Countless people have seen the enormous Virgen de Guadalupe street painting in Chicago’s La Villita neighborhood—a mural near 26th St. and Pulaski Ave.—that displays a young man kneeling in the foreground with his head bowed in prayer. Drivers and pedestrians can’t miss it, and people from out of state come to Chicago to see it.

The praying man in the mural is the painter himself, Héctor González, shown in his late twenties at the time it went up. Eighteen years later, he is returning to renovate the entire thirty-five-foot piece.

Over the years, he has driven by to see the mural or has sat quietly across the street from it, and said he has been moved whenever people taped flowers to the brick wall or placed candles on the pavement.

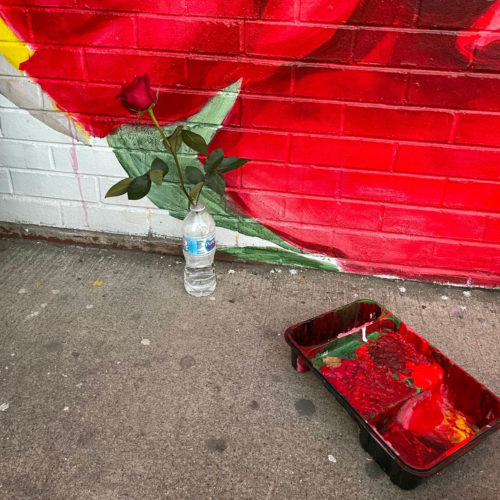

As he was busy repainting it in recent days, a woman stopped by to place a rose in a plastic water bottle in front of the unfinished mural. “She was like, ‘Hey, I want to be the first one to leave the rose for the Virgen,’” he recalled.

González was born in Mexico City and his family settled in La Villita when he was six years old. He was exposed to the arts after visiting the classic colossal murals found throughout the Mexican capital as a child. In Chicago, he joined an aerosol crew that did large-scale pieces on public walls across the city, leading to a career fabricating professional artworks and installations for artists all over the world.

All this time, González led a private life and seldom spoke about the public artwork despite its popularity. But now he’s opening up and sharing the story behind the Guadalupe mural, one that is also a story about himself.

He was already a renowned street artist in the early 2000s, known locally by his graffiti name “Disrokone”—when he went through a catastrophic and transformational period in his life. His then-girlfriend, Gabby Martínez, was diagnosed with cancer and he was one of her caretakers until her last moments.

Before she passed away in 2001, he prayed fervently to La Virgen de Guadalupe, the most reverenced religious icon for Mexican Catholics. “Like Mom,” González described her. “She’s like a motherly presence that has your back. You know what I mean?”

He prayed for a spiritual intervention to endure the imminent loss of his partner. “‘Give [me] the strength that I need to be there for her. And to survive this,’” he remembered praying. “‘I don’t know what I can do, or how I can give this favor or blessing back to you,’” he’d tell the Virgen. “‘But I’ll do whatever I can to bring people closer to you.’”

The muralist essentially made a religious vow: the equivalent of a manda, as it is commonly known in Mexico, to repay the Guadalupana for her protection during a time of extreme suffering.

In Mexican culture, mandas are usually “repaid” months or years later through a pilgrimage to a shrine—sometimes requiring a trip back to the homeland—that is usually accompanied by an offering of money or other symbolic artifacts for the religious entity that interceded.

About a year or so after Gabby’s passing, he remembered the vow he had made, and he felt the additional urge to give something back to the community that raised him.

He noticed that La Chiquita Supermarket had built a warehouse at its second location in the neighborhood and immediately thought the high-traffic, west-facing wall was perfect for a piece that would be larger than life.

Having had a working relationship with the store owner, Alfredo Linares, after painting the interior of his restaurant, he felt comfortable asking for permission to use the outside wall for something so deeply personal.

“I probably spent like two months painting the original mural, because I was still going through the grieving process. And a lot of it had to do with me…reconnecting and keeping this promise,” he said. “And it was a form of therapy for me, basically. So I dragged out the project.”

Locals always wondered about the anonymous women in the sepia-toned portraits that González integrated into the artwork. “[That’s] my girlfriend’s photograph, and her mom [who] also passed away from cancer,” he said. “And the girl below her, we met her while Gabby was in the hospital. We became very good friends with her and her family. And then when Gabby died, she also died.”

The last portrait is of his late sister, who also passed away from health-related issues.

“The story was very behind closed doors. I mean, even La Chiquita would call me. For years and years, they would call me and they would be like, ‘Hey, Hector, the Catholic magazine wants to put that on their cover and they want to get in touch with you’. And I was like, ‘Nah, no, I don’t want nothing to do with the press about this. I don’t want to explain anything to anybody.’ You know, I just did that for me.”

The owner was always empathetic, and even when a part of the mural got tagged in recent years, he didn’t let anybody retouch the painting.

The muralist has overcome that difficult chapter of his life and now finds himself in a good place. “Life has moved forward. And I’ve learned from everything that I went through and… those challenges that I went through are now the things that motivate me to go forward and stuff, because I saw the preciousness of life, you know, and a lot of people don’t get to see that,” he said.

He considers it a full circle that his current partner, his fiance Anna Murphy, a muralist in her own right, is assisting him with the renovation. His close friend, art instructor Grigor Eftimov, is also helping.

The new version of the mural includes much more color than the previous one: bright reds, greens, and golds.

González is planning a “blessing” of the mural on December 12, the official day of La Virgen de Guadalupe, at 10 a.m., with mariachi.

Jacqueline Serrato is the editor-in-chief of the Weekly. She last wrote a photo essay about the removal of the Jackson Park trees for the construction of the Obama Presidential Center.