Last week, the Institute for Housing Studies (IHS) at DePaul University released its newest annual report on the state of rental housing in Cook County. While the report shows small changes within individual neighborhoods, the overall trends across the county are largely unchanged from previous years: less traditionally affordable housing, high levels of cost-burdened tenants, and a large gap between the supply and demand of affordable housing.

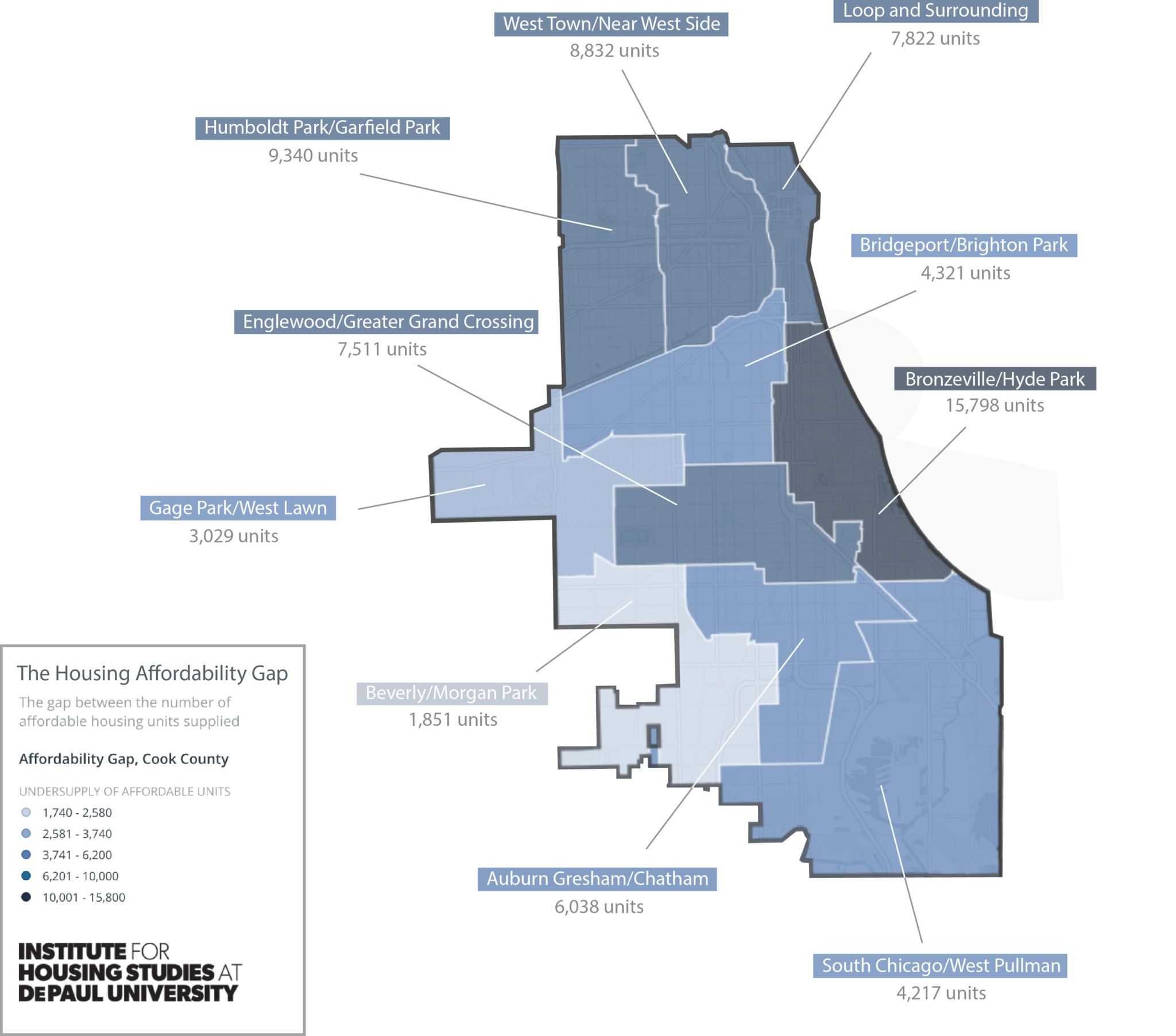

The last number is perhaps the most immediately jarring. Across Cook County, the affordability gap in 2016 was around 182,000 units; while down by 6,000 units from the year before, that’s up from 157,000 in 2007. The affordability gap, as the IHS defines it, is the difference between the number of low-income households that earn 150 percent of the poverty-level income (the demand for affordable housing) and the number of rental units available to one of those households at thirty percent of their monthly income (the supply). (The calculation also includes households that earn above 150 percent of the poverty-level income but are occupying one of the affordable units, since they affect the supply level.)

The report also finds that this gap is largest on much of the mid-South Side, in the area made up primarily of Hyde Park, Kenwood, Bronzeville, Woodlawn, and Washington Park. There, the affordability gap in 2016 was around 15,800 units. Though that is 1,400 more units than in 2015, Geoff Smith, executive director of IHS, cautioned against drawing out too much significance from year-to-year comparisons, since the IHS analysis stretches back over multiple years. He did note one possible reason for the increase, though: “Along the south lakefront there have been population increases in places like Woodlawn and Washington Park. I think some of that population increase has been lower-income households who would be in that demand component for affordable housing.” (Note that the data the report uses only measures through the end of 2016—that means sudden, recent trends, such as a hotter real estate market in Woodlawn, won’t necessarily show up in full for another year or two.)

Worryingly, the report also shows that the stock of two-to four-unit buildings across the city continues to remain below its historical level. That’s important because two-to-fours, as they’re commonly called, have long been an important source of affordable housing in the city. But after the financial crisis, foreclosures of two-to-fours in neighborhoods on the South and West Sides increased dramatically. For example, a 2012 report from IHS showed that forty-three percent of Englewood’s two-to-four unit buildings went into foreclosure from 2005 to 2011. That was the highest share of foreclosures in the city, but statistics from other South Side neighborhoods are almost as jarring: forty percent in Burnside, forty-one percent in Washington Park and Woodlawn.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Things have hardly gotten better in the half-decade since then. In 2016, 30.8 percent of the rental supply was in two-to-four unit buildings; compare that to 35.7 percent in 2007. And the loss of those buildings is bad news for lower-income renters. “The reason that we’re focused on two-to-four housing stock is because most people who are trying to find affordable housing don’t really get it from subsidized buildings,” said Smith. “Replacements for those units are probably going to be expensive. Most new developments are oriented toward higher-income renters.”

The loss of traditionally affordable housing stock goes hand in hand with another continuing trend: the high percentage of rent-burdened households in Cook County. Any household that pays more than thirty percent of its income in rent is defined as rent-burdened, while those who pay more than half their income are severely rent-burdened. In 2016, 87.5 percent of households that made less than thirty percent of the area median income in Cook County (about $77,000) were rent-burdened, and seventy-four percent were extremely rent-burdened. In other words, a large majority of the poorest households in the city and suburbs are facing a continuous, monthly affordability crisis.

To solve these problems, IHS recommends a nuanced approach that differentiates between the needs of different neighborhoods. In gentrifying areas, for instance, Smith suggests that nonprofits and the city focus on maintaining existing affordable housing, while more affordable housing should be built in already-rich neighborhoods that lack it. Lower-income areas, meanwhile, don’t tend to suffer from a lack of affordable housing; rather, residents’ incomes are often too low to afford any sort of housing without shouldering undue costs. “The problem is that incomes for folks in those neighborhoods are so low that any housing isn’t affordable,” said Smith, nothing that IHS wants to focus on “getting investment to improve existing housing stock, while also providing some rent support for tenants in the neighborhood.”

What about taking Lawndale (north & south) as a separate area into consideration?

Hi Dolores—the areas outlined on the map are Public Use Microdata Areas that are determined by the U.S. Census Bureau, and is how the data that the Institute for Housing Studies used was broken down. You can read more about their methodology here.

— Sam Stecklow, Managing Editor