When professional photographers Becca and Mik Major moved into their Kenwood condo at 50th Street and Dorchester Avenue two years ago, the real estate agent told them they were following in distinguished footsteps: another photographer, Nancy Hays, had lived there before them. Up until her death in 2007, Hays had been an active community presence in Hyde Park as both a longtime news photographer for the Hyde Park Herald, and a fervent conservationist.

Intrigued, the couple contacted the Hyde Park Historical Society, and learned that Hays had willed 167 boxes of film, negatives, correspondence, pamphlets, and other materials to the group; all of it was sitting, largely unexamined, in the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library. “When we went to the library, we found a box that had four binders of negatives in it… and then we took them home and probably had them for about a year,” said Becca Major. Once the Majors got around to looking through them, the photos in the box came to serve as the basis for “Nancy Hays: A Retrospective,” an exhibition in the Historical Society’s headquarters at 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue that opened in late October.

The show includes twenty-three black-and-white photos taken between 1987 and 1992, culled by the Majors from what they estimate were about 24,000 negatives. (To speed up the selection process, the couple scanned many of the prints using their iPhone’s negative mode, which shows the image as if it were developed.)

The full context of some of the pictures has been lost: Hays would annotate her files with short descriptions (“Toni Preckwinkle” or “IC embankment”) that don’t always describe, or do justice to, the photos contained within. One image, of a girl jumping rope, is from a set enigmatically labeled “Concrete Repairs.” Michal Safar, the president of the Historical Society, said she thinks it was taken at the Burnham Park fieldhouse down by the Point, but can’t be sure.

Several other photos allow for similar detective work. In one, a woman helps a kid, oversized naval cap firmly bucketing half his head, climb a tree. It’s the kind of image—she seems patiently exasperated, he’s mildly apprehensive—found in family albums and nature documentaries everywhere. But certain out-of-focus buildings in the background also reveal more concrete details about when the picture was taken: looking past the water, you can see the Flamingo Apartments and a taller beige building on South Shore Drive, but the Montgomery Place nursing home, built in 1990, is absent. The 167 boxes sitting in the Regenstein probably map similar changes to a little area of Chicago over many decades, the obvious yet unobtrusive shifts taking place behind the people playing chess at Harper Court or sunning themselves on limestone by the lake.

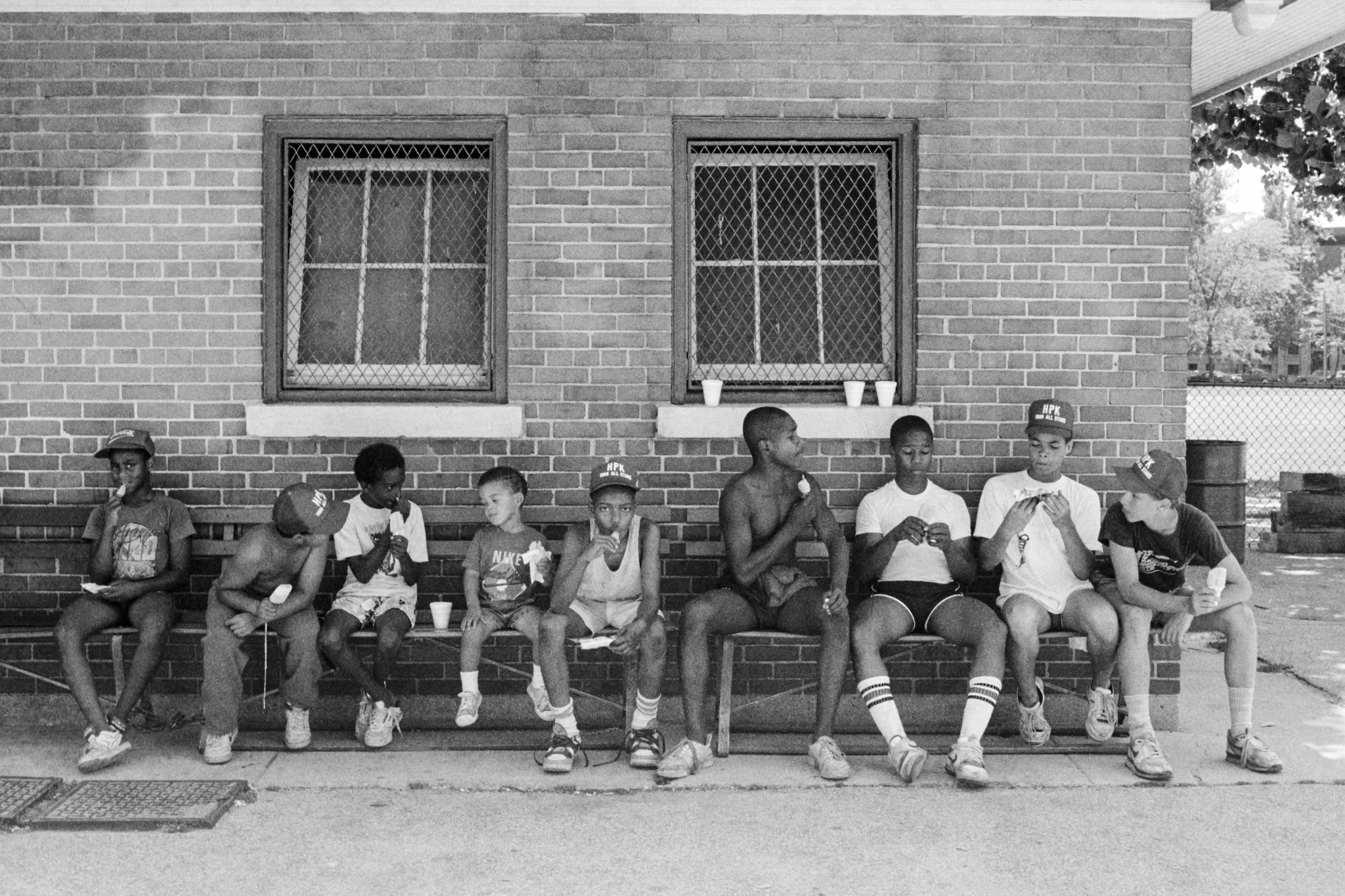

Many of the other photographs in the retrospective also feature children: a row of Little League players eating ice cream, two kids sitting on a skateboard while watching construction workers dig up the sidewalk, a pool teeming with junior-age swimmers, a now-demolished church in the background. Children were a lifelong subject for Hays: one of the only exhibitions of her photographs put on during her lifetime, “The Ingenious Child,” was an exploration of children at play in Hyde Park during urban renewal. “You could tell she was a street photographer interested in people and lifestyles and moments, and she was really good at children,” said Becca Major.

As part of her conservation work, Hays helped found the nonprofit Friends of the Parks and served as president of the Jackson Park Advisory Council; in the sixties, she was arrested for protesting Mayor Richard J. Daley’s plan to cut down trees to widen Lake Shore Drive. Her love of public parkland is also on display in the retrospective, albeit more subtly. Photos taken around Jackson Park, and particularly at the Point, demonstrate an eye for the possibilities of shared space, and the various ways people put it to good use. A woman holds a cardboard protest sign that says, “Independence? Freedom? What About For Women? Keep Abortion Safe, Legal, + Funded.” A couple of horseback riders in spurs and straw hats, the Black cowboys that still congregate for an annual picnic in Washington Park, trot through the grass. There’s also the more everyday—a family reunion, bicyclists, basketball players.

“She was exploring the relationships between people and their land and their communities,” said Becca Major. “I think this was a really powerful statement when she was making it and seems really powerful now.”

Hays was born in Ann Arbor and got her start in New York, but moved to Hyde Park in her thirties. The forty-nine years she lived in the neighborhood ended up yielding, Safar estimates, hundreds of thousands of photos, some of them printed in the Herald and other outlets, but many of them only available in Special Collections. Safar hopes the Historical Society can start seeking grants and fundraising to pay for the boxes to be examined and catalogued by archivists. (The organization raised $7,000 to put on the retrospective.) She also hopes the current exhibition can be shown at other venues around the city.

The Majors, for their part, plan to remain involved. “It’s very much a passion project… We knew that we were gonna be volunteering our time, but were gonna be inspired by what we found,” said Becca Major. “It was great how observant she was to her space and community and other people. She had opinions and made them known, and I think that’s important.”

Nancy Hays: A Retrospective, Hyde Park Historical Society, 5529 S. Lake Park Ave. Historical Society building open January 26, 2pm–4pm and February 1, 2020, 2pm–4pm. Check website for other times. hydeparkhistory.org

Christian Belanger is a senior editor at the Weekly. He last wrote about a biography of Nelson Algren.