August 13 marks the 500-year anniversary of the Fall of Tenochtitlan—modern-day Mexico City. Through a virtual and printed map and a series of free community events, the project Chicagotlan: Finding Tenochtitlan in Chicago invites Latinx, Indigenous, and Mexican-American youth, and all Chicagoans, to contemplate and commemorate the catastrophic and world-changing event that led to the rise of a historical system that shaped and continues to shape political, economic, and social relations across the globe.

Spanish colonizers, driven by an imperialistic lust for gold and land and an obsession to proselytize the Indigenous, had successfully taken advantage of divisions among the Valley of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples and made an alliance with the Tlaxcalans—the rivals of the Mexica, commonly known as the Aztecs. Bolstered by tens of thousands of Tlaxcalan soldiers, the Spanish waged a three-month siege against Tenochtitlan.

Outnumbered, and with his people starving and beleaguered by a tool of biological warfare—a smallpox epidemic—Cuauhtémoc surrendered to the Spanish on August 13, 1521. He was only twenty-five years old and had just emerged as Tlatoani (ruler) of the Mexicas after Cuitláhuac, Montezuma II’s successor, had himself succumbed to smallpox. Montezuma II, Aztec emperor at the time of the Spanish arrival, had died thirteen months earlier during a Mexica insurrection against the Spanish colonizers, according to historians.

Tenochtitlan was two times the size of Paris, Europe’s largest city in the sixteenth century. In the immediate aftermath of the conquest, the Fall of Tenochtitlan resulted in the tragic killing and capture of an estimated forty thousand Indigenous civilians. It is reported that thousands of bodies floated in the city’s canals. The great city of Tenochtitlan, which was once home to between 200,000 and 400,000 inhabitants, now lay in ruins.

The conquest led to the ongoing occupation of Indigenous territory for the next 500 years. It led to the genocide of Mesoamerica’s Indigenous peoples at the hands of the Spanish Empire and the Catholic Church. The Fall also shaped the contemporary Mexican nation and the present-day metropolis of Mexico City, as well as paved the way for Spanish expeditions into what is now the United States, Central America, and South America.

While the Spanish laid siege to Tenochtitlan in an attempt to eradicate Indigenous peoples, Indigenous knowledge systems, and Indigenous cosmologies, Indigenous peoples survived the conquest and continue to survive the ongoing legacy of colonialism.

Tenochtitlan continues to exist not just in Mexico City, the new capital literally built atop the ruins, but also here, in the capital of the Midwest. In metropolitan Chicago, 1.1 million people of Mexican descent comprise seventy-five percent of the area’s Latinx population. As we approach the 500-year anniversary of the Fall of Tenochtitlan, we can examine the ways in which Tenochtitlan is alive in Chicago and other cities. We can ask: How does Tenochtitlan appear in our public murals, community spaces, and local institutions?

Chicagotlan: Finding Tenochtitlan in Chicago was conceived in the summer of 2021 by the Chicagotlan Organizing Committee members, who were born in the U.S. or Mexico, and raised in Chicago. Chicagotlan was created out of a desire to commemorate and historicize the Fall of Tenochtitlan and the legacy of colonialism, while educating and creating dialogue with younger generations of Mexican-American and Chicanx Chicagoans about their history and the cultural and educational resources available in their backyard.

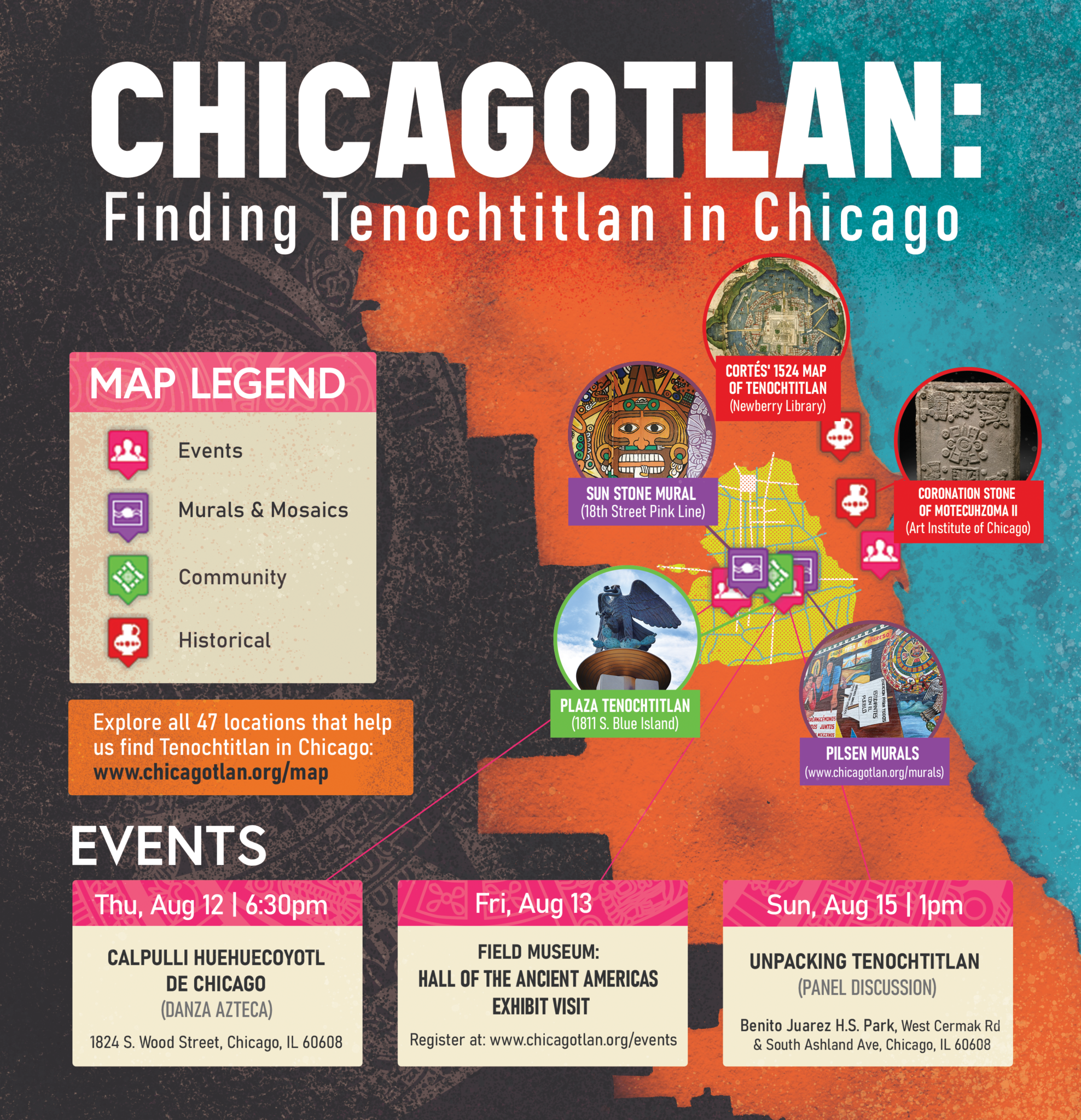

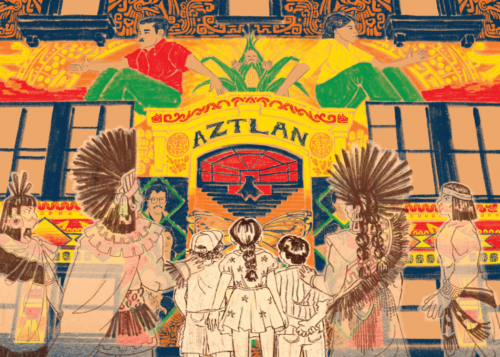

Chicagotlan’s full virtual map, found at chicagotlan.org/map, invites participants to visit well-known community spaces: Pilsen’s Plaza Tenochtitlan, the 18th Street Pink Line Stop, the former Casa Aztlan community center, the Aztec-inspired mural outside Benny’s Pizza #2, and many other sites on an evolving and growing list.

The map also invites participants to visit lesser-known locations, such as the statue of Cuauhtémoc outside of Benito Juarez Community Academy, the fifteen-foot statue of Mexico’s first Indigenous president off Michigan Avenue, the 1503 Coronation Stone of Motecuhzoma II at the Art Institute of Chicago, colonizer Hernán Cortés’s 1524 map of Tenochtitlan at the Newberry Library, the hundred-foot-tall Native American pyramid at the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, and the lesser-known mounds at Kincaid Mounds State Historic Site.

In total, the online map highlights forty-seven community spaces, local institutions, archeological sites, and historical and/or sacred objects that have been politically, economically, socially, intellectually, and spiritually formative for migrants that originated or traveled through what is now known as Mexico and settled in Chicago.

The map is an ongoing project that locates the ways in which Tenochtitlan and Chicago speak to each other across time and space. Chicagotlan’s map is not meant to be an exhaustive list, but an invitation to contextualize the Fall of Tenochtitlan, the links between Chicago and the Mexica capital, and the ongoing project of colonization of the Americas.

Chicagotlan asks the question: What are the histories that link the geographies of Chicago and Tenochtitlan? For example, how did Montezuma II’s coronation stone, undoubtedly sacred and a piece of the living history of the Valley of Mexico’s original peoples, end up in a Chicago museum? The Art Institute’s website indicates that they purchased it from the Time Museum in Rockford, Illinois in 1990, which acquired it from a private gallery in Los Angeles in 1971. How did the coronation stone end up in Los Angeles in 1971?

It also invites participants to contemplate the ways in which the original peoples of the Americas and their descendants have resisted colonization. To this end, we highlight the First Nations Garden in Albany Park, created by the Chi-Nations Youth Council on publicly owned land in the spring of 2019. The garden, whose fence is decorated with a number of murals that draw on Mexica symbols and iconography, represents Indigenous-led resistance to colonization and a furtherance of the Indigenous demands of the Land Back movement.

By exploring Chicago’s existing resources, Chicagoans can gain a better understanding of history and the Aztec capital’s enduring legacy.

Chicagotlan: Finding Tenochtitlan in Chicago events take place Thursday, August 12, Friday, August 13, and Sunday, August 15, and are free and open to the public. For more information and to register (required) for the August 13 event visit chicagotlan.org.

Carlos Ramirez-Rosa is alderman of the 35th Ward. Ismael Cuevas Jr. has an M.A. in Mexican American and Latina/o Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. Both are members of Chicagotlan’s organizing committee and both have previously contributed to the Weekly.