In 2011, when then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel proposed a budget that closed half of the public mental health clinics in Chicago, City Council passed it unanimously. Less than a decade later, a progressive caucus in the council helped stall the confirmation of Dr. Allison Arwady, Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s choice for commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), citing concerns over her past statements regarding the closures. That sea change in political attitudes was the result of shifting public opinion driven by the tireless efforts of activists, advocates, and mental health providers. But the clinics remain closed, and the battle is far from over.

JFK’s Promise

The modern era of mental health delivery in the United States can be traced to 1963, when President John F. Kennedy passed the Community Mental Health Act (CMHA). The act aimed to reduce the population in the nation’s psychiatric institutions—which offered few opportunities for constructive activities or therapy, let alone recovery—by half, and federal funding incentivized states and municipalities to create a robust system of community mental health agencies. In response, Chicago opened a system of nineteen public mental health centers that spanned nearly the entire city over a fifteen-year period.

Today, five of these public clinics remain. Operated by CDPH, they are financed through a mix of federal, state, and city dollars, in contrast to privately operated community mental health centers, which also sprang up in high numbers after the passage of the CMHA.

The city-run public mental health clinics have always served the city’s most marginalized individuals. Unlike privately operated community mental health centers (even nonprofit ones), city-run clinics have a mandate to serve everyone, including those whom private clinics may turn away for lack of ability to pay or due to the severity of their illness. This makes them a safety net for low-income patients who are not eligible for Medicaid and/or Medicare (including the undocumented). Privately operated mental health centers generally do not gain patient revenue from these individuals, so they have little incentive to accept them as clients.

CDPH representatives often point to Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), which receive federal funding and are also mandated to serve undocumented and uninsured individuals, as an alternative to city-run public mental health clinics. Advocates disagree. “There is a real limit to what [FQHCs] can do,” said Patrick Brosnan, the executive director of the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council. Brosnan said FQHCs have thin financial margins and lack flexibility to provide services that are not reimbursable by Medicaid for free. “In order to get funded, you need to have a diagnosis, you need to have a treatment plan, and those things are important, but it’s not necessarily the kind of services that everybody needs.”

Dr. Arturo Carrillo, who leads the Collaborative for Community Wellness (CCW), said that FQHCs are limited when it comes to serving individuals with severe mental illness and long-standing trauma. “When they say trauma, what we’re talking about is years, decades, of accumulated sense of loss, harm, and exploitation, and this is an issue that is more pronounced in low-income communities,” Carrillo said. FQHCs are set up to offer short-term treatment relative to the city-run public mental health clinics, which do not have limits on the number of sessions one can attend, he explained, but establishing trust and safety with patients—who are often dealing with complex trauma—takes time. The public clinic model “is set up to be a resource for communities where people can have a continuing relationship with a therapist,” he said. “FQHCs are about churning through patients.”

After the CMHA was passed in 1963, states, taking advantage of federal incentives and funding shifts, moved away from operating psychiatric institutions in favor of community-based care settings. At the same time, Medicaid and Medicare were created; Medicaid became the single largest funder of mental health services in the United States. As a result, today’s state mental health agencies rarely have direct responsibility for patient care, instead contracting services out to a variety of private entities, both for-profit and nonprofit, privately and publicly operated. According to one 2006 analysis by health economists at Harvard and Columbia Universities, this fragmentation of public responsibility in caring for people with mental illness has reduced patients’ overall wellbeing.

An Austerity Era

Kennedy’s plan called for gradually replacing initial federal incentives with local (state and city) investment, but these funds were rarely, if ever, appropriated to sustain the system of community-based mental health centers that had been established from the CMHA. This left both public and privately operated community mental health centers reliant on meager state mental health agency budgets and shrinking federal dollars. Making matters worse, in 1981, then-President Ronald Reagan shifted states’ fiscal responsibility for community mental health services (both public and private) to shrinking federal block grants. What followed were cuts in state mental health agency budgets that occurred almost annually. State mental health agencies coped with cuts by reducing staff and services and closing state hospitals.

The switch to block grants didn’t just reduce the money available for mental health services—it also changed how it was distributed. To compensate for the annual funding decreases associated with block grants, states have shifted their mental health agency budgets to take advantage of Medicaid’s federal matching program, which decreases states’ financial responsibility for Medicaid-eligible individuals from a hundred percent to only seventeen-to-fifty percent of costs. While this budget shift increases the overall funding for Medicaid-eligible clients with mental illnesses, it reduces funds for services to non-Medicaid eligible clients—the primary population served by Chicago’s city-run public mental health clinics.

Currently, the majority of funding for the city-run public mental health clinics in Chicago comes from Community Development Block Grants, a federal-level Housing and Urban Development (HUD) initiative. The value of those grants has decreased seventy-four percent in inflation-adjusted dollars since their inception.

Chicago’s network of publicly funded and operated mental health clinics has contradicted aspects of national funding trends—but this has made them vulnerable to neoliberal political whims. Richard M. Daley closed seven of the city’s original nineteen public clinics in the 1990s despite significant community backlash. The remaining twelve clinics were not unaffected; budget cuts forced them to cut staff and reduce services. In 2009, Daley, citing a $1.2 million reduction in state funding (which Springfield blamed on billing errors during the state’s transition to a fee-for-services system), floated the idea of closing still more clinics.

Daley never followed through, but when Emanuel took office in 2011, his first budget included closing half of the twelve clinics that remained—and the city council passed it unanimously. Reader columnist Ben Joravsky suggested that one explanation for aldermen’s acquiescence was that the budget vote coincided with the redrawing of ward maps—leading even the most progressive of aldermen to vote more out of deference to the mayor than commitment to their constituents’ interests. The impact, however, was evident. Four of the shuttered clinics were on the South and Southwest Sides. One of those was one of only two that offered bilingual services in Spanish and English.

Emanuel’s justification for the closures? Savings of roughly $3 million, or 0.04 percent of the city’s $8.2 billion budget. The administration also argued that the Affordable Care Act and expansions to Medicaid would extend insurance coverage and reduce the need for public clinics.

In 2016, another city-run clinic on the Far South Side was transferred to private management, leaving Chicago with only five publicly funded and operated mental health clinics—a quarter of what the city started with in the 1970s.

Communities Fight Back

In the wake of pressures to shrink and privatize the mental health system, communities have responded in many ways. In the 1990s, a group of community advocates formed the Coalition to Save Our Mental Health Centers, which resisted clinic closures through the early 2000s. After Daley closed seven clinics, the Coalition refused to lose faith, but did switch tactics. In 2004, they turned their energy to organizing the Expanded Mental Health Services Program (EMHSP), which created an innovative model to finance and operate community-based mental health centers. Under the EMHSP, communities can place a referendum on their local ballot asking residents to vote on an increase in property taxes (approximately an extra $4 for every $1,000 paid in property taxes per year) to fund local mental health services. Communities can initiate, approve, and fund new mental health centers themselves.

Bypassing the city to focus on statewide reform, the Coalition led efforts that resulted in passing the Community Expanded Mental Health Services Act in 2011, which allows any community in Chicago to create an EMHSP. To date, three communities have passed an EMHSP referendum, each with over seventy-four percent of the community voting in favor—a wide margin of approval indicating that Chicago communities are committed to helping finance community-based mental health treatment.

At the same time that the Coalition to Save Our Mental Health Centers was working to create and pass a new funding stream for mental health services in Chicago, another group of advocates pressured the city to strengthen the city-run public mental health clinics. When threats of clinic closures began again in 2009, the Mental Health Movement (MHM), an initiative within the activist group Southside Together Organizing for Power (STOP), led a campaign of demonstrations against the closures. The MHM is composed primarily of individuals with lived experience of mental illness and consumers of mental health services.

Upon hearing the news of the Emanuel-mandated clinic closings, the MHM acted quickly. On the day the Woodlawn clinic was slated to close, the group staged a protest in which more than twenty people were arrested. STOP activists chained themselves to the clinic, in some places three people deep. “It was hours before police were able to make it through a side door and arrest everyone,” said Amika Tendaji, STOP’s lead MHM organizer. “Those cases for the people who got arrested lasted way longer than they should have. It was a demonstration of Rahm’s cruelty.” Shortly after the protest, the Woodlawn clinic was permanently closed.

In 2016, without any public input or hearings, the city announced its plans to privatize the Roseland clinic, one of the six city-run public mental health clinics remaining. On a cold day in December of that year, MHM activists occupied the clinic. Ronald “Kowboy” Jackson, a MHM leader, chained himself to the clinic doors for hours until police forcibly removed him. Soon after, the Roseland clinic was privatized, displacing mental health providers and patients alike.

Tendaji said the impacts of displacement due to privatization were profound, causing disruptions in longstanding patient-provider clinical relationships. “It wasn’t just a switch in therapist,” she said. “This was their entire clinical environment.” Part of what inspired the resistance to clinic closures was a real fear among patients that they would lose therapists they had worked with for years, she explained.

Meg Lewis, director of special projects at AFSCME, the union that represents the public mental health clinic employees, says that even as therapists dealt with layoffs due to closures, they were concerned about how their clients would be impacted. “They really did not want to see people fall through the cracks,” Lewis said. “These are safety net services, and it was very unclear at that point if the city had a plan for continuity of care for people who were receiving services at the clinics.”

A Healing Village Grows

Following the closures, advocates knew they had to switch tactics once again. In 2018, in an effort to create a catalyst for mental health organizing that went beyond the issue of the clinic closures, the MHM created the Healing Village. By using an imaginative place-based organizing venue at 61st Street and Greenwood Avenue in Woodlawn, MHM advocates aimed to “challenge what mental health could be, looking at community building as an aspect of healing,” Tendaji said.

The group partnered with Project Fielding, an organization that trains women and gender nonconforming individuals in carpentry. Project Fielding volunteers had built two structures intended to go to Dakota Access Pipeline protesters at Standing Rock. The buildings never made it, but went to Healing Village instead. The first vacant lot organizers chose for the Village belonged to corrupt Woodlawn property owner, longtime neighborhood power player, and pastorLeon Finney Jr. He complained to then-20th Ward Alderman Willie Cochran, who had initially given organizers permission to use the lot, according to the Reader. The alderman told the activists to move, so they packed up the structures and set up at 61st and Greenwood instead.

After organizers moved, Cochran drove by to tell them in person that he still did not like the space they had built. Cochran (who was under federal indictment at the time, and is now serving a year in prison for accepting bribes and misusing campaign funds) put a cease-construction order on the lot and told organizers that a bulldozer would be coming. MHM organizers stayed overnight to ensure the space would not be bulldozed.

Healing Village came at a critical time for the community: the day after its launch, members of the South Shore community were attacked and beaten by Chicago police officers during a protest of the CPD’s murder of a local resident named Harith “Snoop” Augustus. Although the Village had planned to hold a barbecue and game day for its first event, it instead became a place where community members could decompress from the protest. The Village was filled with tears while community members held and comforted one other. A parent whose son had also been murdered by police delivered a powerful speech. “In ways that are difficult to describe, there was something more powerfully healing about being outside, being in the sun, being together with your community in that space,” Tendaji said.

Throughout that summer, community members—including those with and without mental health issues—came to the Healing Village for art therapy workshops, to tend to the garden, and to play games. Various organizations hosted resource fairs and facilitated intentional community building in the space. According to Tendaji, two mothers who lived adjacent to the block and had lost children to gun violence met for the first time at the Healing Village. Butterflies, a symbol the MHM adopted years prior, were prominent at the Healing Village, where they were attracted to the garden and a nearby field brimming with clover.

As fall arrived, and with it the first signs of another Chicago winter, organizers and community members disassembled the Healing Village. It had succeeded in educating community members about the lack of affordable services in their neighborhoods and the importance of public, rather than privatized, mental health clinics.

Backing Direct Action with Data

On the West Side, Saint Anthony Hospital’s Community Wellness Program (CWP), which offers mental health services, had also noticed a gap in mental health providers in the neighborhoods they served once the clinics closed. The CWP, which serves primarily Spanish-speaking individuals without insurance, saw that between 2012 and 2016, waitlists and referrals for individuals seeking services had nearly doubled. And after Donald Trump’s election in 2016, calls requesting appointments for mental health services at the CWP reached an all-time high. Recognizing that their program was unable to meet the needs of the communities they served, in 2016 the CWP convened the Collaborative for Community Wellness (CCW).

The CCW is a coalition of people with lived experience of mental health concerns, mental health service providers, and community-based organizations, including STOP, Pilsen Alliance, and Brighton Park Neighborhood Council. As a first step in their organizing campaign, CCW assessed mental health needs for individuals in ten high-poverty, primarily Latinx and African-American neighborhoods on the Southwest side of Chicago.

The CCW’s research found that, contrary to a popular public narrative, it is not stigma or lack of interest that stops community residents from seeking mental health services, but inability structural obstacles that stand in the way of easy access. More than eighty percent of the approximately 2,850 individuals surveyed said they would seek professional help for personal problems, but reported barriers to service that included high costs, long waitlists, and lack of transportation or childcare.

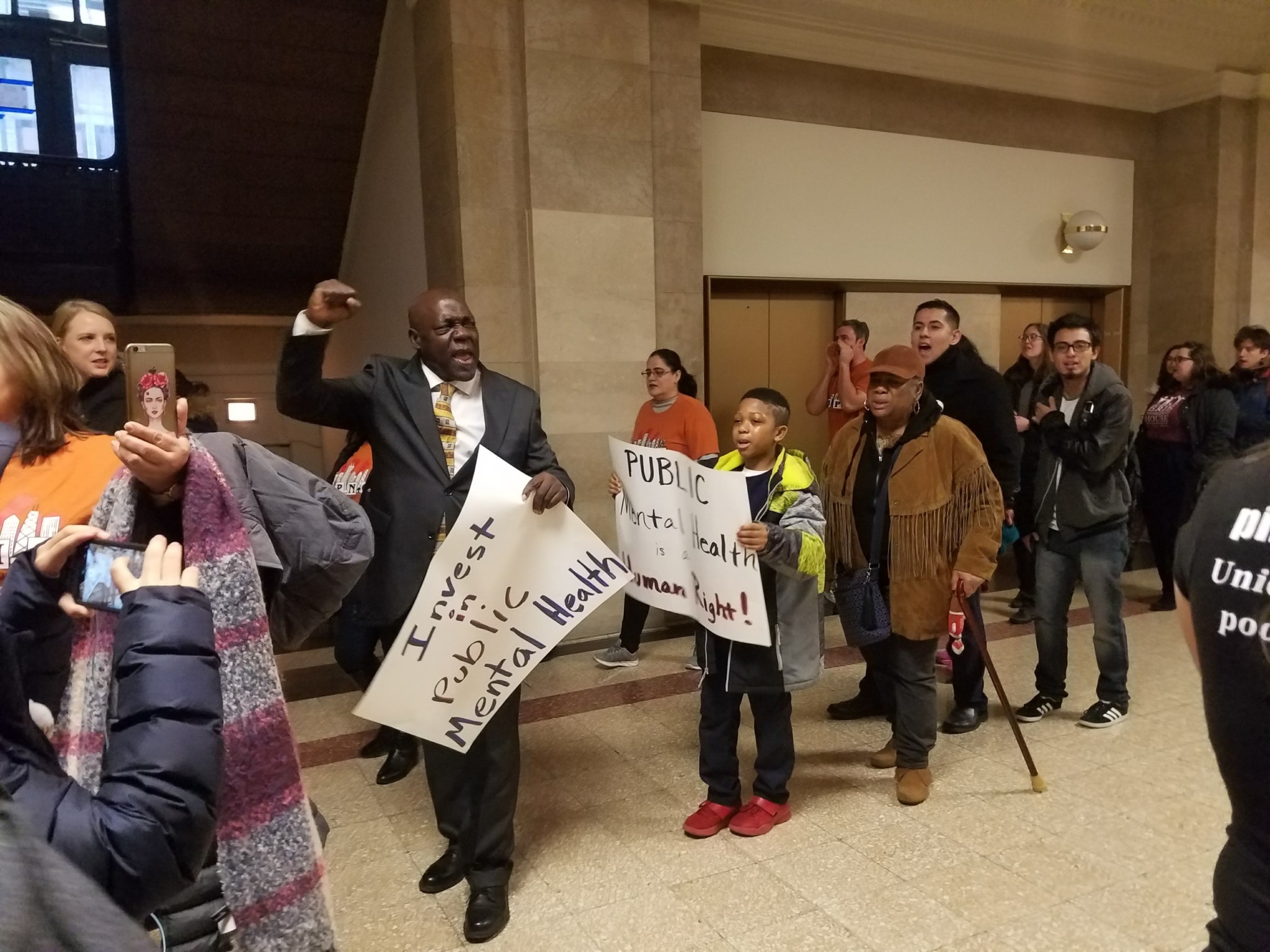

With clear data showing there is a high need and desire for mental health services, especially in low-income Black and Latinx neighborhoods, the CCW began its advocacy campaign to pressure the city to reopen the closed clinics. In the fall of 2018, the MHM joined the CCW to protest and rally at the site of a closed public mental health clinic in Back of the Yards. In November, responding to pressure from CCW members who were constituents, then-22nd Ward Alderman Ricardo Muñoz introduced a $25 million amendment for public mental health services. But the amendment was not included in the final budget, a signal to organizers that they needed to switch tactics and collect more city-wide data.

In 2018, Dr. Judy King, a key mental health advocate in Chicago and member of the Chicago Mental Health Board, used a FOIA request to obtain the CDPH’s list of 253 mental health service providers. Using King’s list, CCW members conducted a systematic assessment of the accessibility of the city’s mental health providers. They identified many barriers to access, most fundamentally an inability to contact providers: CCW researchers placed at least two phone calls to each organization, and approximately forty percent of listed providers (103 agencies) could not be reached, were duplicate listings, or had ceased to function. Other issues—long waitlists for services, a dearth of facilities offering services in Spanish, and limited free services for low-income individuals—overlapped with the findings of the earlier, ten-neighborhood survey. Furthermore, the data revealed spatial inequities in the distribution of mental health providers, with a markedly lower number of accessible providers on the city’s South and West Sides.

Organizing Gets the Goods

In January 2019, a ray of hope emerged for advocates who wished to move beyond simply protesting against closures to strengthening and growing the city’s public mental health system. The CCW and MHM partnered with AFSCME to lobby 4th Ward Alderman Sophia King, who helped advocates create and pass a resolution that established the Public Mental Health Clinic Service Expansion Task Force. The task force was directed to explore the possibility of reopening public mental health clinics.

At the Health and Human Services Committee’s hearing on the resolution, CCW advocates handed out their report assessing CDPH’s list of mental health providers for real-world accessibility. 35th Ward Alderman Carlos Ramirez Rosa cited the CCW’s research in his testimony supporting the passage of the resolution. Dr. Carrillo said the research “pushed a different discourse in the conversation that wouldn’t have been there if it were not for the work of the collaborative.” Additionally, CCW and MHM members provided key testimony during the committee hearing, and a strong community presence maintained public pressure to advocate for its passage. The measure passed unanimously through City Council, despite opposition from Dr. Julie Morita, then the city’s public health commissioner.

The resolution also mandated the task force hold a public hearing to assess the impact of the public mental health clinic closures and garner suggestions from community members on how to improve Chicago’s mental health system. The hearing was held in June 2019 at Malcolm X College with more than two hundred residents from across the city attending. For more than two hours, community residents shared oral and written testimony about how the closures severely limited their options for accessing mental health services and recovering from their mental illness. Researchers partnered with the CCW compiled the testimony into a report that was made public and shared with elected officials.

The public hearing and release of the report further increased pressure for aldermen to support public mental health services. In October 2019, aldermen in the Health and Human Services Committee, led by members of the Progressive Reform Caucus, took the highly unusual step of stalling the confirmation of Lightfoot’s nominee for Public Health Commissioner, Dr. Allison Arwady, because she had previously defended the public clinic closures in formal testimony. Arwady was later confirmed in January 2020, but only after Lightfoot, facing mounting public pressure to fulfill a campaign promise she made to reopen the clinics, made concessions that included an additional $9.3 million in mental health. Budget negotiations culminated in an increase of funding to upgrade the existing public mental health clinics, increase support staff, and fill clinical vacancies while prioritizing the hiring of bilingual staff. But Lightfoot’s first budget—which City Council passed—failed to reopen a single clinic.

Still, significant legislative progress has been made not only to protect the remaining city-run public mental health clinics but also to increase city funding and commitment for mental health services in Chicago. This likely would not have occurred without the public pressure mobilized by grassroots activists and bolstered with community-led research.

“Mental health is an approach to increase unity within our fractured communities, which have experienced violence,” Dr. Carrillo said. “If every community in the city had a community wellness program, a resource center in which people could walk in and get mental health support and a variety of family support, in a way that’s free and accessible, we would have a different city.” Though mental health clinics remained shuttered across the city, advocates will continue to push for a mental health system where high-quality and effective treatments are available to all Chicagoans, not just to those in high-income neighborhoods with private insurance.

Public mental health clinics are “the cornerstone of the mental health system, of the city’s safety net,” said Lewis. “In the same way that we need public schools and public libraries, we need a public health system. There’s other organizations that are doing great work, but ultimately we want to make sure that folks have free care, walk-in care, care in the neighborhoods where they need it.”

Dani Adams is a PhD student at the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. She lives in Pilsen and is a member of the Collaborative for Community Wellness, one of the coalitions discussed in this piece. She helped with the Collaborative’s most recent reports cited in this article, including the report assessing CDPH’s mental health provider list for real-world accessibility, and the report from public hearing testimony. This is her first contribution to the Weekly.