On July 1, the Hyde Park Academy local school council (LSC) voted to remove one of the school’s two school resource officers (SROs)—Chicago police officers assigned to individual public schools—and reinvest the funds into a dean of climate and culture position. The decision comes a year after a historic summer of students fighting to get police out of Chicago Public Schools (CPS).

As students return to Hyde Park Academy High School this fall, they will find one less SRO and in place of them, an administrator whose role is devoted to restorative justice. A year ago, some deemed it impossible to remove SROs from Hyde Park Academy—last summer, the LSC voted 9-0 to keep both SROs. But now, those who advocated for removing them entirely are halfway to achieving that goal. What changed?

In April, CPS Chief of Safety and Security Jadine Chou announced that SROs would not return to CPS high schools for the remainder of the school year. Additionally, the remaining fifty-five high schools that opted to keep SROs last summer were instructed by CPS to establish a whole-school safety plan, which would be created by each school’s safety committee. The committees would then present the plan to the LSCs by July 14.

In the case of Hyde Park Academy, the safety committee, which was made of school administrators and staff, including the school’s three-person counseling team, a student, a young alumnus, a community member and members of the LSC, recommended whether the school should keep both, one or zero SROs.

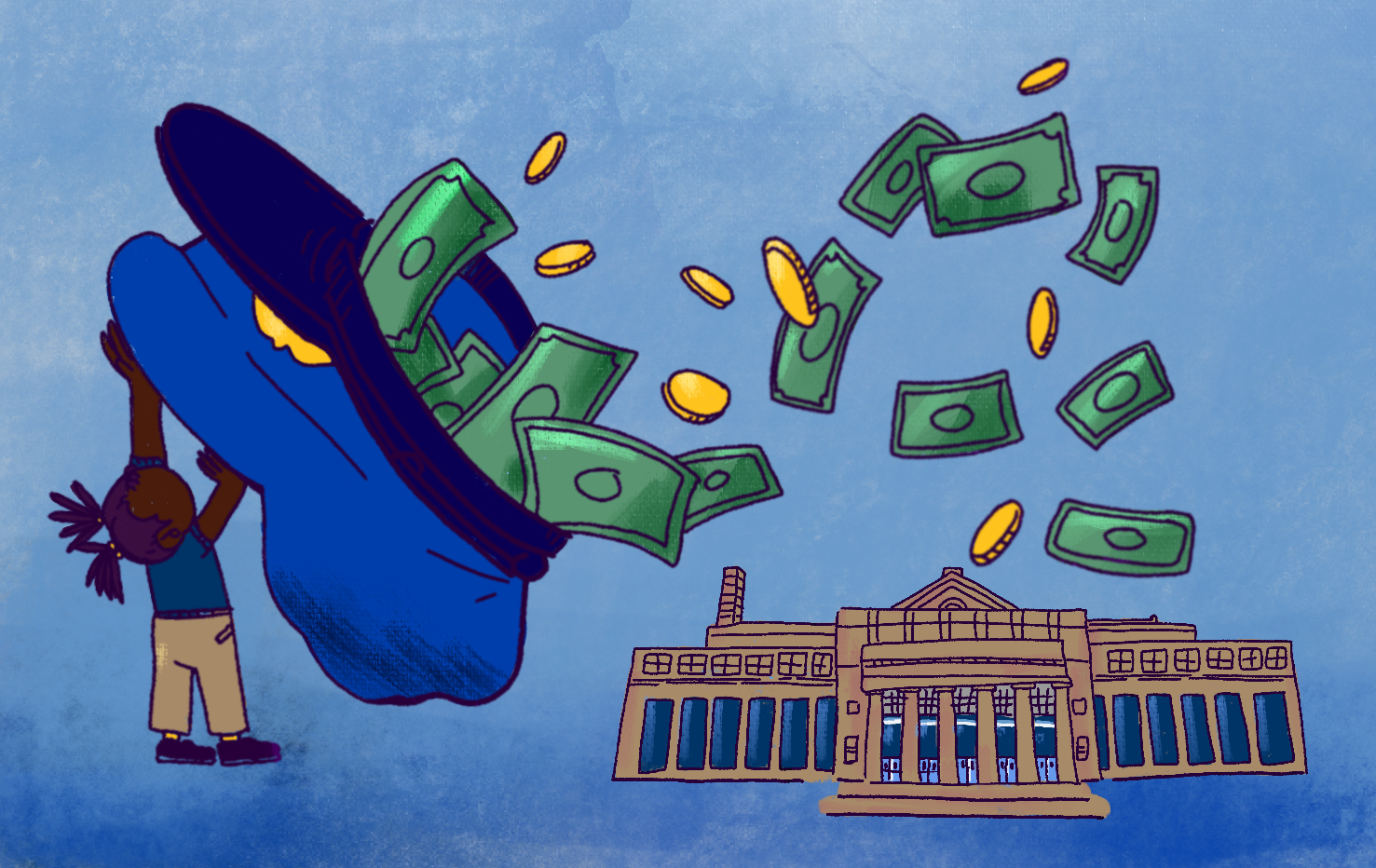

The LSCs were also informed that with every SRO that the schools chose to cut, they would receive funds to go towards holistic services and alternatives to policing, said Maira Khwaja, a community member on the Hyde Park Academy LSC. Schools will receive anywhere from $50,000 to $75,000 per SRO removed, a number which fluctuates by school depending on the CPS equity index, a new tool to “help identify opportunity differences so that resources can be prioritized for the schools in greatest need” which was informed by community feedback, according to the CPS website.

At Hyde Park Academy, these funds will go toward a dean of culture and climate, a high-level administrative position that will manage conflict resolution, restorative justice and a peace room, things which other schools have already adopted.

“Hyde Park has made some effort towards adopting it but truthfully, they don’t have the capacity,” Khwaja said. “There’s nobody that is specifically looking to be in touch with every single student and lead conflict resolution efforts in a way that does not necessarily feel punitive.”

Other CPS high schools, including Roberto Clemente Community Academy, Lincoln Park High School and W.H. Taft High School have already implemented deans of culture and climate or similar positions.

The dean of culture and climate will be different from other administrative roles and will be a polar opposite to the role of SRO. According to Khwaja, where the SROs at Hyde Park Academy are supposed to distance themselves from students and have a clear power dynamic as a person who has the authority to arrest students, the dean is meant to be in constant contact with students and work to remove toxic power dynamics.

“What we would be looking for is not somebody who, as soon as they enter the room, the power imbalance feels very threatening,” Khwaja said. “That makes it very hard to actually mediate any type of conflict, that’s just using a hammer to say we cannot discuss this conflict, the power dynamic’s clear this is over. We don’t want to shut down students in that way with this person that would be coming in.”

Climate and culture positions look different at every school, depending on what administrations are looking for and the student populations’ needs.

Kat Hindmand is director of climate and culture at Taft High School. Before starting the position seven years ago, Hindmand worked at the CPS central office where she oversaw the safety and security of all North Side schools (about 150) and at one point all North and West Side schools (about 300). She is also a licensed clinical social worker.

At Taft, which has a student population of around 4,000 spread across two campuses, the job isn’t small. Hindmand’s position includes managing all student discipline and behavioral supports, which includes mental health. She is also in charge of all emergency drills and the crisis team and works closely with the security team, which includes the school’s two SROs.

The goal of Hindmand’s position? To drastically alter the school’s environment around discipline. “It’s really about changing the culture, from one of punishment as a way to deal with kids to using restorative practices to help them learn from their mistakes. So that they don’t keep repeating them,” Hindmand said.

One part of managing behavioral supports includes working with Taft’s behavioral health team of social workers, school counselors and climate and culture administrators, which meets every week to address student’s behavior, mental and emotional health needs. If a student requires resources that cannot be met by a school counselor or social worker, they’re provided outside service, which is billed to students’ medical insurance or Medicaid, by clinicians from Lutheran Social Services who come into the school to meet with students.

While Taft has been able to make strides in the school culture, have other schools been able to do the same? According to Hindmand, CPS is working to shift the district’s overall culture from one of punishment to restorative justice.

While there were only a handful of climate and culture positions when Hindmand began in 2014, there has since been an increase in positions. As of March 2021, out of over 42,000 CPS employees, there were 80 who held job titles pertaining to climate and culture, fifteen conflict resolution specialists and 763 school counselors—some of the primary roles that make up a school’s behavioral health team.

Schools are funded by CPS based on student population. Therefore, the more students, the higher the funds. At a school as large as Taft, they are able to hire more climate and culture positions than others and when there aren’t sufficient funds for the positions necessary to meet students’ needs, Hindmand will seek outside support.

At Hyde Park Academy, where the student population is around 700, there is less funding to hire climate and culture positions.

The change that provided Hyde Park Academy with the funds to create the new position cannot simply be chalked up to CPS suddenly choosing to provide high schools with options and resources for them to define safety on their own. Student organizers applied the pressure and changed the narrative.

Davione Jackson is a rising junior at Hyde Park Academy and an organizer with Southside Together Organizing for Power (STOP). He is also on the school’s safety committee.

He said he Khwaja’s words on power dynamics resonate with him. While he’s happy about the removal of one SRO, he won’t be satisfied until both are removed, their presence replaced with people and programs who can support students.

“I feel that it’s best to have more social workers or something for the students to be able to talk to because students go through a lot, even though it might not show and that’s one of the reasons or causes for different altercations at school,” Jackson said. “We don’t really have people to go to since there’s not really a lot of counselors and the counselors that we do have, we have to share with all grades.”

Students and their allies have protested, called, emailed, organized and even showed up at the door of school board members’ homes to fight for the removal of police from schools. The steps that CPS is taking to, in part, comply with students’ demands is proof of the ground that has been gained. But organizers aren’t satisfied.

In a statement released on July 2, announcing the removal of the SRO, Executive Director of STOP, Alex Goldenberg, wrote that while this was considered a victory, the coalition of organizations and individuals who have fought to remove SROs from Hyde Park Academy are only getting started.

“We are not sitting down and we are not taking a break. We will not stop until all police are removed from our schools,” Goldenberg said. “We will work to build alternatives to policing in our school.

“Last year, our school—and nearly all majority Black schools—voted unanimously to keep the police in the school. They said it was impossible for a majority-Black school on the South Side to remove police…well, Black students made the impossible possible. Now let’s get back to work and finish the job.”

Grace Del Vecchio is a Philadelphia-born, Chicago-based freelance journalist primarily covering movements and policing. She is a former City Bureau fellow and the current editor-in-chief at DePaul University’s student-led publication 14 East Magazine. This is her first piece for the Weekly.

About “Paving the Road from Punishment to Restorative Justice in CPS,” it is painful to see how slowly CPS is moving to give students a meaningful role. When trouble is coming, who knows it first? Students. Who can intervene earliest to calm things down? Students. Properly trained & motivated, they can gain peer trust earlier and douse sparks in peace circles before they become conflagrations.

This process should start in 6th – 8th grade, not high school. It can work when administrators allow it to work. Yes, even in black communities. I have been involved as a volunteer in such projects at South Side schools for years.

Although Hyde Park is moving in the right direction, based on your article, it still sounds like a system imposed and run “from the top down.” Real change comes when students have some ownership and input.