research adds to an ever-growing body of reporting and litigation surrounding the City’s flagrant disregard for the transparency mandates it’s required by law to follow.

The Illinois FOIA allows certain records to be exempt from disclosure, and describes such exemptions in section 7(1) of the law. Some examples include: private personal information in section 7(1)(b), documents related to ongoing investigations in section 7(1)(d), and administrative proceedings in section 7(1)(n).

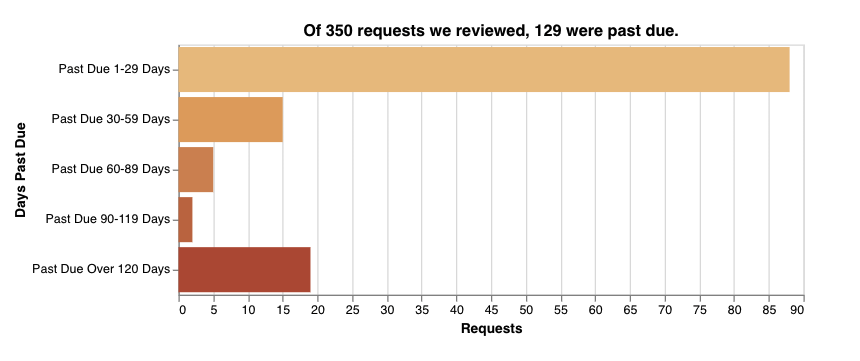

I reviewed 350 FOIA requests that were denied by CPD under 7(1)(d), the portion of the Illinois FOIA that deals with ongoing investigations, between January 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021.

When I submitted a request for all such denial letters, the department initially argued that identifying requests denied under 7(1)(d) would be unduly burdensome, meaning it would overwhelm their office with the work required to fulfill it.

One reason that the request was considered “burdensome” stemmed from a limitation in the police department’s FOIA tracking software that only allowed the recording of one denial reason, while requests are often being denied with multiple exemptions. The only way for CPD to find all requests denied under 7(1)(d) was to review all denial letters sent during the timeframe on the chance that 7(1)(d) was used in addition to the exemption recorded by CPD in their tracking software.

To compel CPD to keep track of all exemptions for all requests going forward, I am currently suing CPD, arguing that CPD is in violation of FOIA by not making an index of exemptions used in requests public, as required by the law.

Since the start of the lawsuit, CPD has updated their software to allow it to track more than one exemption per request.

The problem seems common; I requested a log of all FOIA requests and an index of exemptions from all thirty-six agencies listed on Chicago’s FOIA contacts page, and only seven agencies shared the exemptions they used.

The analysis in this article covers the time periods between 2020 and early-mid 2021.

Four months after the request was submitted, CPD completed the request and provided 286 requests. To cover the time periods after Mayor Lori Lightfoot promised to make it easier to request BWC footage, in October 2021 I requested all requests denied under Section 7(1)(d). CPD again argued that it would be unduly burdensome to release that many documents and we agreed to narrow the request down to January 1, 2021 through April 1, 2021. Once we provided the narrowed request, CPD completed it in under a week.

Through one of the most common reasons for denying FOIA requests, an agency can deny access to records as “unduly burdensome” if completing the request is so time consuming that it prevents the City from doing its day-to-day work. The common exemption has its limitations to prevent its abuse by government agencies, including losing access to the exemption if the City doesn’t respond within five days—as happened with Charles Green’s FOIA request that led to the release of tens of thousands of misconduct investigations.

Additionally, the law prohibits the City from claiming an unduly burdensome exemption in cases where there is “overwhelming public interest” in the records that outweighs the cost to the City of reviewing them. The law also requires the City to provide “clear and convincing evidence” supporting any assertion of the contrary.

CPD showed a deep disregard of the public’s interest and press access to information for two 2020 police shootings that sparked major protests across the city. Despite the unmistakable public interest in both police shootings, CPD denied all requests for body-worn camera (BWC) footage of them, arguing that reviewing the footage in preparation of releasing it would be unduly burdensome. The news organizations that were denied the footage included The Chicago Reporter, CBS 2, the Sun-Times, WBEZ, ABC 7, WGN-TV, Chicago One Media, and NBC 5.

Merrick Wayne, an attorney at Loevy & Loevy, has litigated many FOIA lawsuits against CPD, including my own. He says CPD hasn’t followed the law when it used the “unduly burdensome” clause to deny these requests because the department didn’t estimate how long the review would take and didn’t show how the cost of reviewing them would outweigh the public interest in seeing them. Wayne adds that by not providing opportunities to narrow the scope of such requests, CPD waived the legal use of the unduly burdensome exemption. In their denials, CPD argued there was no way to narrow those requests, but failed to say how.

During my investigation with Matt Harvey for the TRiiBE, of one of the two shootings, CPD also denied a request for logs from ShotSpotter devices, citing ongoing investigations. Despite its denial, two months prior to the TRiiBE’s request to CPD for ShotSpotter logs, COPA released videos that contained the same information CPD had denied—audio of the shooting from multiple cameras in the area.

The TriiBE escalated the request to the Illinois Public Access Counselor (PAC), which hears administrative appeals of FOIA denials. CPD responded several weeks later with ShotSpotter logs, over three months after the request was submitted. The document provided describes fewer recorded shots than what police officers claimed in reports they filed.

However, even though COPA released the video from that police shooting, the City continues to fight a lawsuit that was filed in September 2020 seeking the same footage. Attorneys for CPD filed an appeal in July 2021 that claimed the department is not obligated to release the footage. If a government agency denies a request, it has the legal obligation to provide clear and convincing evidence that the information it’s withholding is exempt from disclosure.

This is made clear in the PAC’s FOIA Guide for Law Enforcement, which notes that under FOIA, all records an agency holds are presumed to be open to inspection, and any assertion that a record is exempt from disclosure must include “clear and convincing evidence” that that record is in fact exempt.

The PAC’s Guide goes on to say, “Perhaps the most common error the PAC encounters in reviewing FOIA denials is the failure of public bodies to explain why and how the asserted exemptions apply to the records that they withhold.”

Despite the heavy burden of proof required to deny records, of the hundreds of requests I reviewed that were denied for being related to an ongoing investigation, it was exceedingly rare for the City to provide any meaningful explanation of how releasing those records could compromise an ongoing investigation.

When a government agency exempts information, it is required to review and redact information only if it’s considered exempt under the law. With few exceptions, the agency does not have the legal ability to simply not provide a full document solely because it contains some exempt information. It must redact only the exempt information, and disclose the rest of the document. The PAC’s guide for law enforcement is clear in this regard.

In my investigation, I found five requests that were denied even though the associated investigations had already been closed, or cited an already-passed court date. Similarly, I found forty-two requests that were denied simply because they were associated with a filed complaint against a police officer that is still under investigation.

In one instance, CPD denied a man in prison access to video and audio records, arguing that providing the records as a CD would have endangered the physical safety of others. The denial gave the man no option to view the requested media without a CD.

According to records from CPD, of the 7,196 FOIA requests sent to CPD in 2020, 1,469 of those were marked as closed thirty days after they were submitted, with around 300 taking longer than 100 days.

If an agency doesn’t respond to a request in the legally mandated time frame of five to ten business days, it then loses the ability to claim that a request is unduly burdensome, regardless of how long it would take to complete the request. This places a strong requirement on the city to respond on time. However, of the 350 requests I reviewed, around forty percent were completed after the time limits allowed under state law, with twenty of those taking longer than 120 days to complete.

It’s unclear whether any agencies intentionally delay responses to FOIA requests as routine habit, but an email from the Jones Day email hack shows at least one request where the City intentionally delayed responding. And last year, the Department of Law’s FOIA log showed that the City again delayed its response until the last possible time, noting to “wait to respond until due date.”

CPD denied access to requesters looking either for rosters of CPD officers assigned to schools as school resource officers (SROs), or records related to a school’s assigned SROs, arguing that releasing the records could endanger the lives of the officers assigned to a school. As with a majority of CPD’s denials, it provided very little detail explaining how the release of the records could endanger the SROs.

In one denial, a requester was denied access to the misconduct records of police officers stationed at Hyde Park Academy simply because the request “encompasses information related to the security measures put into place by CPD in conjunction with the Chicago Public School System to prevent as well as respond to potential attacks upon the school community population.”

Merrick Wayne at Loevy and Loevy called the citations “sweeping and generic exemption claims” that give no factual basis about how releasing SRO names puts SROs, or anyone else, in any danger. He added that even if the records contained exempt information, CPD must still provide all other non-exempt information, which it did not do.

CPD additionally denied access to information from forty-five requests for defendants in criminal trials, arguing that the release of the respective records “would clearly jeopardize the fairness of the ongoing criminal trial.”

Despite its legal requirement to provide “clear and convincing evidence,” none of the forty-five requests explain how the release of those records would jeopardize fairness as required by law, and simply points to a section of the statute without any supporting information. In four of the denial letters we reviewed, the court date mentioned in CPD’s denial letters had already passed.

“CPD is merely reciting the statutory language, which Illinois courts routinely reject,” Wayne said. “The response letters fail to explain how disclosure of any portion of any case incident report or even a person’s own mugshot would create a substantial likelihood that a person would be deprived of fairness at their trial or interfere with any proceedings. CPD’s denials seem to imply that if CPD arrests a person, the only way to have a fair trial is to prevent that same person from accessing their own records.”

It’s difficult to say whether CPD will continue its patterns of non-transparency in the years to come. Frank Chapman, a community organizer who was key in pushing for the Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability, said he is cautiously optimistic.

“We’re in a new set of circumstances,” Chapman says. “CPD has an opportunity to act accordingly. They have an opportunity to gain trust with the community and the [Empowering Communities for Public Safety ordinance].”

But significant work is still needed to show that the City has a legitimate interest in being open and transparent. The extensive efforts needed to review their transparency practices are made much more difficult by a lack of adequate tracking of information about how requests are handled, with very little oversight or repercussions when consistent FOIA violations occur. To date, the Office of the Inspector General has yet to review any of the City’s FOIA practices.

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Matt Chapman is a researcher in Chicago who focuses on issues of transparency and policing.