In 1971, civil rights lawyer Anna Langford became the first Black woman to serve in Chicago’s City Council. An independent, she was elected to represent the 16th Ward, which at the time encompassed much of Englewood, roughly spanning from Stewart over to Ashland, and Garfield down to Marquette. Langford frequently clashed with Mayor Richard J. Daley and became known as a thorn in the side of the machine.

Growing up in Englewood, Sonya Harper—a longtime neighborhood organizer who now represents parts of Englewood and surrounding areas in the Illinois House—said she learned from her elders that Englewood was gerrymandered into multiple wards as a challenge to Langford’s power.

There’s no definite proof that the political fragmentation of Englewood was intended as a punishment for Langford. But Daley was known for redrawing wards to take power from independents who challenged him, and it is true for that for a variety of reasons—covered in the previous installment of this series—the ward once governed by Langford is now split into five oddly-shaped wards. The 6th, 15th, 16th, 17th, and 20th Wards all have small pieces of Englewood and West Englewood (the 3rd Ward also takes a tiny corner). And the very endurance of the Langford story shows that the neighborhood’s gerrymandering has long weighed heavily on its residents’ minds.

“Ever since I got into organizing and working in the community, one of our biggest challenges that we’ve always had is knowing whenever we want to get something done, we have to consult five or six different people,” Harper said. “When people look at the Englewood community and all the challenges that we deal with and how we’re portrayed on the news media, the one thing that they don’t know is that we’re split up politically and that lends itself to some of the dysfunction that we have. Englewood gets such a bad rap but I believe that that is one of the biggest reasons why.”

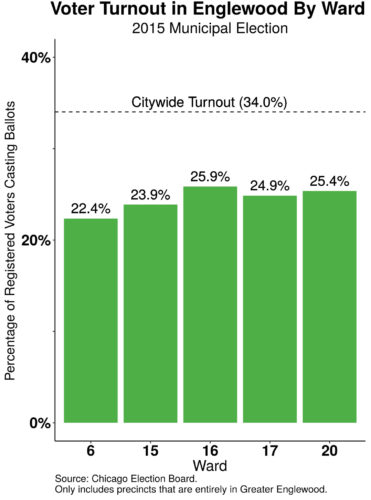

Combined, the population of the Englewood and West Englewood community areas is 56,818, according to 2016 Census data. That’s roughly the size of a Chicago ward, which, in the last remap, were drawn to range from roughly 51,000–56,000. But while other communities—like Bridgeport—are largely concentrated in one ward with one elected official to lobby, Englewood’s voting power is split. In 2012, Harper helped organize an Englewood Votes campaign to educate voters about their elected officials and try to increase voter turnout, with the hope that better turnout in the Englewood portions of wards would result in better attention from elected officials. The group registered 400 voters for the 2012 presidential elections, and hosted aldermanic forums in 2015. But Englewood’s struggles with voter turnout have continued—precincts within Greater Englewood had a total turnout of 24.6 percent in the February mayoral elections in 2015, much lower than the citywide thirty-four percent.

Englewood has a variety of community groups that organize on the neighborhood level: Resident Association of Greater Englewood (RAGE), Imagine Englewood If, Teamwork Englewood, and many more. But implementing neighborhood-wide projects can require getting as many as five aldermen at the same table to agree on a plan. It “definitely” makes the job harder for Asiaha Butler, the co-founder and director of RAGE. “The current status of our community has a lot to do with our political division,” she said in an interview. “It doesn’t make [my job] impossible, but it does make it more challenging.”

Harper formerly directed Grow Greater Englewood, a nonprofit that aims to support community-based agriculture and food businesses. Recently, she said, Grow Greater Englewood has hit a snag while attempting to get aldermanic approval to place more urban farmers on land in the urban agriculture district, which runs across the planned Englewood Line rail-to-trail project on 59th Street. The proposed Englewood Line runs from Halsted to Damen—crossing through the 15th, 16th, and 20th Wards—and the aldermen haven’t always agreed on whether to approve the group’s plans.

“All the aldermen aren’t talking together,” said Anton Seals Jr., Grow Greater Englewood’s current director. “I think for many of the community groups it puts pressure on us to organize across the neighborhood. It kind of stalls the project when we don’t have everyone on the same note or even sometimes in the same book.”

Toni Foulkes, who has represented much of Englewood as first the 15th and now 16th Ward alderman since 2007, said that the project has been delayed partially due to disagreement among the neighborhood’s aldermen, because 15th Ward Alderman Raymond Lopez had a different idea, involving building a loop in the trail up to 47th Street. Foulkes said in a phone interview that Lopez’s idea will “never manifest,” and added that now all the relevant aldermen are in support of the project as proposed—“There’s nobody pulling against it.”

There is perhaps no better recent example of the ways in which political fragmentation has hurt and displaced residents of Englewood than the expansion of the Norfolk Southern rail yard. In 2013, City Council approved the shipping company’s long-gestating plan to expand its 47th Street rail yard eighty acres south, into a residential corner of Englewood. The outgoing alderman, Willie Cochran—currently serving out the rest of his term under federal bribery charges—supports the project, and has received thousands in donations from Norfolk Southern since its approval. In the recently-released documentary The Area, current and former residents strongly criticized Cochran for being nearly invisible on the issue. Foulkes attended a community meeting about the expansion when she was still 15th Ward alderman, “and I was the only alderman there,” she said in an interview. “The only thing I could tell [residents], unfortunately, was that the alderman they needed to talk to, they’re not here.” Butler said she didn’t think the project would have gone forward with a less fragmented ward map.

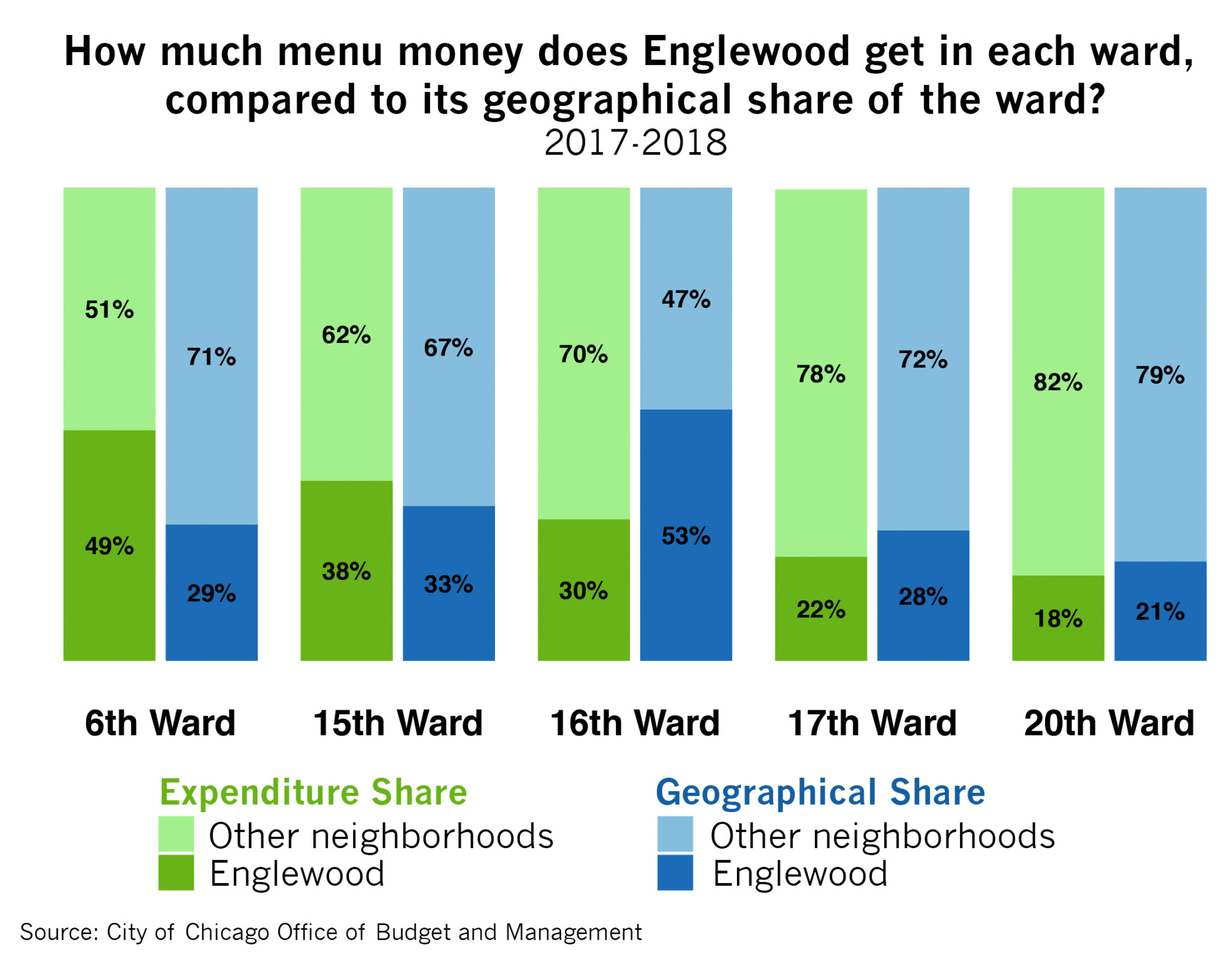

Some residents feel that because most of the wards have power bases outside of Englewood, the neighborhood sees less financial investment. “All of the funds are split up to all these different areas, but the funds don’t seem to make it to none of these different areas [of Englewood], really,” said Joseph Williams, a West Englewood resident and candidate for 15th Ward alderman.

In fact, according to a Weekly analysis of 2017 and 2018 “menu money” that aldermen can distribute for infrastructure repairs and improvements throughout their ward, the money apportioned to Englewood projects was generally proportional to the percentage of the ward that is in Englewood. In some wards, Englewood even saw a larger amount of menu money than might be expected given its geographical share of the ward. That the opposite perception exists suggests both that aldermen aren’t doing enough to make Englewood residents feel well-served and that the share of menu money doesn’t show the whole picture.

The piecemeal development throughout the neighborhood—despite the existence of the 2016 Englewood Quality-of-Life Plan, which all five aldermanic offices worked on—contributes to feelings of neglect. In addition to the Norfolk Southern expansion, many residents and candidates have expressed concern over the other heavy industry making its way to eastern parts of the neighborhood. Recently, Mayor Rahm Emanuel maneuvered the headquarters of the city’s Department of Fleet and Facility Management to a site at 69th Street and Wentworth Avenue formerly occupied by Kennedy-King College. The headquarters will also include a maintenance and repair shop for the city’s large trucks, including fire and garbage trucks. Though Emanuel has pitched the project as an engine for economic development in Englewood, it only shifts existing city jobs from the North Side to the South Side, and a retail component across the street that was teased in 2017 has yet to move forward.

The project is part of Emanuel’s broader plan to build the $95 million police academy in West Garfield Park: the Fleet and Facility management headquarters formerly sat on a parcel of land on the North Side, which the city sold to developer Sterling Bay to raise funds for the academy. Sterling Bay plans to build the controversial Lincoln Yards development on that site. The developer has also bought several vacant city lots along Wentworth in Englewood. (A spokesperson for Sterling Bay refused to comment on what the current stage of the plans are, and didn’t respond to follow-up questions regarding whether or not the developer is still working on the site.)

The old Kennedy-King site was the “only prime real estate” in the 6th Ward for economic development, said pastor and former police officer Richard Wooten, who is running against 6th Ward Alderman Roderick Sawyer. With the current plan, which is supported by Sawyer, “we didn’t get…new jobs. What we got was the pollution of Fleet Management being shifted from the North Side to the South Side,” he said.

“You got the expansion of Norfolk Southern, you got more particles in the air, then you’re adding these major trucks on our road,” said Nicole Johnson, a former CPS teacher and communications manager for Teamwork Englewood—and the only Englewood-based candidate running to represent the 20th Ward—in an interview. “How does that then affect not just our air quality, but our soil and our water? What remediation strategies are going to be employed when you have all these big trucks coming through?” The site of the new mega-high school being built to replace the four Englewood high schools that were closed by CPS last year, as well as an elementary school, are directly next to the Fleet and Facility Management site, separated only by low Metra tracks. “We still don’t know what the effects will be,” added Johnson.

Alderman Sawyer’s support was crucial for the success of both the new Englewood high school and its neighboring Fleet and Facility Management headquarters. By extension that means he also enabled Emanuel’s plan to close four high schools in Englewood and to build the police academy in West Garfield Park, the latter of which he also supported directly with a vote. Sawyer did not respond to a request for an interview.

Pushing back slightly against criticisms of the Fleet and Facility Management project, Butler framed it in stark terms. “Our misfortune in Englewood is that we have vacant sites that sit for decades…. Until we can have consistent development, it’s really difficult to have opinions about any projects, because there’s not many here. Most people are like, finally, they’re [building] on the old Kennedy-King [site].”

Near the intersection of 63rd and Halsted, Foulkes has been building off of the progress made with the TIF-supported Englewood Square mall, which is home to a Whole Foods, Starbucks, and Chipotle. The second phase of the project is gaining momentum, with a data center and a hydroponic urban farming startup co-founded by Elon Musk’s brother both in talks to bring their businesses to strips of city land immediately north and west of the mall. A microbrewery is opening across the street. And immediately north, eighty units of mixed-income housing (including some CHA units) are being developed, as well as two affordable senior housing complexes within a few blocks.

This constitutes much of the new housing being built in Englewood, which suffers from chronic vacant buildings and lots throughout, many of which are owned by banks that would rather let them sit abandoned than pay property taxes. Foulkes said that she has proposed transit-oriented development around the 63rd and Ashland Green Line stop to Emanuel, who she said was impressed (she jokingly accused him of using her plan for the redevelopment of 63rd and Cottage Grove in Woodlawn), but progress on that has been slow.

At the same time, this spate of development, as well as the planned Englewood Line trail, has sparked fears of displacement; 20th Ward candidate Jeanette Taylor, an education organizer, said that residents told her they felt the new Englewood Square is “not for them.” Geographically, Englewood is well-situated for gentrification, since it’s connected to the city center by transit, with multiple commercial districts and lots of land for development. Additional factors like population decline, a mayor seemingly disinterested in the neighborhood unless it serves as a conduit for his larger schemes, a disenfranchised electorate, and a wildly split representative body on City Council portend a neighborhood vulnerable to displacement.

In all of the races for Englewood’s aldermanic seats except the 16th Ward, most of the major talking points have not been Englewood issues. The wide-open race to replace Cochran, a Woodlawn resident, has nine candidates, and five of them are from Woodlawn (the rest are split between Englewood, Back of the Yards, and Washington Park). Nearly all of the myriad forums held, including one co-hosted by the Weekly, have been in Woodlawn, with only one (that the Weekly could find) in Englewood. And though, geographically, more of the ward is taken up by the three other neighborhoods, Woodlawn delivers most of its votes. Accordingly, the major issue of the race—the Obama Presidential Center and its impacts, positive and negative—is not particularly likely to engage the Englewood voters in the ward.

To Johnson, whose campaign office is in Englewood, the ward’s dependency on the Woodlawn vote has posed a tricky balancing act. “The goal is to get people out to vote who have not been touched”—like those in Englewood, she said. But, given relatively limited campaign resources, she said, “it’s a very fine formula that you have to put together in order to make sure that you get the people that always come out, and also reach out to the people that historically don’t come out. They’re both the same people; they just want to be heard, and one of them hasn’t.”

The 15th Ward race, which grew more contentious by the day, became largely focused on Lopez and his perceived unpopularity in the ward, due in large part to his divisive public comments and social media posts about alleged gang members—but also his close ties to political mentor 14th Ward Alderman Ed Burke, his support for the new police academy, and his acceptance of donations from a company that runs private detention centers for ICE.

Over a series of forums in Back of the Yards, Brighton Park, and Englewood, none of which Lopez attended, the four challengers provided more or less a united front against him, declining to run against each other. All of them work in anti-violence—Rafael Yañez was a crime prevention specialist with the CPD before retiring this year, Berto Aguayo co-founded the Resurrection Project’s #IncreaseThePeace initiative, Joseph Williams is a former violence interrupter with Cure Violence, and Otis Davis Jr. is a minister and activist—and have similar platforms.

At the same time, young grassroots organizers, under the banner ¡Fuera Lopez!, have been demonstrating against the alderman, culminating in a protest outside his Brighton Park ward office the day before the election as part of the City Council Cleanup campaign.

The 15th Ward’s shape is especially twisted; it covers a chunk of largely Black West Englewood, but the majority of people in the ward are Latinx residents of Back of the Yards, Brighton Park, and Gage Park. The ward’s power base, therefore, tends to rest outside of West Englewood. (A study of the 2011 remap by two professors at the Illinois Institute of Technology found that the new 15th Ward map, which transformed the ward from mostly Black to mostly Latinx, was the result of punitive “factional gerrymandering” that might violate tenets of the Voting Rights Act.) This year, of the five candidates, only Williams is a West Englewood resident. Lopez previously ran against Foulkes when she was 15th Ward alderman in 2011, before the ward map was redrawn for the 2015 elections.

However, some aldermanic candidates and community groups see a silver lining in the the 15th Ward’s position. “The 15th Ward is one of the few wards where we have the potential to build racial unity, Black and brown specifically, because of the demographics,” said Yañez. Similarly, Voices of West Englewood co-founder Gloria Williams said she has good relationships with community leaders across the ward, and doesn’t see Englewood’s gerrymandering as a problem for her work. “I have a great relationship with the Hispanic community. I don’t see no difference because everybody has to live,” she said.

“I feel like we go through the same struggles. They may be going through ICE, we may be going through the Chicago police up here. And that’s why I hate the fact that it’s really segregated the way it is because when you really look at it, we all are facing the same exact issues,” said Williams. “A mental facility closed down in the Back of the Yards, a mental facility closed over here in West Englewood. So when you look at it, we’re almost living the exact same life.”

Yet Lopez has been criticized for contributing to divisiveness instead of unity. “We have an alderman who divides our community,” said Yañez, the candidate with the most money and endorsements after Lopez. Yañez alleges that Lopez pits neighborhoods in the ward against one another: “[He] goes to one side of it a community and tells them one thing about, for example, West Englewood. He goes to another part of the community and tells them one thing about Brighton Park.” An anonymous flyer posted in West Englewood said that more demolition permits have been issued in that neighborhood on Lopez’s watch than anywhere else. (Logan Square has topped the list for demolition permits in recent years, but West Englewood had the city’s most residential demolitions in 2016, while only two permits for construction were issued, according to Crain’s.) Lopez did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this story, but he has said on Twitter that his “leadership transcends race or geographic politics, brought the entire ward together, and addressed decades-old neglect in ways nobody imagined possible.”

Lopez does have two offices, one in West Englewood and one in his home neighborhood Brighton Park. In 2015, Lopez opened the West Englewood office in a building owned by the domestic violence shelter Clara’s House and then failed to pay months of rent. Lopez’s opponents say this contributed to the shelter’s closure. (Lopez denies wrongdoing, according to DNAinfo’s 2017 coverage of the dispute.) He won the West Englewood section of the ward handily in 2015, but a challenger from that part of the ward (Williams) and the growing progressive critiques of his record could affect his totals there this year.

The relatively low-key races in the 6th and 17th Wards are also focused outside of Englewood. Incumbent Alderman Roderick Sawyer and challengers Richard Wooten and Deborah Foster-Bonner are all residents of the greater Chatham area; Wooten and Foster-Bonner are in leadership roles at nonprofits the Greater Chatham Alliance and Reunite Chatham, respectively, though Wooten is an Englewood native and worked in the CPD’s Englewood district for a decade. He said that the area’s fragmentation has contributed to its decline. (The 6th Ward has historically been centered in Chatham.) In the 17th Ward, one-term incumbent Alderman David Moore faces Rush University Hospital employee Raynetta Greenleaf, an activist in Auburn Gresham, who, despite support from the Teamsters, has raised little money to challenge him with. Moore, for his part, said in an interview that he works well with Foulkes and Sawyer to represent Englewood, and that he’s worked with Lopez on school advocacy.

More than half the 16th Ward is in Englewood—it’s the only ward for which that’s the case—and all of its candidates for alderman are residents of the neighborhood. The race has centered around accusations that Foulkes is absent, and that her lead challenger Stephanie Coleman is simply an example of Chicago political nepotism; she is the daughter of former Alderman Shirley Coleman, who represented the ward from 1991 to 2007. Coleman forced Foulkes into a runoff last election and beat her in the Democratic ward committeeman race a year later. She has received considerable support from establishment politicians, including Governor J.B. Pritzker, 34th Ward Alderman Carrie Austin, and state Senator Tony Muñoz, as well as developers, charter school boosters, and TV personality and former Detroit judge Greg Mathis.

The Weekly attempted to schedule an interview with Coleman before the election without success, but she said at a candidate forum in Englewood last month that she will be a fighter for the ward—implying in the process that Foulkes is not. (Foulkes did not attend the forum.) Eddie Johnson III, a CPS educator, went further in an interview, criticizing Foulkes for her fifty-seven percent attendance rate at City Council committee meetings, which WBEZ reported this month. Possibly in response, Foulkes’s campaign recently released a map of the projects she has completed in her last term, or that are underway. She said in an interview that the projects amount to about $175 million in economic development. When asked about Coleman’s political supporters, most of whom have few ties to Englewood, she asked, “What is their interest? Because Englewood is hot, and it’s a lot of money to be made.”

Multiple candidates—including Williams, 20th Ward candidates Jennifer Maddox and Nicole Johnson, and 16th Ward candidate Eddie Johnson III—have suggested that one solution to solve the fragmentation, at least before a new ward map can be negotiated, is to create an informal council of Englewood aldermen. “I want to find ways that we can collaborate on smaller projects—start small, and build that trust, because that’s what the issue is,” Nicole Johnson said. “There’s a lack of trust between colleagues and what people’s intentions are, and who’s going to get credit for it. And you know, that’s the name of the game here. Politics is, let me make sure my name is on it.” She suggested going even further, proposing that certain grant or tax monies be only made available to aldermen who regionally plan within the city with their neighboring wards.

And all of the candidates have their eyes on the 2020 remap. Conscious of the decreasing population, and wary of the gerrymandering that has preceded them, most interviewed said that the redrawing process in 2011 hurt residents, who were, in Foulkes’s description, “bamboozled.”

“We need to change the formula being used,” Foster-Bonner, a Chatham resident, said. “There’s no reason why I’m here representing almost a third of the ward.… I don’t know [other parts]. I’m trying to get to know [them],” adding that she would have two offices in the ward: one in Chatham and the other in Englewood. Aguayo is canvassing with University of Chicago sociologist Rob Vargas, who studies how gerrymandering increases violence. “We’re having these conversations about what would it look like to have a truly equitable map in this part of the city of Chicago,” he said, saying he hears from many residents of his home neighborhood of Back of the Yards that they are similarly frustrated at being divided into five wards.

Richard Wooten summed up the urgency of the remap: “We have to have people in position right now talking about how they want Englewood to look in the political arena, because if you’re not talking about it now, you’ve already lost.”

Christian Belanger, Joshua Falk, Ian Hodgson, Sam Joyce, Samantha Smylie, and Yao Xen Tan contributed reporting

Mari Cohen is the Weekly’s workshop manager and a senior editor. Sam Stecklow is a managing editor of the Weekly and a journalist with the Invisible Institute.

WOW I have a headache