This story was originally published by the Illinois Answers Project as part of their series Making it in Chicago: Detours and Dead Ends on the Path to Opportunity.

Around 1938, Marshall Hatch’s father hopped on a train in Mississippi to follow his older sister to Chicago, a city that promised a better life with opportunities that could benefit generations after him.

“They used to say ‘if you can’t find a job in Chicago, you can’t find a job anywhere,’” Hatch said. “It really was like a promiseland.”

He was raised in public housing with seven sisters on his father’s meatpacking salary before going to college, earning multiple advanced degrees, becoming a senior pastor and raising similarly successful children.

His father’s bet on the American Dream paid off big time for the Hatch family.

“It’s an upward mobility story for my family personally,” he said. But he recognizes that kind of opportunity hasn’t been the case for many others, especially those who emigrated to Chicago decades after his father in the 1930s.

“I’ve seen the American Dream, for migrating families, go from a dream to a nightmare,” he said. “There’s a lot of poverty and dysfunction.”

Nearly a century later, Chicago continues to be a place of refuge for migrants from further-flung places like Venezuela, Ukraine, the Caribbean and countries throughout the world. But is it still the land of economic opportunity and possibility? A place where children raised in public housing on a meatpacking salary can go on to become homeowners with good jobs?

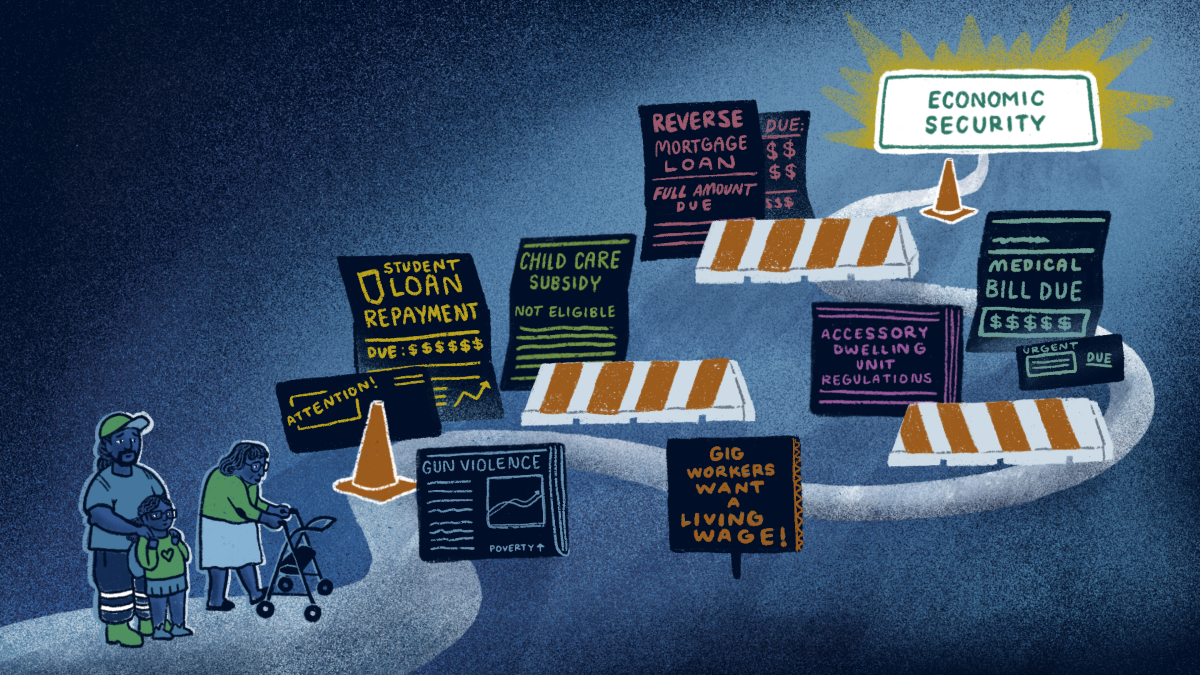

The path to upward mobility, studies show, is paved by affordable and quality education, housing, health care as well as safe neighborhoods and good-paying jobs. But access to those cornerstones is becoming out of reach for more and more Chicago families as the cost of living skyrockets. For example, an individual spent on average $353 a year on health care in 1970. That number is $14,570 in 2023, according to a Peterson-KFF analysis. Even when accounting for inflation, that increase is still more than six times as much.

Between 1991 and 2024, child care costs rose at nearly twice the pace of inflation, according to KPMG. And tuition for college has grown at three to five times the rate of inflation in the last forty years, according to the Chicago Bar Association.

But there are some efforts to help families that could be part of a roadmap to upwards economic mobility.

In one neighborhood, a collection of violence interruption programs may be a key to bringing economic life back to the neighborhood.

A proposal to allow for more coach houses and basement units may offer more options to people looking for affordable housing. And a state program that forgives student loans for people who are buying homes offers families saddled with debt an opportunity to build wealth.

But many of the programs that aim to fix cost of living burdens are limited and underfunded, especially as median salaries are often not enough for basic life needs.

Making ends meet is not only harder due to rising costs, but also due to a lack of well paying job opportunities.

Unlike Hatch’s father, many recent immigrants to Chicago are working as landscapers, nail salon technicians and child care providers, said Lilia Fernández, a history professor at University of Illinois Chicago. National data shows that immigrants make up an outsized portion of the service industry. More than 20 percent of working immigrants were in the service industry in 2023, compared to some 15 percent of U.S.-born working people, according to the bureau of labor statistics.

These jobs are far less stable and well-paying compared to the manufacturing and production jobs of the early to mid-1900s, she said. As industrial jobs moved abroad or disappeared with technological advancement, they were replaced by service, hospitality and retail jobs that are often seasonal, low-wage and part of the gig economy.

“The work may not be as steady and stable,” Fernández said.

The data shows that the gap between Chicago’s wealthiest families and neighborhoods and its poorest has been steadily growing . And where you are born, in a wealthy or struggling neighborhood, has a significant bearing on your success in later life.

The city’s own analysis of census data shows that low-income neighborhoods are also among the least able to advance economically.

Cook County’s wealthiest communities, comprising mostly of the city’s white residents, have more than 200 times more wealth than the city’s poorest communities, which are largely made up of residents of color, according to The Urban Institute, a think tank based in Washington D.C. This wasn’t always the case. Income inequality has accelerated since the 1980s and is growing faster than the federal income gap, according to a study led by a University of Illinois Chicago researcher. From 1980 to 2015, the measurement of inequality grew by 36 percent, compared to 19 percent nationwide.

Hatch remembers when government resources, like public housing, were for middle and working class families and not just the poorest Chicago residents. That helped families like his advance.

“The housing development I grew up in was originally built for Italian immigrants and then Jewish immigrants. “My takeaway is that when European immigrant families needed public housing, public schools, land grants, colleges, FHA loans and so on, we had a government committed to what I call ‘family-friendly public policy.’ We invested in all of those things,” he said.

That all changed as a growing Black Chicago population needed these programs, he said.

Public housing and many other programs became stigmatized and available only to the poorest of Chicago residents.

Today, in Chicago and across the U.S., the rising cost of living means that more middle class families are in need of government financial assistance but don’t qualify for it, sometimes due to narrow income restrictions. Lower-income families face mounting challenges in the pursuit of economic advancement compared to generations that came before them.

While people in the mid-1900s were able to support large families on factory jobs, Calvin Pierce, a Chicago resident who works for a food logistics company at O’Hare International Airport, said his salary isn’t enough to take care of himself.

At $18.65 an hour, just a few dollars above the state minimum wage, he is aware that he couldn’t afford to get seriously sick.

“I’ve never been that sick thankfully. My coverage isn’t that good so I’d really want to wait it out instead of bringing a bill into the house,” he said. “Then we’d have to deal with billing.”

Like so many families in Chicago, he is stuck in that spot where he makes too much to rely on government programs but too little to have financial stability and freedom to pursue goals beyond living paycheck to paycheck.

“I’m not eligible for Medicaid because I make too much but what I’m making isn’t enough.”

Like Pierce, many look to reliable government programs to help them bridge the gap between what they need and can’t afford.

While major changes in the economy over the last century have driven much of the income gap and cost of living in cities like Chicago, policy decisions by federal and local leaders have helped and hurt families as they aim to achieve economic success.

“Economic mobility has become more challenging to achieve for many families. There are so many factors here,” Fernández said. “We can’t just point to one thing.”

Historically, different political regimes have variously expanded and shrunk the social safety net that helped families get ahead. During President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, government programs for struggling families to get health care, education and food expanded with programs like Medicaid, Head Start and food stamps. Decades later, President Ronald Reagan’s cut many of these programs.

Since President Donald Trump won his second election in 2024, he’s prioritized cutting government spending, including financial assistance programs for struggling families.

But Illinois and Chicago lawmakers have their own priorities for addressing the social problems that come out of a rising cost of living.

In this project, we investigate the complicated roots of economic mobility in Chicago and Illinois as well as the successes, failures and limitations of some of the government efforts to solve them.

CREDITS:

Project Editors: Crystal L. Paul, Ruby L. Bailey

Developer and Graphic Design: Cesar Calderon

Contributing Editor: Steve Warmbir

Illustration: Cori Lin/Onibaba Studio

Photography: Akilah Townsend

Engagement: Kayla McLeod & Mumina Mohamud