When Illinois House Bill 5530 was passed in July 2016 and became a Public Act, many educators and cafeteria workers were unaware that excess cafeteria food could legally be donated to food pantries and homeless shelters.

The bill—which forbids public entities from joining into food service contracts that prohibit donations of leftover foods—was promoted and supported by a number of regional organizations, including Seven Generations Ahead, the Illinois Scrap Food Coalition, and SCARCE (School and Community Assistance for Recycling and Composting Education).

While the bill technically did not change schools’ ability to donate their leftover food, the organizations behind the bill are hoping that it will contribute to their efforts to help schools reduce food waste, by donating leftover foods, composting, and recycling.

A lot of food goes to waste in the Chicago Public School system.

According to a survey conducted during the 2014–2015 school year by Seven Generations Ahead (SGA), an environmental nonprofit based in Oak Park, fourteen Chicago public schools were throwing away approximately 3,577 pounds of food per day—much of which could have been either donated or composted.

“A key component of zero waste is reducing waste in the first place,” said Jennifer Nelson, SGA’s Program Manager. “The bill supports recovering food that can be eaten before looking to compost or dispose of what cannot be eaten.”

Looking to divert wasted school food from the landfill, SGA created a Zero Waste Program in 2007. They worked primarily with schools in the Oak Park and River Forest areas to improve recycling and to compost food scraps.

According to Nelson, people are excited to learn about sustainability but might not know where or how to get started. “We really believe that educating students to understand their role in making sustainable choices is really critical, so we’ve worked with schools from when the organization was founded through now. They’re excited to know that they can choose to make a decision that is going to be environmentally sound, and they take the message home,” Nelson said.

Eric Solorio Academy High School in Gage Park is one of the schools now involved in the program. Greta Kringle, a science teacher and Service Learning Coach at Solorio, reached out to SGA over the summer of 2015 after hearing about the organization through WBEZ.

“I had been doing a unit in my chemistry classes about conservation of mass and chemical reactions that happen with our waste after it leaves our homes, and I often had students asking me why we weren’t doing more at Solorio to solve the waste problem in our society,” said Kringle.

The school then got involved with SGA during the 2015–2016 school year, in January, after her students expressed enthusiasm at the thought of implementing SGA’s Zero Waste Program..

Susan Casey, SGA’s Zero Waste Schools Project Manager, says that not every school is on the same level when it comes to composting and recycling methods, so SGA meets the schools where they’re at.

“If they haven’t started recycling, we start with that. Some schools have the option for composting, or even doing on-site composting. [We] help them think of options for waste reduction as well,” said Casey. The organization assembles a zero waste team comprised of teachers, administration, custodial staff, kitchen staff, and students, and they work together to figure out what will work best, school by school.

“It varies depending on which strategies are used but in the schools that have commercial composting—because of the density of food scraps, it’s a really significant diversion by food waste.”

Casey says that SGA is seeing “a total diversion from the landfills in the range of eighty to eighty-five percent from schools that implement commercial composting, recycling and liquid diversion—which just means students empty out their milk cartons before they recycle them.”

In 2014, CPS partnered with SGA and its hauler, Lakeshore Recycling Systems, to create a Commercial Composting Pilot Program. Their goal was to educate students, staff, and families about the importance of recycling, composting, and food waste reduction, to determine the best practices for CPS as they look to expand the program district-wide, and to divert eighty percent of all cafeteria and kitchen waste from landfills through recycling, composting, and food sharing and recovery.

SGA found that the fourteen schools enrolled in the program as of November 2017 reduced their food waste percentage from seventy-eight percent to eighteen percent. Food sharing—when schools take items that students have not eaten to shelters or pantries—increased from fifty-six pounds per day to 232 pounds.

SGA’s efforts to reduce food waste in Chicagoland schools are ongoing. They plan to implement more food-saving strategies in the future. The Illinois Food Scrap Coalition, of which SGA is a member, headed the Food Scrap Composting Challenges and Solutions in Illinois Project, the final report for which was published in January 2015. The report examined opportunities to reduce food waste through food donation and composting, as well as identified challenges surrounding the transportation of food between public entities and food pantries and shelters.

“Often there are challenges around transporting the donated food, having an unpredictable amount and type of food, and having limited days when the recipient agency can accept and distribute food,” said Nelson.

As they prepare to help schools ramp up their food donations, especially after the passage of Bill 5530, organizations like SGA and SCARCE are working to incorporate children, parents, teachers, and staff into the waste reduction process.

SCARCE, a nonprofit based in DuPage County, has been working for the last twenty-five years to create sustainable communities through hands-on programs and activities, like composting education.

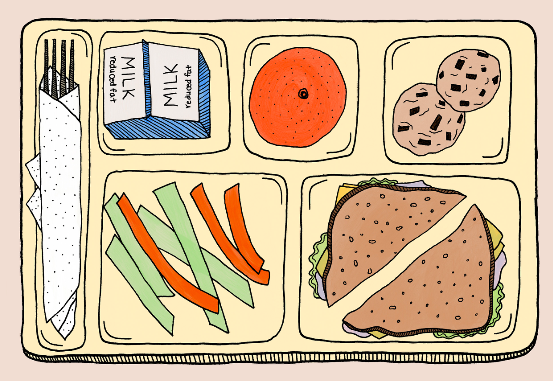

Like SGA, SCARCE also conducts waste audits in school lunchrooms. “Our biggest lunch [audit] that we did had eighty-one sandwiches thrown out without a bite,” said Kay McKeen, SCARCE’s founder and executive director.

The audits are key to establishing a roadmap for instituting food diversion practices and to soliciting interest, and ideas, from students.

“When we do our waste audits, we measure food that could be donated,” Nelson said. “Some schools have programs in place to donate and others have not yet established such a program.”

Through waste audits, SGA helps the students and teachers sort the garbage into resources. For example, they take out the items that are recyclable, like milk cartons, straw wrappers, and brown paper bags and separate them from the items that are made from petroleum: plastic bags, plastic bottles, plastic lids, and silverware. Then they sort the food. The waste audits give the students an idea as to how much food is being wasted—and spur them to come up with solutions to the problem.

“One of the things we’ve done is encourage schools to put this in the hands of the students,” said Nelson. “To have what we call Zero Waste Ambassadors who receive a little more training and it becomes a leadership role for them.”

Encouraging the students to take the lead with this project gives them an opportunity to learn about recycling and composting while engaging others in conversation about waste reduction.

At Solorio, kids are leading the way in measuring the foods that leave their cafeteria. “The students in my chemistry class measured the mass going to the landfill each day in our cafeteria and it was around 480 pounds during our lunch periods every single day,” said Kringle.

The program has helped students at Solorio Academy see food waste from a new perspective, and some of the students have even started implementing these efforts at home.

Many students “have expressed to me that they have improved their home recycling, and I have even had a few go home and start backyard composting,” Kringle said “I think the biggest take-home for many of them is just seeing waste in a new light. They start thinking about what they are throwing away and making decisions that end up reducing the waste they generate individually.”

“We still have a long way to go in terms of making Solorio a truly zero-waste facility, but the program has started the conversation and changed the habits and mentalities of students and staff,” Kringle added. “It is a lot of effort, but I think the lessons that are learned are worth it.”

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly