Artist Raub Welch was gardening at his home in Bronzeville when a child approached his fence, asking for money to buy a pair of shoes. Welch, who recently moved from the North Side, was ready with a response. “I had my game face on,” he remarked. Assuming the child was trying to hustle him, Welch refused.

He was subsequently astounded to learn that the child had no father. “That’s not possible,” Welch thought to himself. “I started developing scenarios of why this kid didn’t have a father.” And so his most recent art exhibit began to take shape.

Welch recounted this jarring experience in a conversation with Madeline Murphy Rabb at the DuSable Museum, where his exhibit, “The Endangered Species: A Visual Response to the Vanishing Black Man,” is currently on display. A mostly black audience sat in narrow rows of folding chairs in the negative space between DuSable’s galleries.

Welch is black, but he feels himself to be something of an outsider. As he went on to explain, he grew up on a 960-acre farm in southern Illinois, far removed from the experience of urban racial identity that confronted him upon moving to Bronzeville with his family. “I didn’t understand that blackness,” Welch observed. “I was a farm kid.”

“The Endangered Species” envisions a future in which the black male is extinct and white viewers have come to see an archaeological reconstruction of what he once was. Welch’s works surge beyond this imaginative premise to present pressing questions about the current state of African-American manhood, exploring themes of identity, masculinity, oppression, responsibility, and the frustration of hope.

In one of the pieces, four typewriters present pieces of paper, each printed with a word: “negro,” “colored,” “black,” and “African-American.” The first three words are crossed out in red ink, while the final one bears a question mark. Welch explained that it represents the attitude that “we’re just not the right type.” He elaborated, “We’re always searching for something, something that will give us power.”

He was not afraid to be critical, and blunt. Of the black male, he remarked, “This is a beautiful body. This is a beautiful person. Why is it demonized to the point that I start to hate it?”

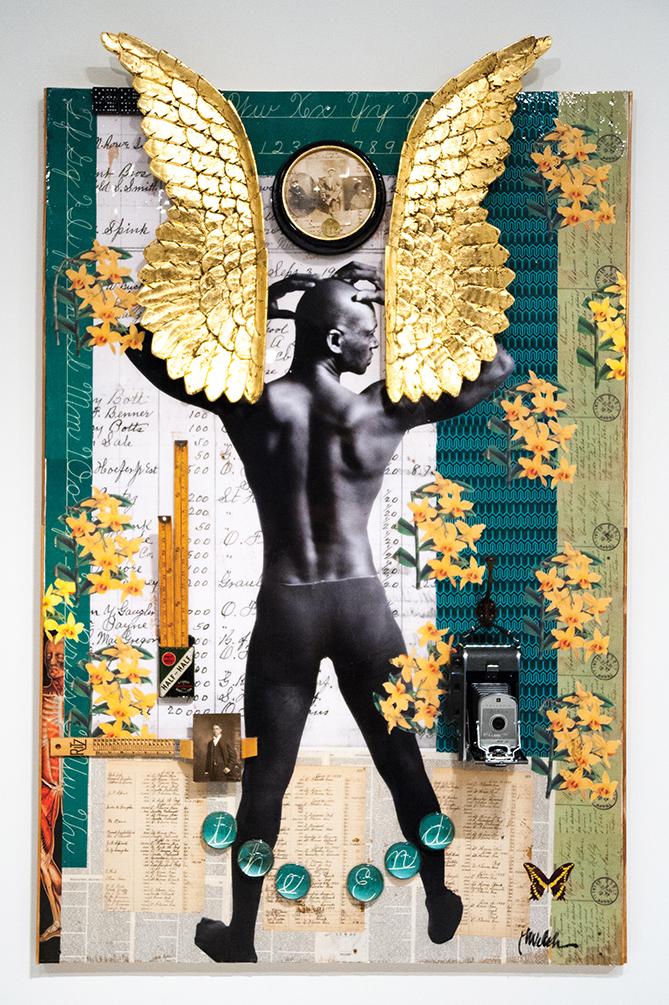

Welch’s art demands that the viewer critically examine aspects of black male identity—love, religion, consumption, vanity. In one prominent section of the exhibit, resin-coated canvasses depicted black male models stripped to their underwear, each one drawn into three-dimensional collages with found objects from Welch’s extensive collections.

Objects stand on their own in other works, such as “The Golden Imitation of the Parade of Spades.” This piece, composed of found letters rendered precious by gold leafing, highlights the innovative capabilities of black people throughout history. “Black just comes with innovation. You’re given the worst of every situation,” Welch explained. “We’ve always had to do this.”

Welch’s art expresses sympathy toward the plights of the black man, while at the same time presenting an urgent criticism and warning. One of the centerpieces of the exhibit, a work entitled “The Evolution of a Slave,” occupies the rear wall of the gallery space with four panels depicting the evolution of a black man from slavery to the modern day. In the final panel, the recurring male figure casts his head down in a distressing depiction of retreat towards the primal state in which he began. According to Welch, “It embodies everything that I think is happening to our race right now.”

“I’m very candid,” he cautioned the audience, as he spoke about his experiences of frustration with the black community. “We’re the only people in the world that, when you get something nice, someone says you’re trying to be someone else,” Welch lamented. The audience murmured in agreement.

His disparaging remarks about the north-south divide in Chicago proved more contentious. “I have very negative images of the South Side,” Welch said sadly, but not apologetically. “I feel like the air is even better on the North Side. I feel like the trees are even greener.”

Welch’s recent effort to line his street in Bronzeville with trees floundered, because a neighbor feared the trees would harbor drug dealers.

Nevertheless, he showed hints of hope. As he said of his show: “At the end of the day, it’s a call for us to save ourselves.”