I have a shout—”

“—OUT,” the room called back.

Ninety people had filed into a small room in the South Shore Cultural Center for a workshop on the history of Black and Latinx farming movements, one of the morning’s first workshops at the thirteenth annual Chicago Food Policy Action Council (CFPAC) summit last Friday.

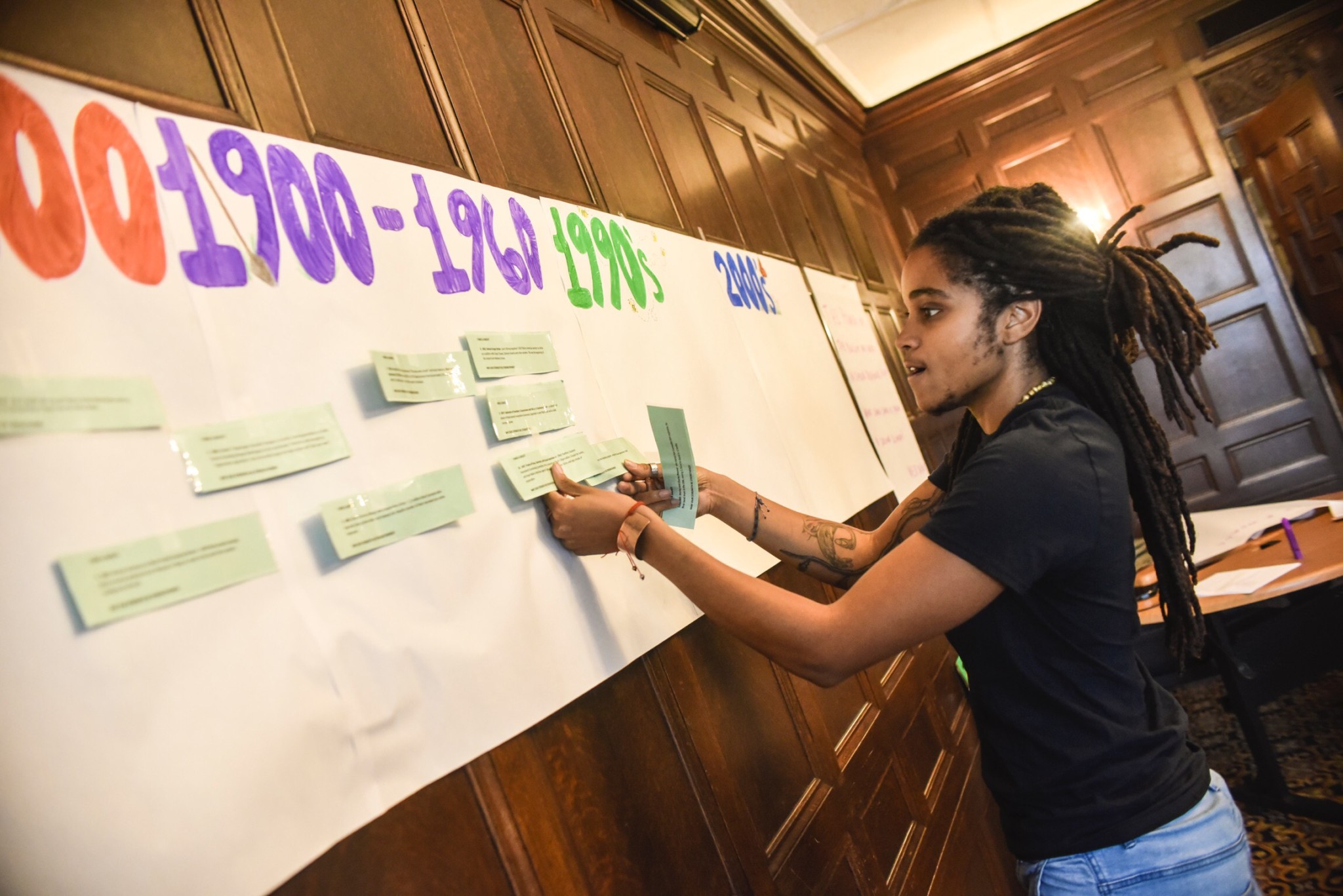

For the first thirty minutes, the workshop took a call-and-response format. Participants were given green slips of paper, containing a sentence about an organization, movement, or event important to Black and Latinx farming movements, to read aloud in English, Spanish, or both.

“1969: Shirley and Charles Sherrod started the New Communities farm cooperative, the first land trust in the U.S.A., owning 5,700 acres shared by twelve families.”

“May our strength be strengthened,” the room responded.

The workshop leaders gathered each slip, taping them onto a timeline that stretched from 10,000 BCE to 2017 at the front of the room. The first slip honored African women who braided the seeds of barley, sorghum, okra, and more into the hair of their daughters and granddaughters before they boarded transatlantic slave ships. Other slips recognized the role of Tuskegee University in the sustainable farming movement and the organizing of the United Farm Workers union by Dolores Huerta and César Chávez.

The last slip posted on the timeline brought it home to Chicago, celebrating the passage of the Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) in 2017—a city council ordinance that requires city agencies to contract with local food providers with strong labor and environmental practices, healthy products, and a track record of animal welfare practices. Among other significant changes, the GFPP will be able to provide leverage against the exploitation of Black and Latinx workers, who are disproportionately impacted by wage theft and discriminatory hiring practices in the food industry.

2017 was a momentous year for food justice advocates, and there was much to celebrate at CFPAC. In addition to the passage of the GFPP last fall, CFPAC chair member and Urban Growers Collective CEO Erika Allen held up the Urban Stewards Action Committee, a new collaboration between food justice leaders in Little Village and Englewood, as one of the most promising outcomes of the past year.

CFPAC works on a grassroots level to formulate and promote justice-oriented food policy. Over the course of the day, leaders from CFPAC and other organizations—Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, the Urban Growers Collective, the Asociación Vendedores Ambulantes, and the Centro de Trabajadores Unidos—came together to strategize about the problems farmers and foodworkers are currently facing in Chicago: how to uplift new farmers, especially farmers of color, how to organize worker cooperatives, and how to establish the wording for a new urban agriculture license.

The leaders of the first workshop were neither the first nor the last to hone in on the importance of racial justice and historic farming movements to food justice. In the keynote speech that kicked off the summit, poet, educator, and farmer Amani Olugbala talked about grounding her work in appreciation for earlier generations of farmers and activists from the perspective of reparations and land justice.

“When we’re talking about the food system, it’s built on stolen land, not just stolen labor,” Olugbala said, acknowledging the thousands of Potawatomi and Illini people forcibly removed from the Chicagoland area. “And when we talk about justice or progress…we want to make sure we are keeping the original stewards of this land in mind.”

Olugbala is also part of the team at Soul Fire Farm, a farm led by people of color and based in Grafton, New York dedicated to ending racism within the food system and to achieving reparations for farmers of color. As part of their work, Soul Fire runs a subsidized produce share program for community members facing food apartheid (“food apartheid,” because Olugbala and other activists say “food desert” does not adequately convey the agency government officials and food corporations have in perpetuating produce scarcity in Black and Latinx neighborhoods). They also run leadership programs and Black and Latinx farmer immersion programs, which have gained national recognition in the food justice community, and which several CFPAC attendees have participated in.

One program alum, Viviana Moreno, a grower and organizer with Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, received a special shout-out from Olugbala for helping to kick-start Soul Fire’s most recent project: a nationwide map designed to facilitate reparations for Black, Latinx, immigrant, and Indigenous farmers.

“Oppression and all systems that it gives birth to, it doesn’t want us to see ourselves as a community, it doesn’t want us to see ourselves as intimately connected and related to…seeming strangers,” Olugbala continued. “I’m happy that we’re harnessing that and continue to do that [work] the rest of the weekend.”

Organizers and attendees carried forward Olugbala’s intentions for the rest of the day, providing a space for policy to be informed and shaped by recognition of historical injustices and the impacts of racism, and the ways in which sustainable farming techniques and equitable food policies have been appropriated by policymakers. An oft-cited example is the fact that the U.S. government demonized the Black Panther Party for its “radical” tactics, all the while using its free breakfast program—which fed up to 10,000 children nationwide at its peak and was an integral part of the Black Panthers’ organizing—as the blueprint for its own free breakfast program.

After the call-and-response session during the first workshop, participants broke off into smaller groups according to their role in the food system—producers, distributors, processors, retailers, consumers—with the task of brainstorming policies that could better align the current food system with the needs and interests of communities of color.

The takeaways highlighted areas for increased attention in the coming years: the need for a better distribution system between community gardens and residents, for more cooperatives and worker-owned kitchens to lower obstacles for food processors, and for increased communications between existing farms, schools, and stores in the interest of distributing fresh, local produce in under-resourced communities.

LeRoy Chalmers, a strategic partnership manager for Habitat for Humanity and one of the three workshop leaders, noted at the workshop’s end that there were no attendees who represented the distribution sector of the food industry. “So there’s a gap from farm to table right now…Most drivers are people of color,” he said. “So, why are we missing that [sector of the food industry here]?”

Many of these conversations about equity in representation and access, already ongoing in community organizations across the South and West Sides, continued throughout the day. To this end, for the first time in its history, CFPAC provided translation services on site, allowing Spanish speakers to hear real-time translations transmitted through headsets, and to have their comments and questions translated into English. (The latter process was not as smooth, but offering formal two-way translation services was nevertheless an improvement.)

Erika Allen and Jose Oliva, a co-director of the Food Chain Workers Alliance, talked about the need to focus resources on farmers of color before the implementation of GFPP—which may open doors for smaller producers to get city contracts.

CFPAC is lobbying Cook County to pass its own, more progressive version of GFPP, one that includes racial justice and gender justice among the list of priorities when offering contracts to food providers. Already, Chicago is the first city outside of California to pass the GFPP. To pass the more progressive version on the county level would be an exciting step, Oliva said, making Chicago home to the most bold GFPP policy.

In the meantime, however, they’re focused on making sure “the new folks start participating now,” so that the contracts that do open up through the GFPP don’t go to larger-scale and white-led farms and companies by default.

“If we’re not communicating with and commissioning those that are in need, or come from marginalized communities, then we’re just replicating the same system,” Oliva said.

Later, organizers from the Centro de Trabajadores Unidos and Chicago Community and Workers Rights discussed the centrality of cooperatives to workers rights movements, and examined the benefits—and legal difficulties—of being recognized as a worker-owned cooperative in Illinois.

Moreno, one of the organizers of the first workshop, said that when they first proposed their workshop, there was some doubt towards CFPAC about whether a history-oriented workshop would fit into a policy-oriented summit. But more than half the summit’s attendees showed up to talk history, policy, and their intersections in the cramped room on the second floor. On a February morning, even the windows had to be cracked to keep the room at a reasonable temperature.

“To me, it’s clear that we are answering a need,” Moreno said. “I feel like this indicates to me that we can organize ourselves.”

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly